The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Guns, Politics, Gunsmithing & Reloading

Guns, Politics, Gunsmithing & Reloading  Reloading

Reloading  Paper clip check

Paper clip checkGo  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| One of Us |

Back in the day, I was taught to use a paper clip to check the inside wall of a cartridge case at the juncture of the case body and head. The idea was to straighten a paperclip, bend ⅛ inch of the tip to 90 degrees, and then feel for a groove at that juncture, which was supposed to indicate incipient case head separation. I routinely include that process to this day when I inspect cartridge cases prior to reloading. In all this time, I've found only one case with that little groove, but I'm glad I found it. Is there anyone else who does this? | ||

|

| One of Us |

I do this as well. Tom Z NRA Life Member | |||

|

| One of Us |

| |||

|

| One of Us |

There is also normally at the same time a dull ring on the out side showing the case has stretched. If I see this,I do use a dental tool and you will feel the "divot" on the inside of the case as well. It can really be felt on the belted magnum cases. Gulf of Tonkin Yacht Club NRA Endowment Member President NM MILSURPS | |||

|

| One of Us |

I use the sharpened and bent paper clip on cases showing the ring outside and also on any I am not sure of. I don't routinely do it as part of case prep though. PA Bear Hunter, NRA Benefactor | |||

|

| One of Us |

I do not bother with it; I make sure my brass (I ignore belts and make them headspace on the shoulder) fits the chambers snugly so it does not stretch. Better to work in front of the issue than at the back end. It is too late then to do anything about it. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Agreed . . . but what criteria do you use to remove a case from service? | |||

|

| One of Us |

Slamfire, I've never seen anything like that, but I wonder if what happens in an M1A (or any semi-auto) is a good model for bolt action rifles. Mind you, I don't know that it isn't an appropriate model, but I'd be more impressed if this had happened in a bolt action. | |||

|

| One of Us |

| |||

|

| One of Us |

Cool Gruff. I have to make up one of those now too. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Some of my Magnums have a bright ring above the belt. I checked them with the paper clip and even sectioned a few cases and could find no indication of separation. Still I only shoot a limited amount of hotter loads through them. What do you guys do? | |||

|

| One of Us |

+1 Tricks like this is why I love this forum. Or at least, one of the reasons. Thanks. | |||

|

| One of Us |

My brass gets removed from service when it gets lost or is not longer reloadable. I do have a #4 Enfield that eats brass; they stretch and separate after about 4 loadings. (Enfields are noted for stretching brass). You can usually tell when they are ready to go, but if they separate; it is no big deal; I don't hunt with it. BL; if that happens in any rifle, it means your brass is too short for the chamber; or if rimmed, the rim is too thin (headspace is too big in the rifle). Easy to fix if you make the brass a tight fit on the shoulder. Also, it might mean that the action is "(springing" which in the case of a rear locking thing like the #4, it might be. Tex, that bright ring can be from re-sizing too; if you aren't getting any inside thinning then you are ok. Worse case; you have stretching and you then re-size the shoulder back down; next firing; it will do the same thing until; you get a head separation. If you get a slight stretch the first time, but from then on, don't FL size it, then it won't stretch any more. Unless it was the action "stretch" that caused it in the first place. Then you are SOL and have to live with it. Or reduce your loads. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Another thing to consider; I load for mostly big bores and double rifle cartridges, which tend to operate are relatively low pressures and don't tend to stretch cases. When I load for high pressure stuff, I make damn sure the brass fits tightly with a bolt close "feel", except for ammo I use for hunting, in which case, easy chambering and reliability is paramount. | |||

|

| One of Us |

+1 to both the above. . | |||

|

| One of Us |

Do not confuse the joint of the case head as the ring that indicates potential separation. The impending case separation ring is further up the body of the case where the brass is thinnest; 223 are about 1/4" - 3/8" from the base; 30-06 about 1/2" up from the bases. PA Bear Hunter, NRA Benefactor | |||

|

| One of Us |

Thanks dpcd. What you say makes sense. I'd not thought of things quite that way. Plus, I'd always had in the back of my mind why, other than inconvenience, a simple head separation might be so dreaded. | |||

|

| one of us |

I use a dental pick they come in all shapes and most dentist will give you one..Its never too late to toss a case, if I feel a cut its in the dump, same with loose primers when I seat them, the loose ones go..case inspection ain't a bad idea. I have in some cases seen the cut from the outside of the case also, so visual inspection is a plus..and yes on rare occasions you can expect to blow a case in half and most of the time its just a problem, sometimes its a wake up call and scary as hell. Ray Atkinson Atkinson Hunting Adventures 10 Ward Lane, Filer, Idaho, 83328 208-731-4120 rayatkinsonhunting@gmail.com | |||

|

| One of Us |

Thanks dpcd, Jtx and Ray. What I do as well is never trim but once after the intial sizing and trimming. If the case needs a second trim then I pretty much know that it has grown more and is thinning brass. The bright ring on mine could be from sizing as some of my rifles like the Redding FL sized brass in spite of the fact that I have the bushing die too. I also haven't used the Willis die on these cases - but I might give that a try too. The bright spot shows sometimes by the second loading - so it still is something for me to keep an eye on as most of my loads are up in the near book max area. | |||

|

| One of Us |

I have done the same thing for years. My tool is a piece of coat hanger wire bent at a right angle and sharpened. Works good for me and the price was right. NRA Patron member | |||

|

| one of us |

All fired rifle brass will show a pressure ring in front of the case head about a quarter to three-eighths of an inch. This is where the brass becomes thick enough that it will not yield to the internal pressure and resists being expanded against the chamber wall. Such a pressure ring is normal and the higher the pressure of the load the more visible it is -- even after only a single firing. This pressure ring is ALSO the point at which the brass stretches when the headspace is slightly long (as is always the case, to one degree or another, with unfired brass or factory ammunition). If the case is sized excessively, it will stretch again in this same place. Successive resizing and firing will cause the brass wall at the pressure ring to become so thin as to crack, or sometimes even completely separate the head from the case. Using the bent clip or pick allows you to determine if a case has developed significant thinning and should be discarded. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Gas guns are more severe on brass because they designed to unlock when there still is residual pressure in the barrel. Sidewall necking occurs sooner with gas guns than bolt rifles, assuming reasonable shoulder set back for both. In either action, with a dry case and a dry chamber the front of the case adheres to the chamber, fixing the cartridge location. Usually there is a gap between the base and bolt face, which is the distance the case shoulder was pushed back, and as it turns out, the back of the case stretches until the base reaches the bolt face. If the case shoulder is shoved too far back for either action, sidewall necking will occur, and just how much sidewall necking occurs depends on the initial excessive headspace between case and chamber. For gas guns, there is additional sidewall stretching during the residual blowback period. Of course, this is assuming a dry case and a dry chamber. For my 30-06 and 308 gas guns I shoot lubricated cases. Instead of adhering to the chamber, the cases slide to the bolt face, taking up the headspace, the shoulders fold out in front, and the back does not get stretched. I don't get sidewall stretching and I don't get case head separations. These are 308 LC cases I fired in my Supermatch M1a. The letter R stands for the number of times reloaded, R5 would be reloaded five times. I have cases which developed case neck cracks and body splits, and I sectioned them. The case labeled R22 was fired 23 times as a lubricated case. There is absolutely no evidence of any case head separation due to sidewall stretching.   First time I fire bolt gun cases, I lubricate cases, especially for belted magnums, where the base to shoulder distance is not standardized. 300 H&H magnum cases are around $2.00 and up, so I don't want excessive, life time reducing, sidewall stretch on the first firing. After first firing I set the shoulder back around 0.003" and case life is excellent. These are examples of what happens when you set the shoulder too far back and fire the case in a bolt gun. These are not my cases. My photo notes indicate this came from a 6.5 Creedmoore bolt gun.   These are cases from a 300 WSM bolt rifle.   | |||

|

| One of Us |

Slam — thanks. Pure gold. | |||

|

| One of Us |

That is an excellent point; lubed cases won't ever separate due to the reasons stated above. If the front, ductile part of the brass can't adhere to the chamber walls, then the whole case will slide back against the bolt face. That is how the British used to measure pressure; axially, not radially like we did/do. One thing to keep in mind though, is that transmits the maximum pressure to the bolt lugs; dry cases and chambers limit that quite a bit. Just make you do it in good modern rifles and not soft ones. Or doubles. | |||

|

| One of Us |

The British, nay, the Continental system proof system is well engineered, well thought out and has a lot to recommend it. When the proof house stamps its name on the action, its reputation is at stake, not the reputation of the manufacturer. Proof houses have to provide the user something more than the manufacturer, and that something is assurance of quality. Therefore it makes total sense that a Proof House would use a system that eliminates parasitic frictional losses and fully loads the action. Any test method that does not fully load the structure will not provide results or confidence that the structure was adequately designed or manufactured. In my opinion, the American test technique is lacking in credibility. It does not fully load the locking mechanism. American manufacturers just want to get the thing out the door, their "proof" tests are function and quality control tests, not tests that stress the design. If any problems occur later, American manufacturer's cover it by warranty. In the old German proof standards, if the firearm did not pass proof, it was returned smashed, cut into pieces, but otherwise destroyed. The consumer therefore had more assurance that the item was good, because it passed a test of high standards.

I develop my loads with lubricated cases because I am of the opinion that the friction between case and chamber will disguise over pressure loads by lowering the amount of case thrust transmitted to the bolt face. I want to feel a sticky bolt lift when I get there. I have read a number of accounts where people got a little oil, a little grease on their case, and complained about pressure signs. Well guess what, their loads were overpressure to begin with and friction between the case and chamber disguised their problem. They accidentally removed the parasitic friction and the problem was revealed. If someone is having pressure issues in a double rifle because their case is slick, the absolute first thing they should do is cut their loads! It is a poor mechanical engineer who designs his system to fail at less than the maximum rated load. I have measured the shear on the Mauser, 03 Springfield and it is plainly evident to me, that the designers of these actions knew what they were doing, and the actions are designed to withstand tens of thousands of load cycles that assumed case friction was zero. The idea that this thin brass tube was designed to reduce the load off what is, 1/2" shear thickness of tempered steel, is laughable in the extreme.  When you make the case carry load, you damage the case. The case is not a structural element, it should not carry load, it is the weakest link, and the action is there to support the case, not the other way around. This is worth repeating: The action is there to support the case, not the other way around. You must use loads that are appropriate for the action. Older actions were made out of inferior materials and made under primitive process controls. They also operated at pressures that are lower than what people expect. Rifle & Carbine 98: M98 Firearms of the German Army from 1898 to 1918 Dieter Page 103. M98 Mauser service rifles underwent a 2 round proof at 4,000 atm gas pressure, 1 atm = 14.6 psi, 4000 atm = 58, 784 psia. Gun Digest 1975 A History of Proof Marks, Gun Proof in German” by Lee Kennett. “The problem of smokeless proof was posed in a dramatic way by the Model 1888 and it commercial derivates. In this particular case a solution was sought in the decree of 23 July 1893. This provided that such rifles be proved with a government smokeless powder known as the “4,000 atmosphere powder”, proof pressure was 4,000 metric atmospheres or 58,000 psia. Unless someone can produce credible data as to the design limits used by Paul Mauser, I am going to state that it is reasonable that the early Mauser action was designed to support cartridges of 43, 371 psia with a case head diameter of 0.470”, and that pressure limit should be adhered to in loading for early Mauser actions. No one should expect that they can jack up the pressure of their load and expect case friction to save them from the effects of overloading the action. Salesmen of such ideas, like P.O Ackley, are selling snake oil. The load did not go away, it is being carried somewhere else, typically the barrel and the case, and overpressure loads will reduce their fatigue life just as much as overpressure loads will reduce the fatigue life of receiver lugs. If someone is having pressure problems with their double rifle, old military rifle, or modern rifle, the absolute first thing to do is cut your loads! | |||

|

| One of Us |

I agree with the Mauser pressure figures. We test (not mandated by the govt) on a radial basis because that is where the largest surface area for the pressure to act upon, is and back in the days before chrome moly steel, that is where the failures were. No more. Force transmitted directly to the bolt face, even on an oiled case, is small compared to the surface area of a chamber. Any modern action will take the few thousand pounds of force that is transmitted to it by the chamber pressure; you prove that by your oiled cases. You are right, don't depend on case friction to mitigate effects of heavy loads. Any rifle action is designed to hold in worse case scenarios; when the case head fails, which they did in the early days. And tens of thousands of rounds, although some of them can't do that, like 93 Spanish Mausers. Too soft for even the light 7mms ammo. I still do not recommend to anyone to use oiled cases. Although on our M60A1 tanks, when we had the M219 machine guns, oiling the ammo was the only way to keep them firing; they were pieces of crap. When we got the FN, M240s that was like driving a new car. | |||

|

| One of Us |

If I remember correctly, the Japanese lubricated their machine gun ammo during WW2. Thanks to you and Slam for schooling me (and I'd bet a bunch of other folks, too). I just keep on learning. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Yes, but oiled ammo in combat is always a bad idea due to the carrying of dirt and carbon into the chamber. Thanks for for vote of confidence but I make most of it up as I type. | |||

|

| One of Us |

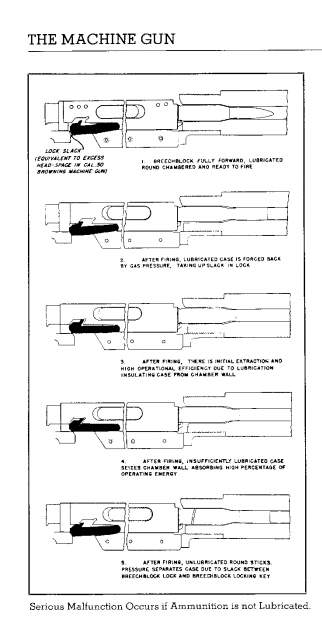

The use of greases, oils, and “waxes” to provide cartridge lubrication was well known to designers prior to WW2. Melvin Johnson, the inventor of the Johnson rifle, was aware of the use of these in small arms: Army Ordnance Oct 1936: What Price Automatic?, by Melvin M. Johnson, Jr. Several methods have been devised to retard the unlocking of the block or bolt mechanically. The most appealing point in such a system is consolidation of the “automatic” parts in the breech. However, there is one serious difficulty. The conventional cartridge case does not lend itself to such a system unless adequate lubrication is provided, such as grease or wax or oil on the cases or in the chamber Thus, the Schwarzlose machine gun has an automatic oil pump: the caliber 30 Thompson rifle (not the caliber 45 T.S.-M.G.) had oil pad in the magazine, and special “wax” was needed on the cases designed to be used in the Pedersen rifle. Literally billions of oiled cartridges were fired in machines guns. General Hatcher was well aware of the use of greased cartridges and oiled cartridges: Army Ordnance Magazine, March-April 1933 Automatic Firearms, Mechanical Principles used in the various types , by J. S. Hatcher. Chief Smalls Arms Division Washington DC. Retarded Blow-back Mechanism……………………….. There is one queer thing, however, that is common to almost all blow-back and retarded blow-back guns, and that is that there is a tendency to rupture the cartridges unless they are lubricated. This is because the moment the explosion occurs the thin front end of the cartridge case swells up from the internal pressure and tightly grips the walls of the chamber. Cartridge cases are made with a strong solid brass head a thick wall near the rear end, but the wall tapers in thickness until the front end is quiet thin so that it will expand under pressure of the explosion and seal the chamber against the escape of gas to the rear. When the gun is fired the thin front section expands as intended and tightly grips the walls of the chamber, while the thick rear portion does not expand enough to produce serious friction. The same pressure that operates to expand the walls of the case laterally, also pushes back with the force of fifty thousand pounds to the square inch on the head of the cartridge, and the whole cartridge being made of elastic brass stretches to the rear and , in effect, give the breech block a sharp blow with starts it backward. The front end of the cartridge being tightly held by the friction against the walls of the chamber, and the rear end being free to move back in this manner under the internal pressure, either one of two things will happen. In the first case, the breech block and the head of the cartridge may continue to move back, tearing the cartridge in two and leaving the front end tightly stuck in the chamber; or, if the breech block is sufficiently retarded so that it does not allow a very violent backward motion, the result may simply be that the breech block moves back a short distance and the jerk of the extractor on the cartridge case stops it, and the gun will not operate. However this difficultly can be overcome entirely by lubricating the cartridges in some way. In the Schwarzlose machine gun there is a little pump installed in the mechanism which squirts a single drop of oil into the chamber each time the breech block goes back. In the Thompson Auto-rifle there are oil-soaked pads in the magazine which contains the cartridges. In the Pedersen semiautomatic rifle the lubrication is taken care of by coating the cartridges with a light film of wax. Blish Principle….There is no doubt that this mechanism can be made to operate as described, provided the cartridge are lubricated, …. That this type of mechanism actually opens while there is still considerable pressure in the cartridge case is evident from the fact that the gun does not operate satisfactorily unless the cartridges are lubricated. Thompson Sub-Machine Gun: … Owing to the low pressure involved in the pistol cartridge, it is not necessary to lubricate the case. The Hispano-Oerlikon was a blow back cannon, used by the Army and Navy from WW2 all the way through Vietnam. One reference states that 150,000 of the things were made and were in service during WW2. The WW2 era cannons required greased ammunition. Greasing the rounds was a bother, post WW2 an automatic oiler was added, but the historical record of grease use still exists. This grease had to be a “soft” grease. You can see at exactly 2:14 on this WW2 video a Sailor’s hand painting grease on the 20 mm ammunition loading machine for the Oerlikon anti aircraft machine guns. http://www.youtube.com/watch_popup?v=9dR3h2HdnBQ Figure from The Machine Gun Vol V Hispano-Oerlikon page 358 http://www.milsurps.com/conten...y-George-M.-Chinn%29  There were problems if the grease film was inadequate: http://hnsa.org/doc/gun20mm/part4.htm ORDNANCE PAMPHLET NO. 911 March 1943 GREASING AMMUNITION All 20 mm. A.A. Mark 2 and Mark 4 ammunition MUST BE COMPLETELY COVERED WITH A LIGHT COAT OF MINERAL GREASE BEFORE BEING LOADED INTO THE MAGAZINE. The ammunition is usually packed greased. However, this grease tends to dry off. Whether cartridges are packed greased or not, they should be regreased before loading the magazine. NOTE-A small amount of mineral grease, applied shortly before firing, to the cartridge case that is visible in the magazine mouthpiece, will assist in preventing a jam in the gun barrel. Dry ammunition or ammunition with insufficient grease will jam in the gun chamber when fired and extraction will be very difficult, if not impossible. See Page 110 for use of torn cartridge extractor. While I believe in controlling cartridge headspace through the sizing die and cartridge headspace gages, a heavy lubricant may protect the case from excess headspace: The Machine Gun, Vol 1 LTC Chinn, 20mm Hispano-Suiza page 589 http://www.milsurps.com/conten...y-George-M.-Chinn%29 Thus the most vital measurement (headspace) in any automatic weapon was governed by chance in this instance. An unfortunate discovery was that chamber errors in the gun could be corrected for the moment covering the ammunition case with a heavy lubricant. If the chamber was oversize, it served as a fluid fit to make up the deficiency and, if unsafe headspace existed that would result in case rupture if ammunition was fired dry, then the lubricant allowed the cartridge case to slip back at the start of pressure build up, to take up the slack between the breech lock and the breech lock key. Had this method of “quick fix” not been possible, the Navy would have long ago recognized the seriousness of the situation. In fact, this inexcusable method of correction was in use so long that it was becoming accepted as a satisfactory solution of a necessary nuisance. Greasing cases was messy, had to be done before weapon firing, took extra personnel, so post WW2 experiments were conducted to eliminate the grease by using wax, oilers, Teflon coated cases, and even chamber flutes. This is an abstract from a 1954 report. TEST OF TEFLON AND MICROCRYSTALLINE WAX CASE-CHAMBER LUBRICANT APPLIED TO BRASS-CASED 20MM AMMUNITION DIEWERT,JACK R ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND MD Report Date: 01-Dec-1954 This report is on the web: relevant abstracts are below A LABORATORY INVESTIGATION OF CARTRIDGE LUBRICANTS FOR 20MM F.A.T.-16 STEEL CARTRIDGES http://torpedo.nrl.navy.mil/tu/ps/pd...er?dsn=9151649 :In the past decade tests at the Naval Proving Ground had always demonstrated that waxed ammunition was unsatisfactory. Also, it was known that the Army and Air Force had frequently encountered storage and service problems caused by the use of wax on 20MM brass ammunition. Therefore, naval procurement of Army manufactured M21A1 brass ammunition had excluded wax coatings for 20MM cartridge lubrication. Since early in the Korean War it has been naval practice to oil cartridges just prior to use '(reference -(a)). Research at this Laboratory on dry film lubricants for cartridges, began in September 1950. In references (b) and (c), were listed the guides which were to be used in determining the value of a dry lubricant coating for ammunition. The most important conclusion of that investigation was that a thin film of polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) was the most satisfactory dry lubricant coating for cartridges. This conclusion was confirmed in the NRL reports of references (d), (e), (f), (g), (h), (i), and (J). In the past either ceresin wax or microcrystalline wax had been used by the Army as cartridge lubricants. Ammunition storage difficulties with ceresin wax films led the Frankford Arsenal to use a higher melting point microcrystalline wax as an outer coat over the "Case-Cote" varnish. After the Frankford Arsenal learned of the NRL work with Teflon coatings for cartridges, an Army Ordnance project was established at the Proctor Electric Company to put Teflon coatings on the steel F.A.T.-16 cartridges manufactured there. However, certain difficulties arose in obtaining good corrosion resistance with Teflon, apparently due to the manufacturing methods used. Since the use of light oil coatings over Teflon-coated guns has a beneficial effect on rate of fire, it was necessary to repeat the firing tests previously performed on all test ammunition. This resulted in a significant increase in the rates of fire. Thus, oiled brass cartridges averaged 789 rpm, oiled bare steel cartridges averaged 789 rpm, "Case-Cote" wax-lubricated cartridges averaged 820 rpm and Teflon-coated cartridges 810 rpm. However, it should be noted that these high rates of fire are not obtainable on a bare steel gun with oil. It was reported in reference (1) that oil on a Teflon coated gun with properly lubricated ammunition usually produces rates of fire 40-75 rpm higher than normal You can find, if you search, the eventual solution was a weapon mounted oiler. The teflon tests are interesting and I wonder if teflon is being used today on steel case ammunition. I have run into a number of references of "polymer" coated steel case ammunition, and as teflon is a polymer, as well are waxes, oils, greases, etc, it might be that some of these "polymer" coatings in current use are in fact, teflon. | |||

|

| one of us |

A #6 explorer is the dental instrument of most use. muck | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

Visit our on-line store for AR Memorabilia