The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Guns, Politics, Gunsmithing & Reloading

Guns, Politics, Gunsmithing & Reloading  Gunsmithing

Gunsmithing  (Complete Report and Pics 3/11!) Two Days with D'Arcy Echols - Making a Mauser Feed

(Complete Report and Pics 3/11!) Two Days with D'Arcy Echols - Making a Mauser FeedGo  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| One of Us |

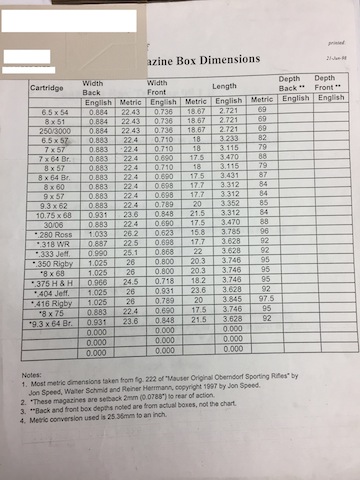

**AUTHOR'S NOTE**What you are about to read and/or watch is entertainment. It is NOT a strict tutorial. It is an attempt to describe the experience of what it was like to spend two days with D’Arcy learning to remedy a single issue with a rifle – its feeding. It is a long narrative. The point was not only to explain the process of how the job was accomplished for this particular rifle, but also give the reader some access to the thoughts and conversations that bloomed during the process. It is of necessity a reductive work. It would be impossible to include every bit of knowledge and skill that informed the decisions along the way. That, after all, resides with D’Arcy. Still, for the patient reader, there is ample information to glean, and I hope it is at least worth your time reading it. Should the reader not find the narrative entertaining or interesting, I would extended the invitation to do what I did: book some time, tickets, and rooms, and head to Utah. I would be as eager to read your story as I hope you are mine. I am deeply indebted to D’Arcy for his assistance and willingness to help me out on a rifle he did not build. If I were in the business, I can’t say I would have been so kind. I am one lucky sod… (You Can't) Just Change the Follower - YouTube The Rime of the FN Mauser In Six Parts Part the First D'Arcy cut the engine, opened his door, and got out of the truck. I opened my own door, got out, and shut it hard. I walked around the rear of the truck, trying not to slip on the ice, and approached the steel door. D’Arcy was fitting a key into the door’s lock and said, “Guys walk into my shop and expect to see a team of German engineers standing around in white lab coats. They are sorely disappointed when they find out it’s just me.” The door squeaked open, and D’Arcy flicked on the lights. He was pressing numbers on a keypad as I walked in. The shop had the look as though someone had just tidied up; it looked ready for something . Technically, this was not the first time I had ever been in D’Arcy’s shop. The day before, I had made the long trip to Logan: Washington Dulles to Houston to Salt Lake City, then a shuttle service for the final two-hour drive from the Salt Lake City airport to my hotel. (The drive was nearly adventurous, due to a van whose transmission slipped so often I was convinced I’d spend at least a portion of the trip pushing it, and a driver who had a tendency to talk to himself in complete sentences. At times he gesticulated to make his point to himself, and I anxiously counted the minutes until I arrived at the Holiday Inn Express.) D’Arcy offered to pick me up for dinner on my arrival in Logan, and after a long day avoiding overpriced and under-flavored airline food, I was looking forward to a decent meal. Seven minutes after I checked in and notified D’Arcy I was at the hotel, I was in my room about to put my feet up for a minute when an electronic message came through, “I’m in the lobby.” Prompt, that Echols. Before we left the hotel, D’Arcy asked me to grab my rifle and said we would drop it off at the shop before dinner. This would give me an opportunity to take a look around and see where the magic (hopefully) would happen, but also, as it turned out, would be the first opportunity for D’Arcy to inspect my rifle to gauge the true extent of the work that lay ahead. But I’m getting slightly ahead of myself – you don’t even know why I was standing in D’Arcy’s shop in the first place. Come, follow me, all ye Fortunatos. The nitre! – see, it increases… It all started with a rifle. I had this 9.3 x 62 Mauser based on an old FN action that, over the previous year-and-a-half, had, to put it kindly, seen its ups and downs. The thing suffered from mis-drilled-and-tapped scope base holes, (which eventually required custom bases to correct), a broken two-position safety, (courtesy of poor packing and the monkey-handlers at UPS), and a replacement 3-position Recknagel safety that required additional fitting… and then there was the feeding. Yes, the rifle “fed,” but it didn’t feed like a finishing-school debutante; with smooth, graceful movements; minding the teeth on the tines of the fork, and never, ever letting any of the food fall back on the plate. No, this thing fed like a fat kid at a pie-eating contest; elbows on the table, two hands at once shoving in fistfuls of pie, and as much falling back onto the plate as was going in. In short, it needed some - finishing. Like many readers, your humble correspondent had taken up the oft-illusory habit of referring to the Internet and websites to solve particular problems in the realm of rifledom. This I did with great aplomb, having eventually convinced myself that roughness was the major cause of my problems, and that the deft application of various grades of abrasives would surely do the trick. I even referred back to the brochure I helped Duane Wiebe put together (layout, not content) on converting a standard length Mauser action to a .375 H&H. It looked straightforward enough. I thought I understood the process, and I got to the point where, I almost – almost, I say - hit the “Confirm Purchase” button on a shopping cart full of stones and other items from Brownells. Then I stopped. What the hell was I doing? Take a 500-piece puzzle, dump the pieces on a table face-up, and have a good look. You are, in fact, seeing the same image - the completed puzzle- that is on the front of the box. Every detail is there, every highlight, every color, and every shape. The reason the image does not complete itself in its fractured state is that there are no relationships between those highlights, colors, and especially shapes, in order for the image to makes sense. Each of those pieces (and its content) must form a relationship with another piece to help complete the picture. It is a similar idea as an impressionist painting, say George Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grand Jatte , where a collection of points of color are individually vague, but when seen at a distance (allowing them to spatially relate to one another), the picture comes into focus. The same applies to many Winslow Homer paintings, in which a simple swipe of color by itself is largely meaningless, but properly related to other swipes of colors defines lips, eyes, cheeks, and eventually, faces, some showing patience or placidity, others anguish. When it came to this Mauser, I was missing the picture. I was focusing on a single puzzle piece (feeding) and not seeing the issue as a component part of an entire, interdependent system. I was looking at the pieces of the Mauser; I wasn’t looking at the Mauser. I didn’t know where to start, where to go if I did start, and more importantly, when to stop. After all, you can take metal off, but putting it back on is, well, something different. That’s when I took a few pictures and sent them to D’Arcy. I got to know D’Arcy many years ago via a somewhat anfractuous email conversation regarding, of all things, Harry Selby’s .416 Rigby. He knew Harry, I knew Harry, and the ensuing conversation among the three of us (and others) regarding safeties and magazine capacities gave us plenty to talk about. I first met D’Arcy in person at the 2013 SCI show in Reno, NV, where we chatted at length about his Legend and Classic rifles (and of course, Harry’s .416), and it became quickly obvious he - to use his phrase - knew sheep shit from cottonseeds. It seemed to confirm Harry’s private comment to me that D’Arcy was one of America’s top gun builders, and I enjoyed the long conversation about the minutest detail of his work. For every question there was not only an answer, but also a justification as to how the answer was derived. He was not merely concerned with the result, but equally the process of achieving the result. This type of thinking resonated deeply with me. As an inveterate “why” type of person, it is almost never enough for me to simply know that a thing works – I want to know why and how it works. D’Arcy responded to my emails with more questions. I sent more pics. More questions. More pics. He said he would be willing to do the work, but then on December 7th, (another day which will live in infamy – for me at least) he sent the following message, “Or you could physically bring that barreled action here and spend a day doing it yourself, under instruction.” This piqued my interest. I’ve never had any delusions of mechanical ability – even though this whole thing started with me thinking I did, as I added files to the shopping cart at Brownells. But the thought of spending a few days with D’Arcy and knowing he would likely hit me with something rather dense before I made an irreparable mistake gave me the small boost of confidence that I needed to proceed. I told him I would check my schedule and see if I could find a weekend to add a few days to and get back with him. It turned out February 9-12 was the only long weekend that would work for me, and when D’Arcy respond with his own message, “Works for me,” the die was cast. The economically minded among you are certainly scratching your heads at this one…. What kind of fool buys plane tickets and hotel rooms, takes two days off work, then flies his rifle all the way across the country for feeding work when he could just mail the damn thing and sit back and wait for the doorbell to ring with the completed work? Trust me, I thought of it too, but as I’ve aged in my cask, I’ve begun to realize that a direct dollar-for-dollar ROI isn’t a necessary requirement to justify spending a little money. Maybe I was throwing good money after bad here, but then again, how many average folks have been able to spend time under the tutelage of a master working on their rifle and have a story to go along with it? I’ve only talked to one other; a pleasant chap with a similar story, and whose credit card is still recovering…. I would turn it into a project. Given I would have the undivided attention of one who knew, I’d use this opportunity really get a handle on what it took to make a Mauser feed, and maybe write about what I learned. Money sufficiently justified, I booked my seats and rooms. Many people refer to the Mauser 98 as the Mauser System 98 or some derivation thereof. “System” is an interesting word to use for something that many, myself included, generally think of as a single, static piece of metal – the action. OK, two pieces; the receiver body and the bolt. Systems are composed of individual, interconnected pieces that, together, work to perform a certain function. It infers there is a beginning of a process, and an end. But, what was the first step in the feeding function of a Mauser? The last? What happened between the first step and the last? Did it start with the bolt closed, or open? What parts of the System 98 affect feeding? And when it’s broken and the bullet either jams hard left or right into the ring, or the cartridge rim does not properly snap under the extractor - how do you fix it? Tickets and rifle in hand, I drove to Washington Dulles airport and began the long trip to Utah to find out. Part the Second To say the process of making the rifle feed didn’t go as I expected would be an understatement. That evening, when we stopped by the shop to drop off the rifle, I removed the rifle from its case and handed it to D’Arcy. “Hmm. Hmm.” He said. I wasn’t sure if that was a good thing or a bad thing. “Where are your dummies?” Once the trip was confirmed, D’Arcy asked me to make up 20 dummies using my chosen brass (Lapua) for proving, five-each of four different bullets, with one being a flat-nose if available. Flat-nosed bullets have an almost legendary status, both for their ability to penetrate straight, but also to prematurely age gunsmiths who are commanded by their clients to get them to feed under all conditions. I wasn’t one of those clients. I just happened to think the Cup Points were interesting and had some on hand. If they didn’t feed, no worries, I had no plans on shooting buffalo with the thing anyway. For my proving rounds I chose the North Fork 286gr SP (my preference for this rifle), the North Fork 286gr Cup Point, the Woodleigh 286gr SP, and the Swift 300gr A-Frame. The latter would turn out to be a troublesome choice – but more on that later. He took a single round loaded with the North Fork Cup Point and inserted it into the magazine. As he pushed the bolt forward, my eyes went wide with anticipation (no, I had not tried these myself – there was no point once the trip had been booked). Would it feed properly – exiting the magazine smoothly, the groove of the brass snapping gently but firmly under the extractor as it left the rails, and then pointing itself toward the chamber and staying straight as the bolt was closed and locked? Turns out, no. As I had seen before, the dummy stayed ass-down too long, creating an exaggerated upward angle that continued as he pushed the bolt forward, resulting in the North Fork lodging against the inner/upper surface of the H-ring of the Mauser. Shit. More “Hmm. “Hmm.” D’Arcy removed the dummy, then the bolt, then promptly grabbed a screwdriver and disassembled the rifle. “Where are your calipers?” (He had asked me to bring a set if I had them). “Hmm. Hmm,” He said, as he took several measurements from the magazine box. My hands felt clammy, my pulse raced. I wondered just what the hell had I gotten myself into…. “We’ve got our work cut out for us,” he said. “Let’s grab a bite to eat.” With that, he set the magazine assembly on the bench next to the barreled action and we left for dinner. My appetite, previously ravenous, had been hollowed by the cryptic “Hmms.” Luckily it regained its previous state on the drive to the restaurant. Part the Third The next 36 hours were a blur. Once arriving back at the shop after my 7am pickup, I immediately knew I didn’t know anything about how to make this Mauser feed. D’Arcy handed me a clipboard with a piece of paper that had something that looked suspiciously like math printed on it. This wasn’t quite what I expected. My nascent understanding of how a gunsmith made a Mauser feed was to stuff the magazine full of dummies and slowly feed each round, filing a bit here, polishing a bit there; maybe widening the ‘flare’ of the rails and slicking up the ramp. We’d take our time, shoot the breeze about one thing or another, grab dinner and I’d feel like I actually did something. That’s not how it went. Who said anything about math? Without sounding like he was talking to the dolt I actually am, D’Arcy gave me a quick lesson on magazine box geometry; something about the cosine of 30 degrees multiplied by the base diameter added to the base diameter and VOILA! You have the proper width of the rear of the magazine box. We ran the numbers using a calculator, then, he taped three of my dummy rounds together and asked me to measure what is essentially the height of the triangle they made at the cases base. “.880.” “Now do it again 2.039” from the base.” “What’s 2.039?” “The shoulder location.” “Oh.” I measured, and then ran the numbers again. “Closer, .840” and .841”, respectively” “Now, use the worksheet I just gave you and measure the box dimensions at the base location and the shoulder location. This will tell us where we are now and how much work we’ve got ahead of us.” “.895” and .812.” (For the record, Mauser’s formula indicates these dimensions should be .888” and .841” respectively.) The fact is, D’Arcy already knew these numbers. These are the dimensions he quickly checked the previous evening before dinner. (I found out later that he had even slipped back to the shop after dinner for a more thorough inspection.) But, being the fine instructor he is, he walked me through the process as to not deny me my own moment of discovery. As the numbers told, the box was mathematically a little too wide at the base location, but more critically, it turned out that magazine box was radically too narrow at the shoulder location. This meant that the rounds were pinching at the shoulder and, for lack of a better word, ‘hinging’ off of each other. Placing the follower in the box while it was sitting flat on the bench confirmed this. When loaded with dummies, the rounds were not fully supported along their length. They shimmied and wiggled when touched. A picture (and a question) was starting to form in my head. “So essentially, in an ideal situation, we need the same taper from the base to the shoulder within the box as the taper predicated by the taped cartridges (or math). That way, when the rounds are stacked in the box in an unrestricted manner, the follower and sides of the box allow the rounds to form an equilateral triangle. “Correct. That was Mauser’s solution to the staggered column magazine, and it's been working just fine for quite some time - if you follow the rules.” Another, more illuminating, question came to mind. “And that means that since most cartridge case dimensions are different, the magazine box geometry must be specific to that cartridge – meaning no one-size-fits-all solutions.” “You’re learning,” he said. He smiled (or was it a smirk?) and handed me a piece of paper with “Magazine Box Dimensions” printed across the top and a table of numbers below. The left column listed 23 common Mauser cartridges, the columns to the right their respective magazine box dimensions – rear width, front width, and length. Out of the 23 cartridges, there were 17 unique magazine box dimension combinations. This was a revelation to me. It not only gave me a new appreciation for Herr Mauser and his handy-work, it also told me – given the exactitude of matching magazine box to cartridge – just how damned important getting the magazine box geometry right must be for proper feeding. An epiphany! THIS is where proper feeding starts; not with the action body, the bolt, or even the magazine box – it starts with the cartridge itself. A cartridge’s dimensions have a direct effect on its feeding potential (or maybe the potential amount of work needed to get it to feed). Short, fat, Guido-the-Gangster-necked cases have a lot of work to do in a short amount of linear distance (bolt throw), whereas the longer, Audrey Hepburn-necked 300 H&Hs give the builder more time to address each step of feeding from magazine to chamber.  For the experienced among you, this is nothing new. But I’m a plebe, and understanding the proper logic and reasoning behind this seemingly obvious process was revelatory. A thought crept into my head – intentionality. This applied not only to Mauser and his system, but also D’Arcy. As I was to learn over the next day-and-a-half, D’Arcy is one of the most intentional people I have ever known. Another thought crept into my head as well – the number of times I had asked uniformed questions about Mausers based off on my erroneous understanding of how the system worked. If you were ever the recipient of one of these questions, you’ll hopefully accept my apology…. I looked at D’Arcy, beaming with my newfound knowledge. “And some people think all you need to do is change the follower.” He said. Part the Fourth The magazine box was oversized at the rear by .007”, so there was little we could do there – the shoulder area was another story. We subtracted the actual box width at the shoulder from the ideal width, and divided it by two to find the amount of metal we needed to remove from each side of the box to achieve the proper internal taper. This was .0145.” Doesn’t seem like much, now does it? The astute reader is surely wondering if - considering the additional .007” (.0035” per side) at the rear of the box - we would also add a commensurate .003” to .004” extra per side at the shoulder to match? Nope. The wall thickness of the magazine at the top of the shoulder position would be just too thin at .011”. I was quickly learning that to be slightly too wide beats slightly too narrow at either location. We were already dancing in a minefield and didn’t need to meet Bouncing Betty. “Before we get to cutting, let me show you something,” he said. D’Arcy walked over to the bench, grabbed a couple magazine boxes and a pen, and adjusted an articulated architect’s light. He held what turned out to be one of his custom magazine assemblies (this one for a .450 Rigby on an FZH action) under the light and pointed to the inside the box with the pen. “This is a good time to point out the relief cuts within any original Mauser magazine box. These ‘pockets’ reduce friction between the inside wall of the magazine box and the straight-walled cases.” He pointed to what you might think of as the inside of the ‘cheeks’ of the magazine box. There were two vertical steps, between which was a very slight recess – maybe .005” to my untrained eye. He stacked in a few cases and I noticed how the majority of the case between the shoulder and the base rested between the two steps but did not make full contact with the side of the magazine box. “If you remember your history – Paschendale, for example - you’ll recall that trench warfare wasn’t always fought under bluebird skies. Quite the opposite actually, rain and the resulting mud often ruled the day. “This cavity begins approximately .250” ahead of the back wall of the magazine box and can either terminate just behind the shoulder position or be carried forward so the necks of the loaded rounds actually have the correct cosine width and the shoulder area is slightly wider to allow for this clearance. It all depended on the blueprint from the home office for that particular contract.” He set down the .450 Rigby magazine and picked up another box, this one lacked an attached trigger guard and front tang. “This clearance idea can also be found on the Winchester Pre-64 magazines.” He pointed to four ridges on the inside of the box, two on each side, fore and aft – like emergency doors on each side of an airliner. This really does make a difference, as does the wide recess at the rear of the spring pocket, which allows the tail end of the spring to articulate left and right in the floorplate as rounds are stripped from the magazine. A tight fitting spring pocket that retards this springs movement is not a good idea. Currently designed magazine assemblies usually omit these features.” He set the magazine box down and picked up yet another and pointed to the inside. “Here’s another. Note how there are only two clearance ridges at the front.” “Why is that?” The question hung in the air. “This box is for a 375 H&H.” Silence. “What does a 375 H&H have that a .30-06 doesn’t? “A belt.” “Let’s get to work” D’Arcy clamped the front tang of the magazine box into a special fixture (it’s ALL about fixtures, as I was to find out), and then clamped the fixture into the vise on his Bridgeport. With a dial indicator installed in the spindle, he adjusted the table until the indicator just touched the rear inside of the magazine box. Then, he ran the table along its X-Axis checking the amount of taper from the rear of the box to the shoulder location. After each pass, and with the vise loosened, he rotated the vise by slight taps and rechecked the taper. Once the indicator read 0 at the rear of the magazine and then half the required offset to give us the additional width required over the entire desired length of travel, he locked the vise. The rear of the magazine box, which was resting on a steel block, was clamped – a penny acting as intermediary between the hardened clamp and the not-as-hard trigger guard. A ¼ OD long cut length ball end mill replaced the dial indicator in the spindle and the machine whirred to life. Soon, very fine curls of metal were spinning off the cutter and the inside of the box began to shine as light reflected off of the raw metal. It took seven passes to complete the operation, working progressively from rear to front in small steps, each pass taking a mere .002” more metal, with each pass stopping at a predetermined distance that was just ahead of the shoulder length on the case at the front of the box, which was confirmed by a table lock. The last few passes were nerve-wracking. As we approached our goal of .014” metal removal, the top of the box became perilously thin. The bottom of the box was fine, but, given the outside profile has a 2-degree taper, each pass of the cutter moved this edge closer and closer to a knife-edge. The last .004” of cutting made the short hairs tingle. But cut it we did, and, I thought we were finished with half of the operation. Not quite. A flat end mill replaced the ball end mill and I learned about a process D’Arcy called “sparking,” whereby we ran the cutter back and forth along the newly milled surface to clean it up and to square the bottom of the cut. Even finer pieces of metal slung off the cutter, and, not being a machinist, I asked yet another dumb question. “Why does the cutter continue to remove metal pass after pass if we aren’t running it deeper into the side?” “Very carefully, reach around and touch the side of the magazine box while I move the table.” It all became suddenly clear. The side of the magazine box fluttered with the rotating cutter. It was ever-so-minutely flexing as the cutter passed back and forth. Got it - the multiple passes were necessary to overcome the flexing and to smooth the surface, which would then be stoned and sanded even smoother. We lathered, rinsed, and repeated this exact process on the opposite side of the box, and once again, I prematurely thought the magazine box operation was finished – nope. The next step required yet another measurement, this time across the bullets as they lay in the same orientation as they would in the magazine. “No sense worrying about the box geometry relative to the cases if you are going to let the bullets drag at the front, now is it?” I measured the maximum neck OD width of stacked cases using the North Fork Cup Points (these carried their full diameter farther forward than the others) and we exchanged the flat end mill for a 9mm end mill, which matched the radius at the front corners of the magazine box. After a few passes to slightly increase the width of the front of the magazine box for clearance, we removed the magazine from the mill. It was time for a test – but not feeding – not yet. D’Arcy dropped the follower into the magazine box and loaded three of the Cup Points on top of it. Like a sommelier judging a wine’s color, he lifted the assembly and held it to the light. “Hmmm.” There it was again. He handed the assembly to me and told me to hold it up to the light. “Do you see light on either side of the bullets?” “Yup.” “Good.” Then, with the assembly on the bench, he showed me how the dummies no longer “hinged” like they did before the machine work. They laid on each other like a well-stacked cord of oak. This was progress.  Continued in next post... | ||

|

| One of Us |

Part the Fifth While I was de-burring the magazine box with a hardened triangular scraper and then polishing it with a series of stones and wet/dry paper, D’Arcy was busy fiddling with something on the Bridgeport. I wasn’t paying all that much attention, but when I glanced up and saw what he was installing on the table, I had to take a look. It looked like an overbuilt sewing machine, and I thought it must be for some other project he was working on – I had no clue what it did. “This is an action fixture Tom Burgess built. Take a good look, ‘cause there's only one, at least that I know of.” This gave me a clue to where we were headed next. I finished up polishing the magazine box – I was chuffed at my handywork – and on D’Arcy’s approval of the job, I breathed a sigh of relief. Little did I know how much more handwork was to come. D’Arcy told me to grab the barreled action, and as I did, he pulled what looked to be an anvil base out of it’s nook. On top was what I recognized as a barrel vise – this one happened to be designed and marketed by Jerry Fisher. He inserted the barrel through the opening and cushioned the protected the metal with layers of an old timecard cut into small squares. He tightened the four bolts on the top, and then assembled what looked like an oversized wrench over the front ring of the action. “Let’s see how tight this thing is.” He gave it a whack with a deadblow hammer. He looked at me sideways. Then he gave it a bigger whack – the action wrench gave way, and he spun the action off the barrel. We removed the wrench from the action and the barrel from the vise. As he removed the barrel, he looked at the chamber. “Hmmm,” he said. There it was again. “Mausers should have a fairly defined radius at the chamber mouth, we’ll have to clean this up. Where is that scraper you used to de-burr the magazine?” As I retrieved the scraper, D’Arcy mounted the barrel into his lathe; the barrel threads supported by the steady rest instead of running the 3 or 4 jaw due to the iron sights. As the lathe spun the barrel, D’Arcy leaned in wearing his Opti-visors, and very slowly rotated the edge of the scraper on the corner of the chamber mouth, perpendicular to the direction of travel. Little curls of metal began falling, and bright new metal beamed in the light. It took perhaps two minutes – maybe less – to cut a true radius. He polished the chamber mouth with a small piece 180- then 320-grit wet/dry paper followed by a Scotchbright pad, turned off the lathe and removed the barrel, handing it to me. He looked at me from under his Opti-visor. “A radius.” We moved back to the Bridgeport and the Burgess fixture again. He installed a small stub into the action threads and inserted the stub into the receptacle on the left side of the fixture. Then, from the right, he inserted a long tongue through the rear of the action onto the raceways. As he tightened a large screw, the tongue expanded and wedged inside the action, holding it securely. Thus held, the fixture allows the action to swing on a 15” radius horizontally, rotate 360 degrees, and tilt vertically. Genius. “We’ll need to not only adjust the offset to match the taper we just cut in the magazine box, we also need to rotate the action 8 degrees or so to match the original feed well taper above the magazine box. All these angles and related geometry direct the rounds coming out of the magazine, through the rails, up the bullet ramp and into the chamber.” “Where does the 8-degree measurement come from?” I asked. “Measure enough Mausers and you’ll see that number pop up time after time. It seems to work quite well for most applications.” (This was confirmed after I arrived back home when D’Arcy forwarded me one of Jim Wisner’s incredibly informative emails on converting a standard Mauser 98 to .404 Jeffery. Jim relates that of all the actions he has measured [and one can presume that is a LOT of actions], all of the angles were between 6 and 10 degrees, with 8 degrees working the best.) To offset the fixture the correct amount, D’Arcy referred back to the worksheet he prepared for me – more math. I didn’t quite understand the formula, but I did catch on to the big, bold text that read: .992 gage block. We placed several steel gage blocks that totaled .992 on the rear deck of the fixture, swung the arm to meet them then tightened it snug. D’Arcy then stacked a 5-degree and 3-degree block together on the underside of the action and placed a precision level on the top. He rotated the action until the level zeroed, then tightened the stub end-of the fixture. He checked the existing of the feed well radius as it transitioned into the feed lips with a radius gage (Note to self: the number of gages of all types required for this work is staggering), grabbed the corresponding a 1/4” carbide ball end mill and installed it into the spindle. Wayne Jacobson once referred to a CZ 550 action as being as “hard as a whore’s heart.” This FN action must have been her twin sister. Still, the cutter began to do its work, as progressively more and more metal fell onto the table. The vertical depth of cut was also increased in what looked like .100 deeper with each new pass. As we cut the 8-degree taper into the well of the action by .005” or so at a time, D’Arcy dropped the cutter incrementally into the action until the new radius blended into the original FN contour After one side was complete, we mirrored the work on the other side, and then, as we had with the magazine box, enlarged the neck and bullet nose area in the forward part of the feed well for clearance. If all the math added up right, when the magazine box was installed to the action, the inside of both the magazine box and the action’s feed well would match. They did seamlessly with the exception of the original relief cuts in the feed well that served the same purpose as in the magazine box. Millwork complete, D’Arcy mounted the action in a bench vise by the barrel stub and set to the freshly cut feed well with a rotary grinder, special contoured stones, and the ever-present wet/dry paper. When he was finished, he flipped the action over into the vise, handed me the rotary grinder, stones and paper, gave me few bits of instruction and said, “Now, make this side look like the other side.” Panic. “And go easy with that grinder – it removes a LOT of metal.”  I had concentrated hard before, but it had been a long time since I concentrated this hard on a physical task. At each swipe of the grinder on the action, the thought ran through my head, “Did I just ruin it?” Eventually it seemed I had taken enough metal off to transition to working by hand, and it was a welcome relief. Once I felt the two sides matched, I called D’Arcy over for inspection. He dropped his Opti-visors down over his glasses and looked closely, running his fingers across the feed well. “Looks like you got a little heavy-handed here,” he said, pointing to a slight depression midway on the rail. I smiled a cheesy smile. “But it’ll work just fine.” The final, major piece of work on the action was the feed ramp. This was not to be left to the hands of an amateur, so while D’Arcy worked on that, I got set up on the other end of the bench with the extractor. It took a bit too much force to snap the extractor into the case’s groove (which caused the round to stay in the magazine box too long), and with a light touch with a diamond hone, I eased back the lower edge of the hook, all the while keeping the face profile consistent. We also cut a slight angle on the back side of the hook and polished the edge to help guide it easily into the groove without balking. We confirmed the correct amount of extractor tension on the case’s extractor groove by mounting the bolt into the vise on the mill and using a dial indicator to measure the deflection of the extractor as the case was snapped into place. .005” of deflection held the case firmly and would allow the Claw System to work as designed. Apparently not all manufactures maintain the same OD for the extractor groove. Too small a diameter on the groove spec can render a the claw as useless as lipstick on a pig while a grove much larger than the extractor is set up for can cause the feeding issues. Ideally you set up any claw extractor for the brass you intend to use. I had chosen Lapua, so felt confident all my brass would function as this one did. The feed ramp work consisted of essentially blending the two existing angles of the FN into a singular blended convex radial surface, and also widening it in anticipation of the flat-nosed bullets we knew we would try to get to feed. There is little more I can add on this operation since there were no gauges or tools used other than the rotary grinder and eventually hand files. It was D’Arcy’s 40 years of experience that guided this work. Part the Sixth It was time to check the feeding. For those of you keeping time, it was 8:42am on February 11 when the action was again screwed on to the barrel and we began to really see how the thing fed. We started the work the previous day at 7:30am and didn’t walk out of the shop (and into a blowing snow storm) until 9pm. This day started at 7:11am and a hard time window meant we had to be finished at 3pm. Like The Bandit, we had a long way to go and a short time to get there. D’Arcy has been quoted as saying, “Everyone can finish a rifle to 90%, that’s not all that difficult. It’s the last 10% of any project that is most often neglected.” We were now at the last 10% of this project. D’Arcy attached the magazine, being careful to leave the appropriate .040”, or a 1mm gap between the bottom of the receiver and top of the magazine, loaded up the dummies with the North Fork Cup Point, shot me a glance, and began to cycle the bolt. To my utter surprise (but not his) they fed. No, it wasn’t (yet) perfect, but fed they did. You’ll recall at the start of this project, the same North Fork Cup Point deftly jammed against the upper part of the H-ring; these never cleared the feed rails at all. We were close, very close. I wish I could relate all of the fine bits of work that went into this final step of putting the parts of the System 98 to work to accomplish perfect feeding, but it’s difficult. The over-arching process here was to watch how the bullet initially contacted, then traveled up the feed ramp until it exited, while at the same time noting when and how the case was guided out from under the rail as the case groove snapped under the extractor, the case seated fully, and was pushed into the chamber. It’s unavoidable, but trial and error and a hell of a lot of experience are the tools of the trade here. As D’Arcy predicted, the flat-nose bullets caused the biggest problem. Due to the design of the large meplat, solids hit the bullet ramp at a much lower position and farther to the left and right of the centerline on the bullet ramp than a traditional FMJ. When driven at speed, they bounce and/or ricochet off the ramp at a much steeper angle on their way toward the chamber mouth. They also have a tendency to hang on the small shoulders at the corners of the ramp, causing a hiccup in forward motion. With the aforementioned rotary grinder, he re-shaped these corners, and we tried the dummies again. More shaping, more testing. If there were a positive note on these flat-nosed bullets, it was their composition left a distinct bronze- colored track on the feed ramp, so it was relatively easy to see exactly where the bullets hit. During this process, we noticed that the base of the dummy had a tendency to remain too low in the magazine, occasionally allowing the bolt to over-ride it. D’Arcy removed the follower and magazine, setting them on the bench in the same vertical orientation they were in the magazine box. Keeping the follower level, he pushed down very slowly, watching how the spring collapsed. Sure enough, as he pushed the follower down, and after about ¼ of its vertical travel, the rear of the follower dipped, while the front stayed up. This meant that the spring rate throughout the vertical travel of the follower was not consistent; there was a “weak” spot during its travel. “Easy enough,” I thought, we’ll just grab another spring. About 20 springs and 30 minutes later, D’Arcy found a spring he felt was up to the task and the feed work commenced. The rear end of the case no longer dipped. Problem solved. I don’t know how many dummies we ran through the thing, but, with a little more shaping on those corners of the ramp to accommodate the Cup Points, we had them, the Woodleigh 286gr, and the North Fork 286gr SP feeding along the same track and cleanly into the chamber; we were home free – or so we thought. We were feeling good, when D’Arcy said, “Where are those A-Frames?” He loaded one into the chamber, and slowly pushed the bolt forward. It seemed to track like it should, and he pulled the bolt back, reinserted the dummy in the magazine for a full-speed test. The he slammed the bolt home with authority, just like he had been doing this whole time, but the bolt stopped – it would not rotate closed. What the hell? I checked the OAL of the dummy, it was a few thousandths shorter than the North Forks – and it was crimped in the cannelure. Huh? Many short four-letter words, a deadblow hammer to remove the bolt (along with the case), and a long cleaning rod to eject the bullet from the lands later, we had the answer. The 300gr A-Frames are very front heavy, and we suspected (and confirmed after I arrived home) they start life as a 300gr .375 and are swaged down to 9.3. The cannelure is not correctly positioned for this bullets. It might work with an original C.I.P throat and leade, but not with the geometry that I had in my chamber. Black lines indicates approximately where the bullet hits the lands. L-R 250gr Barnes TTSX, 300gr A-Frame, 286gr North Fork, 286gr Woodleigh SP, 250gr Woodleigh RN, 286gr North Fork Cup Point, 286gr Barnes Solid “We're in short grass now,” D’Arcy said. And good thing too, as it was approaching 3pm and our hard time window was closing. We cleaned up the action, reassembled the rifle into its stock and for good measure, ran more dummies through it. They all fed perfectly, no matter which style was loaded where, and ejected them all into a nice little neat pile on the bench. We were both toothy. I packed the rifle, the dummies, and my calipers back into my Pelican case and locked it. D’Arcy drove me back to my hotel where I was to catch the shuttle back to Salt Lake City and my flight home early the next morning. We said our so-longs, shook hands, and D’Arcy drove off as I walked in to the hotel lobby. I arrived at my hotel by the airport at about 7pm and checked in, ready to relax in preparation for the long flight home. I don’t know what everyone else in Salt Lake City, Utah was doing that night of February 12th, but I can guarantee you I was the only one watching Mel Gibson’s Apocalypto and running dummies through his 9.3x62 Mauser. There were no failures. Baxter, You may have no mechanical aptitude but obvoiusly have good film editing skills. That's a great story told through film. I enjoyed watching. Loved the opening titles. Hunting.... it's not everything, it's the only thing. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Great video. D'Arcy is a master. It's nice to see the layout of the shop. Glad you didn't just change out the follower | |||

|

| One of Us |

| |||

|

| One of Us |

I want to see it but it keeps stopping. | |||

|

| one of us |

Excellent! Someone who knows what he is doing. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Thank you, Baxter! Doug Wilhelmi NRA Life Member | |||

|

| one of us |

| |||

|

One of Us |

Baxter, Thank you for posting. I tried to watch it before you placed it on YouTube and couldn't watch more than a few seconds before it stopped and tried to load. I especially enjoyed getting an inside view of D'Arcy's shop. Lee | |||

|

| One of Us |

BaxterB, Thanks for making this and posting it. I laughed, I cried, I craved a gin and tonic. I've got a Husky FN action with that same crest. At least from what I could see. Got me thinking, which is always a bad thing (ask my wife). What cartridge are you cycling through it? I couldn't tell. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Well done Baxter, what cartridge was it? | |||

|

| One of Us |

9.3 x 62 | |||

|

| One of Us |

I couldn't figure out the maker, but I did see the H cut breaching ring on the barrel face. Commercial FN Mauser?? | |||

|

| One of Us |

It is a Swedish crest but the actions were FN; Sweden never made a 98. | |||

|

| One of Us |

As dpcd said, above. Mine's a commercial FN that Husky used from the early 50s.

| |||

|

| One of Us |

Here's a picture of mine:  | |||

|

| One of Us |

Looks quite familiar....;-) | |||

|

| One of Us |

The bottom metal on mine is identical to what you show in the video as well. The steel on the sides is pretty darn thick. | |||

|

| one of us |

Great video. Funny I didn't have to do anything but change the follower, but of course mine is a Bob. Have gun- Will travel The value of a trophy is computed directly in terms of personal investment in its acquisition. Robert Ruark | |||

|

| one of us |

Great video. Enjoyed getting a peek in D'Arcy's shop. His lathe is a brother to mine, 5900 series Clausing. Looks like a Hoeing stock duplicator ! He must have a heck of a dust collector to run it in the middle of the shop ? Craftsman | |||

|

| one of us |

Glad you guys got it working and it didn't make its way over the fence into the retention pond. | |||

|

| One of Us |

There was a moment I thought it was...i swear I heard him mutter under his breath, “where’s the hacksaw?” | |||

|

| one of us |

I've seen that movie! You guys made my day with that phone call. | |||

|

| One of Us |

BaxterB,thanks for sharing a craftsman at work. Great video. jc | |||

|

| One of Us |

Sometimes it’s good to know you don’t suffer such frustrations in solitude... ;-) | |||

|

| One of Us |

The music was a huge annoying distraction for me. Simple clear narration would have been much-much better. I had to turn it off and move on. | |||

|

| new member |

Thank you very much! Is the windex next to the action vise and barrel wrench for some purpose other than cleaning windows? | |||

|

| One of Us |

Two Days with D'Arcy Echols, one of best contemporary gunsmiths and all you could post is 3 minutes of video minus a bunch of fade in/outs? I appreciate the effort you put into this but it would be nice if you could add more substance (like the rules we followed) and less,,,, well creative videography. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Everyone is a critic. And forgot to read the last line of the first post. | |||

|

| One of Us |

I know D'Arcy does a great job at this, but the video seems to show the feeding before D'Arcy is finished working on it. The last round at the end of the video isn't in the correct spot before the bolt pushes it home. The case head is way too low. I'm surprised the bolt didn't override the cartridge. Again, I'm sure the end of the video isn't the end of the feeding work performed by D'Arcy. | |||

|

| One of Us |

James, you are 100% correct. I actually think that was the first or second time we ran the dummies through. The video is merely for dramatic effect.. :-) | |||

|

| One of Us |

Looks like it might have had the wrong follower in it. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Good one! But no... :-) | |||

|

| One of Us |

My apologies, I probably jumped right over it cutting to the chase. Thanks for filling in the details!!!!! | |||

|

| One of Us |

Full report and pics added - thanks to 30.06king for allowing me to poach his post for the second half! | |||

|

| One of Us |

No worries Baxter. More than happy to help. Definitely worth it for your great narrative. Hunting.... it's not everything, it's the only thing. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Thanks Baxter! | |||

|

| one of us |

Ive seen a number of D'Arecys rifles in Safari camp over the years, and they all worked slicker n snot.. I have seen a lot of well known custom rifles that failed to feed, and I mean a lot by well known and unknown smiths..Its an art form for sure..I hear all the horror stories in my booking business..The other thing Ive seen a lot of is stocks splitting out, some were beautifully bedded also..I decided for a hunting rifle a glass bedding that does not show and is like a thin coat of paint, and two cross bolts is good insurance..as is the old fashion forend screw ala pre war and early mod. 70s.. Ray Atkinson Atkinson Hunting Adventures 10 Ward Lane, Filer, Idaho, 83328 208-731-4120 rayatkinsonhunting@gmail.com | |||

|

| One of Us |

All very good. What I don't understand is all that wide open floor space!! Cheers, George "Gun Control is NOT about Guns' "It's about Control!!" Join the NRA today!" LM: NRA, DAV, George L. Dwight | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Guns, Politics, Gunsmithing & Reloading

Guns, Politics, Gunsmithing & Reloading  Gunsmithing

Gunsmithing  (Complete Report and Pics 3/11!) Two Days with D'Arcy Echols - Making a Mauser Feed

(Complete Report and Pics 3/11!) Two Days with D'Arcy Echols - Making a Mauser Feed

Visit our on-line store for AR Memorabilia