The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Hunting

Hunting  African Big Game Hunting

African Big Game Hunting  Stories: Guardian of the Ruins; The Baboon Feast; The Shangaan Song

Stories: Guardian of the Ruins; The Baboon Feast; The Shangaan SongGo  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| One of Us |

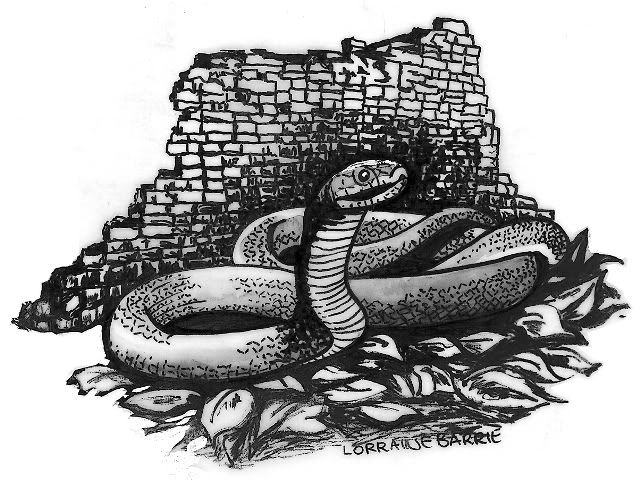

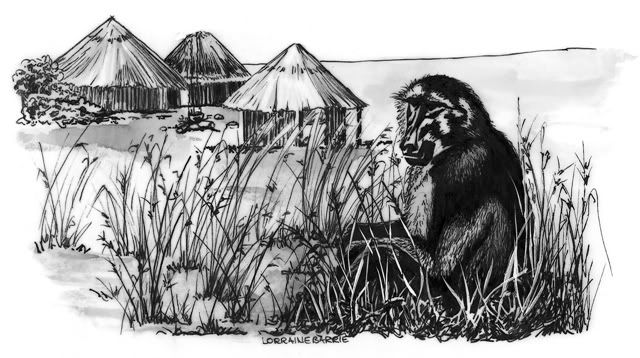

Hello I hope you are all having a good weekend. These stories are chosen randomly from my book 'The Shangaan Song', which is a collection of tales from the bush. The first three stories are from Ruware, an awesome chunk of Zimbabwe's lowveld where I grew up, and the next three are from the Zambezi Valley. The book comprises 24 stories in total. Incidentally, Pencil was an old Shangaan lion hunter who began working for my great uncle Ian de la Rue in 1936. Pencil doesn't feature so much in the stories I have selected to post, but the book was actually inspired by him and dedicated to him. Between 1940 and the mid 1970's, Pencil Chekenyere, a man short in stature but huge in soul, shot approximately 300 cattle killing lions. I hope the stories don't bore you too much! Nice sketches anyhow. Look out for the photos of the maneater of the Nyaodza, at the bottom of the story, in the next post. [URL=  ][IMG] ][IMG]GUARDIAN OF THE RUINS Dad and I are taking an afternoon drive down to the Chiredzi River, to ‘see what we see’. It is hot and I am hanging my head from the window in search of wind relief. The Land Rover growls its way over the rough track, occasionally encountering and negotiating steep, rocky waterways. Ever downward we go, gradually dropping into the Chiredzi River Valley. In time we pass by an elongated, low-lying kopje, not far off the road, on my side. Kopjes mean several things including klipspringers, appealing little kopje dwelling buck and one of my favourite animals. With klipspringers in mind, I scan the muddled rock collection through the lightly wooded demarcation as we cruise slowly by. Suddenly I spy irregularity. Actually it is regularity that I spy, but that is irregular in this setting of natural non-conformity. “Stop Dad,†I say, and he dutifully does. “I saw something back there in the kopje, something unusual, part of a wall?†I look enquiringly to Dad. “Yes,†says Father “there are ruins in that kopje, I’ve been told about them.†We reverse a short distance back up the road and I soon see the stonework again, more clearly this time, certainly man made and therefore alien in this area devoid of men. “Let’s go and have a closer look,†I suggest, and Dad shakes his head. “Sorry to disappoint you son, but the elders have briefed me about this place. It is forbidden to go there. It’s hallowed ground if you like, only accessible to a very few powerful elders. You and I are certainly not permitted to approach those ruins. Let’s carry on down to the river; we can’t make out much of the ruins from here anyway.†Then and there, I determine that that brief visual of anciently arranged stone would not be my last experience of this place. I am sitting with Pencil outside his hut, brewing tea and hacking chunks of bread with his bush knife. “Mdala,†I say, and he looks up. “Mdala, tell me of the ruins, the ruins down by the river, the ruins which are the forbidden ruins.†Although I feign passing comment and continue preparing the tea, avoiding eye contact, I feel the Old Man’s penetrating gaze. Staring at me intently, he launches into serious speech. It could become disciplinary speech, I sense the possibility in his no nonsense tone. “The ruins down by the river are indeed forbidden, to all men. That place is a place for the spirits and for the spirits alone. No mortal man may approach those ruins without first receiving the blessing of the Great Spirit. Nobody has ventured close to that place for many years and great harm would befall anyone who did. The ruins are the home of the ancestors. Why do you ask about the ruins?†“I had thought of exploring the area, as you know I am most interested in local history.†“You may never, ever explore that area. Anywhere else is possible but not that place. Do you understand?†The Old Man is getting a little worked up because he feels I am going to argue the issue. I don’t, already aware of what the outcome will be. “Yes Sekuru, I understand,†I say, pouring boiling water into two tin mugs. “Do you understand fully?†says the Old Man. “You may never approach those ruins. The consequences of such a foolish action would be dire indeed. There is a monster snake that guards those ruins at all times, a monster flying snake far greater than any snake on earth. The snake is larger and more powerful than a python, faster and more venomous than a mamba. The snake is the spirit of a great Shangaan warrior and it is the guardian of the ruins, as are the bees. You must promise me that you will never approach those ruins. The spirits would be greatly offended and your life would be in grave danger. Promise me.†Meekly, I promise. The Old Man and I sit together outside his hut, sipping strong tea and tearing bread from primitively hacked wedges. It is impossible for me to forget the ruins, although I don’t bring the subject up again for I am busy scheming – scheming and inquisitively daydreaming. Dreaming about what one could possibly find down at the ruins, if one were brave enough to go there. My teenage mind is struggling seriously with the willpower factor, with the willpower factor and the still undefined difference between bravery and stupidity. Anyway, I go to the ruins in secret one day and this is what happens. It is a long walk from Chehondo to the ruins down on the river and, although I leave at dawn, the sun is burning high when I arrive. Sitting down on the road verge close to where Dad and I stopped before, I pull hard on my water bottle and look the controversial kopje over. All is quiet, even the insects stilled by the mid-morning sun. I spend some time there on the road, plucking up courage and trying to convince myself that I cannot allow superstition to dictate to my new age teenage mind. And then I approach the ruins, the home of the spirits where no man may venture. The ruins are interesting indeed; although a couple hundred years of element exposure has taken its toll, much of the structure is still intact, the original architecture easy to envisage and appreciate. As far as ruins go, this is one of the most pristine examples I have so far come across. Added to which there is much broken pottery lying about, and God only knows what else. I quickly become absorbed in exploratory activity, all thoughts of spirits and the forbidden zone having long since evaporated. With enthusiasm, I clamber about, searching for I know not what. Later, I figure I must have spent about half an hour at the ruins, although I cannot be sure. Everything that took place before the snake’s advent became instantly and everlastingly irrelevant. All I shall ever remember clearly of that day was the snake. The largest and most fearsome snake I have ever come across, raising its length from the long grass and towering high above my crouched form, gently rocking, back and forth. I am crouched down, attempting to work a piece of what appears to be metal from firmly encrusted soil entrapment, when I sense something. Glancing up, I look into the most terrifying pair of eyes created by God. The beady, focused eyes of a huge black mamba, towering high above and staring me down. Terror freezes me to the spot and it seems a long time that the mamba and I look each other over. Of course, it can only be seconds. Although I have seldom come across mambas, I am able, like any bush born boy, to easily identify these snakes. And I am fully aware of their deadly reputation. For the first time in my short life I confront certain death, from no more than two metres away. Although there is no definite thought process engaged, instinct fortunately takes over and I begin to move. Naturally my first movement is retreat. Slowly I crab backwards, inch by painstaking inch over the rocky ground, never removing my eyes from the snake, anticipating the strike. And I pray that this serpent notes my humble submission. The mamba continues to gently rock – boring black eyes and slightly gaped black mouth, flickering tongue deciding my fate. Fortunately the terror instiller does not advance and I am able to cling tenaciously to control, barely prevailing over outright panic. Ever so slowly I continue my backward crawl of supplication. Time passes and the neutral ground is gradually increased. When I have reached a point that is obviously a suitable distance from the mamba, it finally accepts my surrender and descends into the grass, making off away from me. And I curl up on the floor, drained by raw terror. A short time later, I run away from the ruins and, although it is a fair distance to Chehondo, run all the way home. Of course, I never tell anyone about my ordeal at the ruins down by the Chiredzi River. It would be an admission not taken lightly by either Dad or Pencil. It is weeks later, just when I am beginning to believe that I have gotten away with the transgression, that the Old Man drops the bomb. We are fishing down at the dam when the brief conversation takes place. From out of nowhere the Old Man stares deep into my soul and makes the statement. “You went to the ruins, the ruins by the river.†A statement not a question. I struggle to engage voice but eventually croak out a ‘yes’. The Old Man’s ancient almond eyes are focused completely on my guiltily darting blue pair. “Look at me and listen to me Dungbeetle,†he says softly, gently reassuring. “I am not angry for you have received your warning. You, and all of us, are most fortunate that the spirits felt mercy and delivered that warning. You must never disobey me again, promise me that.†I have found my voice and I promise the Old Man, this time with inner conviction. I do not ask the Old Man how he came to hear of the incident at the ruins, for I know he has a strong rapport with the spirits. And I do not tell him that the guardian is a mamba, not a giant flying snake larger than a python as he had previously told me. I wonder how it is, that with such a strong spiritual connection, the Old Man could have been so fundamentally wrong when describing to me the guardian of the ruins. [URL=  ][IMG] ][IMG]THE BABOON FEAST There has never been a more humble man than Tiyani the hermit. Soft-spoken and hard working, Tiyani was born on Ruware and has given a lifetime of loyal service to Ian de la Rue, working as a herdsman. Dad has always been full of praise for Tiyani, constantly expounding on the many virtues of that good man. ‘He is an honest and diligent worker, a man to be relied on,’ Dad says. Tiyani lives alone, far removed from anything vaguely resembling civilization. His kreb is situated deep in the bush, not far from the prevalently dry watercourse that is the Benzi (mad) River. This unlikely name was bestowed upon the river many years prior when, after persistent and unexpected flooding, it claimed several lives. These days it is anything but a mad river, the rains having been rather uninspiring of late. Tiyani is not married and he practices a reclusive lifestyle. Bachelor status is not common in rural Zimbabwe and once I dared to ask him why he did not take a wife. Yes, in Africa we take wives. After a short concise monologue during which Tiyani pointedly explained to me the many advantages of bachelor-hood, I went away completely convinced. Like other Shangaans from our area, Tiyani has some extraordinary dietary preferences, baboon meat being one of these. Whilst it may seem a bizarre – and indeed repugnant – custom to most people, baboon eating is a fairly common practice in the Lowveld, a dish enjoyed by many. This practice is not exclusive to black people – certain lowvelders of European origins have also adopted the tradition, partaking in what they assure me (the uninitiated) is a delicacy. Ian de la Rue has eaten baboon on occasion, amongst other strange creatures, and my brother Jonathan eats baboon to this day, amongst other strange creatures. When Jonathan is home, he and I spend much of our time hunting baboons. This activity is one of our favourite pastimes. Having adapted well over the years to the pseudo environment created by cattle ranching and irrigated cropping, baboon numbers have recently reached an all time high. The unwritten policy is to shoot baboons on sight and, as enthusiastic youngsters will, we go about the task with gusto. Although there are many baboons, shooting them is not as easy as one would imagine. They are wily creatures with keen senses, specifically eyesight. Baboon hunting requires dedication and we are often unsuccessful. When we do get lucky, the primate (and possibly mates) is unfailingly delivered to Tiyani. No one else appreciates the treat nearly as much. A mealtime or two after a successful baboon hunt often finds Jonathan dropping in at Tiyani’s house for a bite to eat. Naturally, baboon is always on the menu. Although I steadfastly refuse to eat baboon, I usually go along for the experience, and that it surely is. Preparation of the baboon feast is an important ritual to Tiyani and he would never entrust that duty to any hands other than his own capable pair. Tiyani is a man of enviable culinary talent and he takes great pride in this ability. One of Tiyani’s favourite dishes is baboon hand starter, an appetizer served before the main meal to whet the appetite. He says that the tastiest part of a baboon is the finger and hand flesh. Firstly, and obviously, Tiyani severs the hands from the baboons in question. He then takes his honed skinning knife and carefully skins out each hand up to the finger bases, creating hand pouches. Once this intricate task is complete, he carries out a little de-boning exercise and stuffs the pouches with a few tomato and onion chunks, before tightly tying off and sealing the wrist ends. The hands are then popped into a pot of salted water and left to boil for thirty minutes or so. When cooked to his satisfaction, Tiyani removes the hands and grills them for a couple of minutes either side on hot coals – they are now ready. Each man takes a hand and the feast begins. Witnessing the consumption of baboon hands by Tiyani and Jonathan is not pretty. One by one the fingers are lopped off, and the mushy vegetable and baboon relish is slurped down eager, pulsing throats. The scene is reminiscent of schoolchildren sucking penny-cools dry – there is the same degree of concentration and the same suckling noises. Between hungry slurps the silence is palpable, such is the level of animated absorption. Due to the dedication displayed by the diners, the starter phase never lasts too long. Once the last drops of relish have been wrung out, and the finger bones nibbled clean, the hand remnants are discarded and the main course addressed in earnest, tackled actually. Fortunately the main course is a much tamer affair, usually comprising baboon stew and sadza (maize-meal). Even then it is difficult to remove one’s imagination too far from the scene. Evidence of the baboons’ demise and ingestion is always close at hand, in one form or another! After any given feast, we always rest together beneath the leafy canopy of a giant leadwood tree close to Tiyani’s hut, the two eaters digesting contentedly. This leadwood is Tiyani’s favourite tree and he religiously passes his daily siesta here, sheltering from the burning lowveld sun. Sitting propped against his leadwood tree, snorting copious quantities of snuff and reliving the finer details of yet another tasty feast in satisfied conversation with my brother. That is how I remember Tiyani. It is raining on the day the messenger arrives. Not a typical lowveld thunderstorm, those are reserved for the end of season summer months. No, this is winter rain, the most depressing kind. An all-encompassing blanket of monotonous grey and dreary guti (overcast weather), accompanied by cold drizzle and even colder wind, relentlessly sweeping the land. Tiyani’s kreb is situated deep in the bush, not far from the Benzi River. It is not possible to reach there by vehicle and we leave the Land Rover on the roadside. Hunched defensively against the combination of driving wind and driven raindrops, we make our way in single file down the familiar winding footpath. It is about three kilometres from the road to Tiyani’s house and the walk does not usually take long. Today, however, conditions are tough – we are walking into the wind and the path is slushy underfoot. Eventually we arrive. The weather compliments the mood as we stand huddled beneath that giant leadwood tree. As the raindrops splatter my upturned face, and I watch Tiyani’s wind propelled corpse swing from side to side, I wonder what kind of madness brought about the murder of such a righteous man. Furthermore, I wonder at the level of deranged insanity responsible for the desecration of the temple that is Tiyani’s body, for he has been disemboweled and his internal organs stolen by body parts dealers. Father gives a silent signal and someone shimmies up the tree and drops the hollow cavity that has housed the good soul of a humble man. The raindrops wash my tears away as I offer a silent prayer for that good soul, which, in all probability has, in its physical form, contributed to the blood money coffers of evildoers. Dealing in body parts is fairly uncommon in Zimbabwe. I personally believe that Tiyani’s internal organs were smuggled into South Africa to be sold through that thriving market. Of course, this is only assumption. Although it is probable that outsiders committed this heinous crime, they must have had at least one local accomplice who was familiar with the area and the people. Two local men were arrested and held briefly in custody, under suspicion of having been involved. After being extensively interrogated (in reality tortured) they were released without charge. The murderers remain at large, or do they? Of the two men initially suspected, one died recently after a short undiagnosed illness, and the other is currently suffering from advanced terminal cancer. The Ruware people have drawn their own conclusions from the facts pertaining to this case. I shall leave you to draw your own……… [URL=  ][IMG] ][IMG]THE SHANGAAN SONG In life, Ian de la Rue was an enigma, in death he is a legend. Powerful yet gentle, is the best way to describe that remarkable man. He was a mountain in every conceivable manner and people from all walks of life respect his memory to this day. One has only to travel about the Chiredzi area, speaking with local inhabitants, in order to appreciate the high regard in which Ian de la Rue’s memory is held. Most will have a Maware story to tell, all will recount the tale fondly, remembering a companion. Ian de la Rue, or Maware as he was affectionately known, was a friend – nay a father of the community – a man of the people. After a few years travelling the world, he arrived in the Lowveld in 1933, deciding to settle down and ranch cattle here. From then until his death in 1992 he never left the area for any significant period. Throughout that time, he worked relentlessly at developing the district and improving the living standard of the lowveld people. A son of the soil, Ian de la Rue was, above all else, a specialized cattleman. In addition to this he was a proficient crop grower, a talented and forward thinking writer, a gifted wood worker, a water diviner extraordinaire, an able but unlicensed aviator, an active community developer and a bush engineer of dubious ability! Amongst other things for there is no end to Uncle Ian, the stories shall keep his spirit alive eternally. Ian de la Rue finally succumbed to illness at the age of eighty-one in Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital city. It was never his intention to die in Harare, but circumstance prevented him from dying on Ruware in the home that he loved. Shortly after his death, his body was brought back to the Lowveld for burial. He was laid to rest beside his wife Violet, in the beautiful garden that they had created and nurtured together, as they had created and nurtured, through the years, the dream that was their lives in this remote and awesome corner of the world. The Lowveld turns out en masse for the funeral of Maware. Black and white man alike gather in that garden to pay homage to the great man. Shangaans, Shonas and Europeans, men, women and children – the entire community attends. There are cattlemen and farmers, hunters, doctors, businessmen, teachers and general workers. Seldom have I seen such a turn out in the Lowveld, or such a cross section of our society assembled together in one place. The priest commits Uncle Ian’s soul to the Lord, and then his body is interred. A short rehearsed speech of endearment and encouragement follows, something about overcoming obstacles for greater glory. It means little to me. This Harare priest did not know Maware, is not aware of the obstacles that fine man overcame in his lifetime. After this we sing a few Christian hymns. These do mean something to me, and all the more so because I recognize them as being some of Maware’s favourite renditions – I lend my voice energetically. The service does not last long and, upon its conclusion, people begin milling about, waiting to disperse. And then the Shangaan sing. “Tatani mufambile, asi emoya wamwina wahanya. Kharhi wamwine we la musaveni uherile, asi mukota gama mahaha. Hirhiseni Tatani, kalesvi hinga havako tamo kasvona. Hitekenivo Tatani, kema papa emoya Wokhukhula.†“Father you have gone, but your spirit lives. Your life on earth is spent, but with the eagle you soar. Guide us Father, in our helpless mortality. Take us with you Father, on the wings of the Great Spirit.†Whilst the service was taking place, the tribal elders had organized a choir of some of the finest singing voices available. Comprising roughly equal numbers of men and women, these songsters now stand slightly apart from the crowd, loosely clustered at the bottom of the garden. Their song is a song of heartfelt expression, a final tribute to a man who loved them as family, and a man they loved as a father. It is a seductively haunting tribute of melodious contrast, inspiring highs and lows that render the entire congregation statuesquely incapable of movement. As with most moments of wonder, it is all over far too soon. My feeble attempts at literary description are actually an insult to the choir, for it is impossible to sing the Shangaan song with ink on paper. Only rhythmic Shangaan voices are able to weave this extraordinary brand of magic. Later, after the crowd has dissipated and whilst we are cleaning up, Bharu approaches me. “Manheru bwana. Maswera sei?†“Good evening boss. How did you spend the day?†“Manheru Bharu. Ndaswera maswerawo?†“Good evening Bharu. I spent it if you spent it?†“Ndaswera.†“I spent it.†Having ascertained that we have both spent the day, we spend a few minutes chatting about nothing in particular, but I sense that Bharu has something on his mind. Eventually he dispenses with the idle chatter. “Boss, on which day exactly did Maware die?†“On Wednesday, why do you ask?†Bharu shakes his head gravely, taking his time. “We heard that it was so, that Maware died on Wednesday. We found it to be strange, very strange indeed, mysterious in fact.†At this point Bharu stops talking and begins rolling a cigarette with newspaper and rough, loose tobacco. Though I manage to control my impatience, I become a little exasperated with the rolling and ignition ritual, beginning to wonder why it was so mysterious that Maware died on Wednesday. Puffing contentedly on a thick pink Financial Gazette cigarette, Bharu eventually explains. “It is strange that Maware died on Wednesday, for on that very night a lion was heard roaring, not far from here. As you know this is a most unusual occurrence.†“Yes,†I admit, pondering a little. “It certainly is an unusual occurrence. But lions do occasionally move through this area and, in life, coincidence is common.†Bharu shakes his head in disbelief, appraising me sorrowfully before scathingly trashing my comment. “There is no such thing as coincidence. It, like lions in this area, does not exist! The difference is that lions did once occur here. Coincidence never did, here or in any other place!†I consider myself suitably chastised and decide to become less opinionated in future. Bharu takes a few seconds to calm down and retrieve his breath. “The lion is the Spirit of Maware, there is no other explanation.†Leaving this profound statement ringing in my ears, Bharu excuses himself and departs. One day, shortly after the funeral, our cook Graziano wakes me early in the morning. He tells me that Bharu has arrived and is waiting outside. I dress hurriedly and walk out into the crisp morning air. I find Bharu behind the kitchen, slurping a mug of hot sweet tea and predictably puffing on a king-size cigarette. He is uncharacteristically excited and obviously struggling to contain himself. It does not take him long to launch into speech and, as I suspected, it concerns the lion. It turns out that the lion returned once again to the Headquarters area during the night, that it had roamed about roaring constantly for many hours. As far as Bharu is concerned, this is irrefutable evidence that the lion’s presence is spiritually orientated and closely connected with the death of Maware, that the lion is indeed the Spirit of Maware. Not that Bharu needs proof. After all, he is a leader in the field of spiritual matters and has a direct hotline to the spirits. The Land Rover bounces us along the corrugated road to Headquarters. Above the noise of the engine and rattling chassis, I loudly ask Bharu how it was possible he heard the lion roaring during the night when his home is so distant from Headquarters. I know that he hears the question though he feigns otherwise. My ignorance when it comes to spiritual matters greatly perplexes Bharu, and the query obviously irritates him. I remain silent for the remainder of the journey. After arriving at Headquarters it does not take us long to find the lion tracks. Clearly discernable on the sandy surface of the circuitous road that ensnares Homestead Kopje, it is obvious that the imprints are those of a large male. After scouting around for a few minutes, I determine that there are several sets of tracks, although all the individual prints seem to be of the same size. It appears as if a group of mature male lion walked this road the night before. Of course, that is a ludicrous assumption and Bharu – an extremely capable tracker amongst many other attributes – sets the record straight. “All of these tracks belong to the same lion,†he says. “This lion walked around Maware’s house many times during the course of the night.†The evidence is staring at me right between the eyes and I feel a shiver of excitement. I find the lion’s nocturnal behavior to be very strange indeed, mysterious in fact. From his crouched position inspecting the spoor in the gravel, Bharu looks up at me knowingly. Like Ian de la Rue, that lion becomes something of a legend in our area, albeit a living one. Soon after arriving, it embarks on a cattle killing spree of monumental proportions, never attacking Ruware cattle, always crossing the river and killing on neighbouring ranches. Dad questions the elders as to why the Spirit of Maware would kill cattle, when those animals were everything that Maware held dear in life. The answer is that the lion (physical sense) has to eat, and that Maware only lived for his own cattle, not cattle in general. The elders say it is noticeable to everyone that the lion lives on Ruware but kills elsewhere. Dad decides against trying to explain that this is actually typical behaviour for an experienced lowveld lion, a lion that has spent its entire existence evading hunters and dodging their bullets! He says later that he didn’t feel it an appropriate moment to bring up the behavioral patterns of modern day panthero leo. The lion stays in our area for a marathon eight months. Several ranchers in the area suffer huge stock losses to its insatiable appetite, and a concerted effort is made by all and sundry to bring about its demise. Many people come to know of the spiritual mystery associated with the lion, and local proponents of modern Christian civilization put in much overtime in their endeavours to disprove the legend. Often I hear it said by learned men that, as soon as the lion was shot, the ridiculous fable would be exposed for what it was – witchcraft and nonsensical superstition. I am not particularly convinced. Many hunters (both professional and otherwise) work relentlessly at trying to outwit the lion, and Bharu finds their efforts hugely amusing. “It is impossible to shoot the Lion Spirit with bullets!†he says, before cracking up with laughter at the sheer absurdity of the notion. At one stage, a certain hunter (otherwise) claims to have shot at and wounded the lion. I am sceptical for this man’s hunting ability has always been doubted. Bharu simply shrugs off the claim when I inform him. “How do you wound the Lion Spirit?†he asks. “How is it possible to wound the moon and the stars, the sun and the clouds, the very heavens in their infinity? Is a mere mortal capable of achieving these feats? I think not. Tell this to your hunter friends. Tell them that they are wasting their time and can hardly afford to do so. Tell them to appreciate what time they have been granted and to use it constructively!†I deliver the message verbally one night at a social function, and my hunter friends laugh lustily at the presumptuous nature of the simple peasant and his gullible white messenger boy. They promise to re-intensify their efforts. That night I put my money on the lion, and my dubious reputation, once again, on the line. The months pass and nobody ever gets close to the lion, let alone takes a shot at it. Bharu says that Maware (as he has proudly named the lion) will always remain several steps ahead of his pursuers. That it cannot be otherwise. The hunters eventually become disillusioned with their failure. As their chances of success become more distantly remote, most of them throw in the towel, saying they have better things to do than charge around the bush looking for phantom lions. I experience smugness, although Bharu is quick to remind me of my initial cynicism. Only one resilient stalwart, a hunter of the truly professional variety, never gives up. Once, whilst huddled high in a tree blind late at night, this hunter experiences the only sighting ever made of that lion. Naturally, he is not presented with a clear shot. Later he recounts the experience to me and I shall always remember what he says. “It was weird Dave, and make no mistake. Now as you know I have hunted many lions and I don’t for one minute swallow that spiritual mumbo jumbo, but I tell you man it was weird. I could not, try as I might, get a clear shot. He stuck to the trees and weaved in and out of those trees like a ghost, never providing an opportunity. I’m sure my eyes were also playing tricks with me, somehow blurring my vision. Maybe I was just tired but the moon was full and they have never let me down before. I must say it was all very strange. I guess I was just xhausted, but I have booked an appointment with the eye specialist anyway.†I say nothing. The lion does eventually kill on Ruware and it kills quality, the victim being a prize Brahman bull from Uncle Ian’s beloved Headquarter’s herd. Ian de la Rue was a renowned cattleman, and it was always his opinion that a Tuli/ Brahman cross was the ideal animal for the Lowveld, that it produced a durable breed most suited to local conditions. In the latter years of his life, Uncle Ian kept a small herd of this fine crossbreed at the bottom of Homestead Kopje, for his own personal viewing pleasure. After passing up the sitting duck Headquarter’s herd for months on end, the lion eventually attacks them late one night, when the moon is at its fullest. Panicked, the herd breaks from the stockade, bellowing off into the night. With the exception of the grand herd bull however, which is discovered early the following morning, bitten and broken-necked but otherwise untouched, not fed upon at all. The bull killing is considered to be a most strange happening indeed, for what self-respecting lion leaves a good feed untouched? Dad approaches the elders with confidence the next day. “You said that Maware would not kill his own cattle. Therefore, the killing of the bull proves that the lion cannot be the Spirit of Maware.†Dad is confronted by a great deal of patient head shaking and sighing, before Pashela speaks on behalf of the elders. “On the contrary,†says Pashela the wise man. “Last night’s killing actually proves, without any doubt, that the lion is the Spirit of Maware. Maware is leaving us and he is taking his finest bull with him, this we know. There is no other explanation for it has been said. You may now tell the hunters to cease hunting, the lion shall not kill again in this area, for a time at least.†Pashela’s words are silently endorsed by the musing, bobbing agreement of several grey heads. Bharu arrives at Chehondo one day, not long after the bull killing. He says we should take a drive down to the Chiredzi River. Slowly we drive along the road that meanders lethargically past the picturesque Eulongwa Hills, on its way down to where the southernmost boundary of Ruware meets the Chiredzi River. On the way Bharu tells me that Maware the lion has left the area. Being a relatively quick learner, I do not ask how he came across this information. We reach the Matema road and there we find the lion’s tracks. We follow the spoor for the remainder of that day. It is not difficult for the lion has stuck to the Matema road like a mobile gravel magnet, walking in a dead straight line roughly parallel to the wending course of the Chiredzi River. We follow the trail over the Chongwe River crossing and then we reach the ranch boundary. It is getting late and we are forced to turn back. I can only assume that the lion has continued in the same direction, through Buffalo Range and Hippo Valley to Gonarezhou (place of the elephants) National Park, from where, in all likelihood, it originally came. I ask Bharu where he thinks the lion has gone. Bharu also believes that the lion has returned to the place it came from, to the Kingdom of the Great Spirit high in the heavens above. Whatever its final destination may have been, the lion never returns. Later that week, I go alone to the graves in the beautiful garden on Homestead Kopje, to honour the memory of my great uncle and that of my great aunt. It is late evening when I arrive and I remain there long after nightfall. As I kneel by the graves in silent prayer, a haunting melody, emanating from the river valley below, reaches my ears. A barely audible hum to begin with, it is gradually transformed, by way of dozens of synchronized voices pitched to opposite and absolute extremes, into the harmonious enchantment that is the Shangaan song. Tatani mufambile, asi emoya wamwina wahanya……… Father you have gone, but your spirit lives……… | ||

|

| one of us |

I've got a copy of Dave's book and recomand it to anyone interested in Africa. JPK  Free 500grains Free 500grains | |||

|

| One of Us |

Dave, do you have copies for sale? If so, how do I order? thanks Steve "He wins the most, who honour saves. Success is not the test." Ryan "Those who vote decide nothing. Those who count the vote decide everything." Stalin Tanzania 06 Argentina08 Argentina Australia06 Argentina 07 Namibia Arnhemland10 Belize2011 Moz04 Moz 09 | |||

|

| One of Us |

Hi Steve You can contact a guy called Bryan Patton, in Plano, Texas. Here are his contact details: email: bryan@africanhuntermagazines.com phone: 877-261-4226 I understand the cost is $20, don't know what the postage deal is though, probably a couple of bucks more. Thank you very much Sir - I am a new member on this site, and you and your friends have already given me a great deal of encouragement. It is much appreciated | |||

|

| One of Us |

Hi david, Love the storys. I will be in Bulawayo next month, Is there any where I can get my hands on a copy? Regards, Adam | |||

|

| One of Us |

ozhunter No problem. Where will you be in Bulawayo? If you can get an address to me, I'll make sure a book is delivered there before you arrive. Thanks for your interest Sir. Dave | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Hunting

Hunting  African Big Game Hunting

African Big Game Hunting  Stories: Guardian of the Ruins; The Baboon Feast; The Shangaan Song

Stories: Guardian of the Ruins; The Baboon Feast; The Shangaan Song

Visit our on-line store for AR Memorabilia