The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Other Topics

Other Topics  Recipes for Hunters

Recipes for Hunters  Native American Frybread

Native American FrybreadGo  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| one of us |

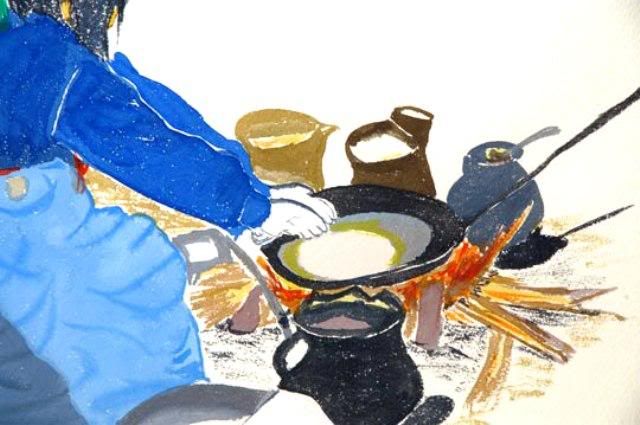

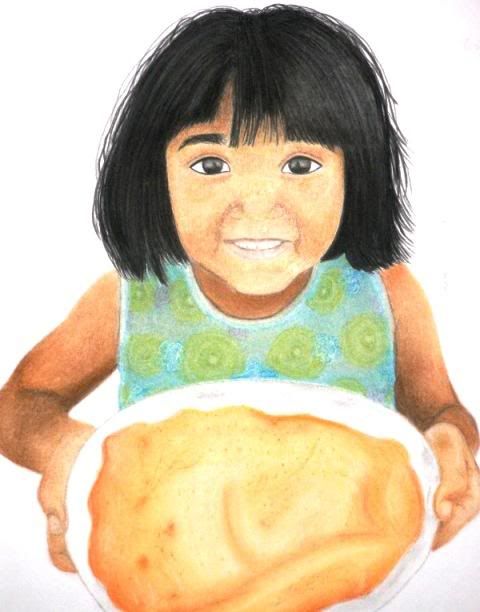

Native American Frybread For the Native American tribes of the United States, frybread is a mixed bag. It is a food that is a reflection of their history and culture, and encompasses some of the most basic and fundamental philosophies of the people who made it. Its shape is a circle, the sacred hoop without end, and a metaphor for the double-facted nature of life. It is old, yet new; modern, yet traditional. It is a symbol of defeat, and a symbol of resorcefulness; it is a symbol of poverty, and a symbol of generosity. It is a reminder of lost freedoms, and a reminder of cherished memories; a reminder of conquest, and a reminder of hospitality. It is an example of making what you can with what you have, and transforming adversity into comfort.  Frybread is nothing new; it is found in various forms in many corners of the globe. In the United States, however, it is the history behind frybread, just as much as the ingredients, that make it a traditional food and common experience among the Aboriginal peoples of North America. Beginning in the mid-1800s, the concept of frybread began to come into focus as a product of contact with Euro-American society. Among many tribes, frying cakes made of corn or other ground seeds in animal suet or tallow had been practiced for some time, using shallow or improvised cookware; however, it was after the Natives were able to obtain deeper, cast-iron pans through trade that deeper frying became more common. Along about the same time, western tribes began to receive other very basic (and often low-quality) staples such as beef, bacon, hardtack, sugar, coffee, flour, salt and lard. These staples were, at first, bestowed by the "generous White Father" upon America's "domestic dependent nations" as gifts during treaty negotiations, and also as resulting annuities once the treaties were concluded. Later, as the tribes were systematically conquered, subjugated, relocated or simply herded onto reservations, frybread emerged as an improvised product of the government-enforced dependency on federal rations and, later, commodities.  By the very early 20th Century, nearly every tribe in the lower 48 had a version of frybread; families served it at every meal, and it became as common in reservation life as the rising sun or the birds in the sky. American Indians are, by and large, a resiliant, communal people, and even in the drudgery of defeat, the twin virtues of hospitality and generosity were able to re-assert themselves into traditional Native culture. Once again, people begain getting together for festive gatherings at any opportunity; naturally, the common, inexpensive frybread, so easy to make for a crowd, was profusely available.  The magical combination of warm, filling food and a crowd of people with something to celebrate is inconquerable. Over the years, frybread, the very symbol of subjugation, defeat and dependency, underwent a transformation into an epitome of family, fellowship, good times and cherished memories. In modern terms, it became a cultural comfort food, a not-quite-old tradition that has permeated every aspect of Native life, and has even been elevated into fodder for "new" Native folklore, as seen here in this clip from the 1998 movie, Smoke Signals, in which Victor's mother, Arlene, prevents a frybread riot: In its most basic form, frybread is extremely simple: flour and water mixed together into a smooth dough, shaped into a circle and fried in hot fat. In nearly every recipe, baking powder is added for leavening, although sometimes yeast is used. Salt (and sometimes sugar) are added in small quantities for flavour. Another ingredient that is occasionally found is milk (or, more traditionally, powdered milk, since fresh milk was rarely, if ever, available). Although the use of milk or yeast seems to be at least partially regional, it is a safe bet that the more basic (and less complicated) it is, the more traditional and "historical" it is. Though the ingredients are for the most part universal, it is also very individual to regions or tribes, with unique tastes and textures due to slight differences in preparation, such as the way it is kneaded or the fat it is fried in. Frybread can be served with literally almost anything; common accompaniments range from butter, honey, cinnamon and sugar to chili, cheese, meat and taco or pizza toppings. In my area of north-central Montana, frybread culture is found among the Lakota, Gros Ventres, Assiniboine, Blackfoot, Chippewa/Cree and Métis peoples, as well as the Cheyenne and Crow, farther south. These northern plains tribes tend to use a chokecherry concoction that the Lakota call "wojapi, which is somewhere between a compote and a syrup. Here's how it went down when I made frybread recently for the family. You don't need much, just this:  And some fat of some kind; lard, shortening, or cooking oil:  I started the oil heating over medium heat while I prepared the frybread dough. You want to have 1.5 to 2 inches of fat in a large pan or deep fat fryer - cast iron is perfect for this. The beautiful Mrs. Tas descends directly from the Blackfeet Nation, which lived a nomadic life - following the migrations of the buffalo - in the area from the Rocky Mountains of Montana to the North Dakota border; from south of the Missouri River north into southern Alberta and Saskatchewan. This means that frybread is more than a just product of our region, it is a part of my family's heritage, and I used a recipe that is, as far as I can tell, fairly traditional to the Blackfeet culture. For each "batch" of frybread: 3 cups flour 1 tablespoon baking powder 1 teaspoon salt 3/4 to 1.25 cups warm water It's not complicated at all - as mentioned above, this method comes from a time and place where there was no room for elaboration or frivolity. Just combine dry ingredients in a bowl; first, the flour:  Then, the salt and baking powder:  After stirring the dry ingredients around together with a fork, I then mixed in the warm water:  You want to start with just under a cup of water, and then add up to another half cup if necessary in order to make a stiff dough. Knead the dough until it is very elastic (it is very important to knead the dough well); you're looking for a smooth, soft, flexible dough that isn't sticky:  I repeated the above steps, since I was making two batches; then, we began working with the dough. For some reason, I didn't get a picture of the dough circles that I made (although there is one farther down during the cooking process that will give you an idea), but once again we're not talking about anything very complicated. You just need to tear off balls of dough that will flatten into round circles.... But how big should those rounds be, you ask? Well, that's really up to you; I've seen frybread 4 inches across and I’ve seen it 8 inches across, and everywhere in-between. I am sure that it can also be bigger or smaller, as well. Blackfeet fry bread tends to be smaller when compared to frybread in the Southwestern US - closer to 4 inches across - but since I wanted to use the frybread for multiple purposes, I tried to keep them at about 6 inches across; it really is up to you, as long as it fits in the pan, I guess. As far as thickness goes, you want the rounds to be around 1/4-inch thick. When flattening the balls into rounds, keep in mind that dough shaped by hand will result in more tender (tenderer?) frybread than dough rolled with a rolling pin. Then comes another question of import: should you punch a hole in the center, or not? Well, once again, the answer is partly a matter of tradition and partly a matter of preference. In many tribes, a hole was punched through the center in order to help cook the frybread more evenly and decrease the chance of air bubbles; however, in some areas no hole was punched and it seemed to turn out fine. In this preparation, I made some with a hole and some without - and then with some, I cut a slit rather than punched a hole. All seemed to come out about the same, but I think cutting the slit worked best...for me. It allowed even cooking, but also, as the frybread rose and swelled in the hot fat, it closed up the "hole" so that the toppings we planned on using later wouldn't fall through. It worked for me - use whatever method works for you. In any case, you want to have the dough shaped, flattened and ready before you start to cook, as the cooking process goes pretty fast. When the time comes to begin cooking, the fat should be quite hot, almost to the point of smoking. As for the cooking, once again, it's easy: simply fry the rounds one at a time, dropping each into the fat to cook for a few seconds (the time will vary according to the temperature of the fat), then flipping it over when it gets golden brown  And cooking the other side for a little longer until it is also golden-brown. Nothing could be easier, if you ask me, to produce such good results. What you end up with is a wonderful-smelling, warm piece of fry bread that is just crisp on the outside and tender-chewy on the inside. Here's another one:  As they come out of the fat, you want to drain them on paper towels:  Looking here, you can also get an idea of what the flattened rounds should look like. Contrary to the picture above, I found that the best results came from the bread when I put a paper towel between each finished round:  When all the rounds are transformed into golden, delicious frybread, you're done and ready to eat! But don't be so eager that you forget to shut off the heat to the oil - that could have some disastrous results. Frybread can be served as-is, or with a little butter on it to accompany a meal, sopping up broth, gravy or other stuff. This is surely how it was used day-to-day as the native peoples struggled to transition their cultures and lifestyles with all the strikes against them; but as mentioned above, frybread grew into something more as the people persevered and found reasons to celebrate. Eventually, frybread became the basis of so many wonderful things, to be shared with family and friends. We all have our favourite ways to serve it; for the beautiful Mrs. Tas, it is a mixture of butter, honey, sugar and cinnamon:  While mine is with wojapi and maybe a little butter.  The two examples above show fry bread as a "snack" or a dessert, but that's not all you can do with it. I looked around the refrigerator and pantry to see what we had, and came up with some ingredients for a veritable feast:  One of the most popular modern uses for frybread is for "Indian tacos;" You can find them everywhere in Indian Country, on the street, in cafés and restaurants, at fairs and festivals, and of course at pow-wows. Using "taco meat," refried beans, taco sauce, cheese, sour cream, tomatoes, olives and spring onions from our own garden, we transformed some of the frybread into Indian tacos:  Then, using pizza sauce, cheese, pepperoni, olives, mushrooms, we made a few "Indian pizzas" as well:  Easy as can be, and extremely versatile, frybread can serve as a reminder to us all that good things can come from tragic situations, and that the concept of "peasant cooking" - making the best of what you can from what you have, even in poverty - can take on many delicious forms. The examples above, showing a few various incarnations of frybread, were warm and cozy, truly speaking to the heart of home, friends and family. They are what we did in our home - how about taking up the thread and seeing where it leads, and what you will do with frybread in your home? | ||

|

| one of us |

Please permit my respectful question. Why use....bother with .... go unnecessarily length to use .... allow the inane PR to promote the use of....."sea salt"??! Sea salt has **NO** flavor or nutritional enhancement greater than deep-mined salt. Indeed, sea salt, a product of ocean desalinization, carries with it an unendingly collection of pollutants which had earlier been introduced, directly or indirectly to the ocean from sewage, heavy metals from mine tailings, other industrial waste, agricultural runoff - including pesticides, animal waste and fertilizers, an on and on...ad infinitum. Just (try to) imagine what chemicals and debris have been generated by human civilization ... you WILL find ALL of that in "sea salt". Yet, the product is marketed, and people buy and use it. **WHY**!!!. Mined salt, in contrast, is a PURE substance. Oh sure, it may include tiny amounts of harmless inorganic salts generated naturally through Earth's geologic processes. But, it does NOT carry the garbage ... alot of it - harmful (toxic,and/or carcinogenic), that is ALWAYS found in sea salt. The stupid, self-promoting pundits of gastronomy promote subtle and unique flavours of different sea salts. It's all BULLSHIT. | |||

|

| one of us |

it's what i had, so i used it? | |||

|

| one of us |

Hey!!! I am not picking on you!!!....HONEST!! I saw the picture, and my hair trigger yanked. There are SO many rip-offs, scams and wrongs perpetrated upon us ... all around us....regarding everything. Nope: I am NOT Chicken-Licken. Trouble is, we cannot know all about "everything" to protect us, even from well-intentioned "errors" (and there are very few of those). Just know that it only takes ONE molecule of a carcinogen to affect ONE site on a DNA molecule to cause a mutation. If that mutation is viable, the cell divides and divides ...carrying the mutation to all successive cells. Think: Cancer. And think that cancer rates are rising steadily. Don't believe the hype that "we are winning the battle" We are not. Anything we can do (damn little) to avoid consuming (or exposing ourselves in any way) to mutagens/carcinogens, offers us a chance at a longer life. Sea salt is only a micro-microscopic part of the problem. OK, I quit. | |||

|

| one of us |

well, my wife got it for me, saying that she thought it would be good for my cooking projects ~ hopefully she wasn't trying to kill me! i like the stuff personally, but i like pretty much any salt, even iodized ~ | |||

|

| one of us |

Hi again.......yeah, he's baaaaack.... I LOVE your recipes, your pictures, your description and ..... Montana.....and I envy your living there. I know I'm being an idiot to rant ..... and I mean no offense. I also do not mean to mis-use this wonderful site (that I visit at least 20 times a day). No-one of us can save the world. Maybe, each of us might save a tiny part of it??? BTW, iodized is OK....even necessary (as a dietary source of iodine ....for your thyroid). For a salting brine, I use kosher salt (not iodized) although I am unsure why it might be preferred. | |||

|

| one of us |

lol - no worries, mate ~ but you do have me interested, so i will defintiely be doing some research ~ | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Other Topics

Other Topics  Recipes for Hunters

Recipes for Hunters  Native American Frybread

Native American Frybread

Visit our on-line store for AR Memorabilia