The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Hunting

Hunting  African Big Game Hunting

African Big Game Hunting  Lukosi Elephant Encounter - Story by Kevin Thomas

Lukosi Elephant Encounter - Story by Kevin ThomasGo  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| One of Us |

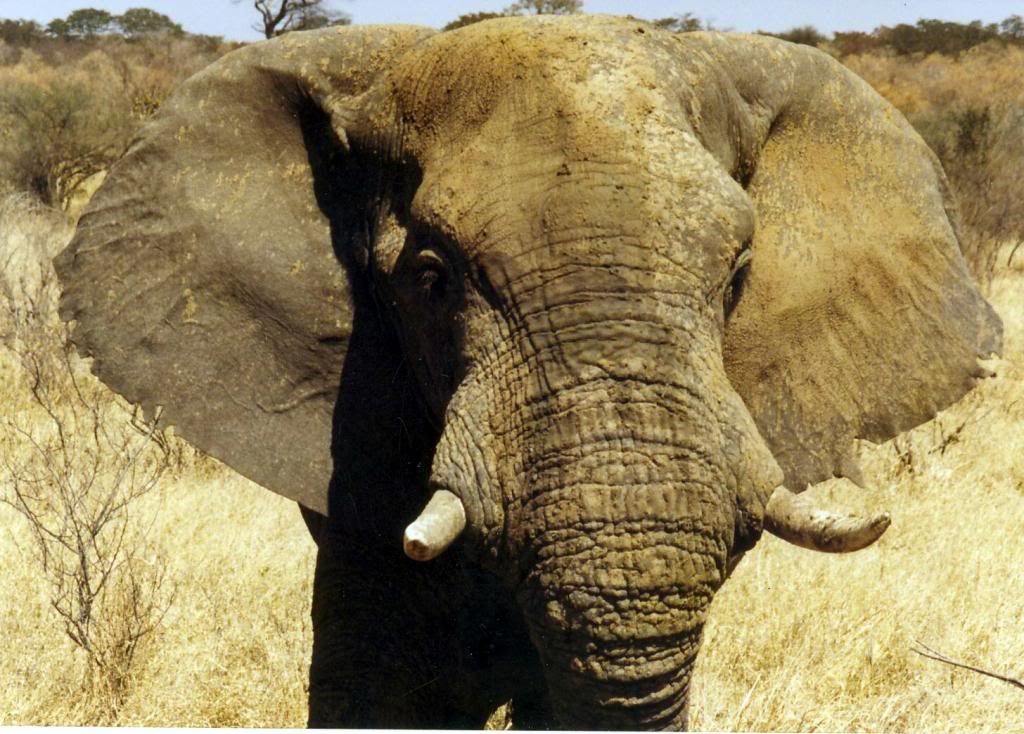

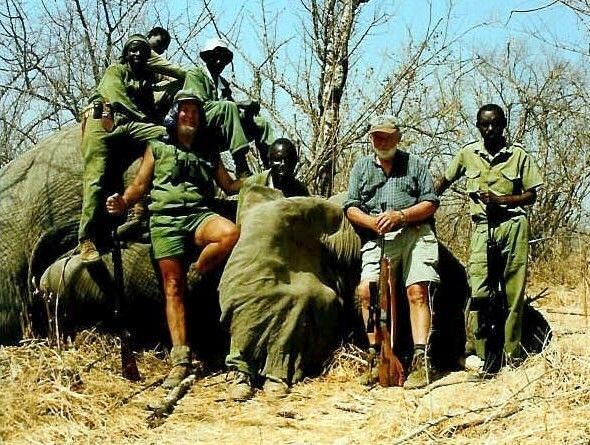

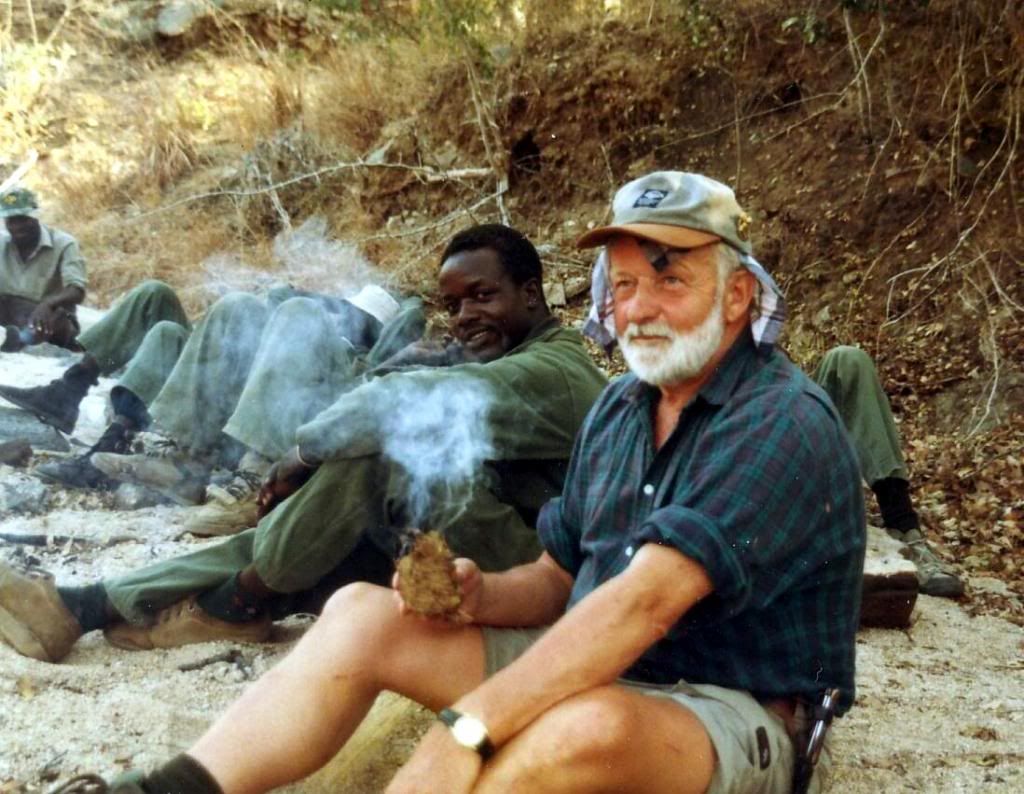

Lukosi Elephant Encounter Kevin Thomas© The vast tract of land lying along the eastern upper reaches of Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park can be energy sapping and it’s a hot and parched landmass to hunt. There are not only tracts of dry mopane woodland, stretching into the hazy distance, but also rock and shale strewn ridge lines and hills covered in thick clingy thorny scrub and thickets of tall yellow grass. On the uneven ridgeline slopes and inside the thorn thickets, visibility is measured in feet rather than yards. As the season progresses towards the furnace hot suicide month of October, one can almost feel the pulse of the heat and humidity. Ultimately it will unleash in violent electric thunder storms, the day darkening perceptively in a still clinging air, before the welcome but normal short duration heavy downpour. This drenching invariably leaves a pleasant scent in the air, a scent unique to Africa – damp dust and dry rain sodden grass. During late August and into September, rain seldom comes to the western part of Zimbabwe, but the heat build up does, and relentlessly so. If a person is negligent, this vicious heat will dehydrate them and punish them badly – heatstroke is to Africa what hypothermia is to the cold climes, and if treated with disdain, will kill you. Thus it was that I found myself hunting during an extremely hot late August with Olaf, who hailed from Norway. He was a WW2 veteran and spoke no English, and his son, who acted as official safari interpreter said his father’s generation had no need to speak English, but never told me why. The Norwegian father and son felt the heat, and for them, exiting the Victoria Falls Airport into outside Africa must have been like walking into an oven. From the airport we drove south through Hwange town, and then, just before we arrived at the Inyantue River Bridge we swung off the black-top, and hitting gravel drove west. The camp and the hunting concession were in what is marked on the topographical maps as State Land V, an area of state land that is sandwiched between the Deka Safari Area and the communal tribal area further east, at the time, Touch Africa Safaris held the hunting rights. My pre-safari scouting of the area had been worrisome – evidence of heavy poaching by neighbouring tribesmen was everywhere. Buffalo sign was old, and no recent movement into the area was evident, elephant and lion came and went as infrequent nomadic visitors from the Deka Safari Area. Although he wasn’t fussy regards the ivory quality, one of Olaf’s safari wants was to experience a bull elephant hunt, and as with all elephant hunting this meant departing camp at first light and looking for viable spoor, and thereafter unless we were lucky would follow hours of physical tracking. Bull elephant in the concession we were hunting were not resident, they were nomadic interlopers from the adjacent Deka Safari Area. Each morning we woke early and departing camp looked for and followed elephant bulls tracks, however, all of them took us to the Deka Safari Area boundary then left us feeling frustrated. The clinging humidity and heat was unmerciful, as were the hordes of persistent sweat bees – so much so that while tracking elephant if we stopped for a five-minute break – we resorted to burning dry elephant dung in the hope that the pungent smoke would drive the sweat bees away. Despite the theory it only seemed to attract more of them. Eventually and on the morning of the penultimate day we were sitting on the edge of a dry millet field, behind us tribal kraals, lowing oxen, bleating goats, Sindebele chatter, and the squeakedy-squeak of a borehole’s pumping arm as the local womenfolk drew water for their domestic needs and saw to the family laundry. The scraggily thorn bushes surrounding the pump were festooned with pastel hued washing drying in the sun, poverty ridden rural Africa in its purist form. Lucky Ndlovu, my erstwhile Ndebele tracker had always thought himself a bit of a playboy and was quick to become involved in some flirtatious banter with the bevy of noisy young women gathered at the borehole, - his ribald remarks soon sending the young Ndebele girls into peels of coy laughter. Despite his lustful thoughts Lucky’s eagle eyes suddenly narrowed and pointing with his demo (traditional axe) towards a far bread-loaf shaped hill, grey and out of focus in the shimmering heat haze, he excitedly remarked in the vernacular, “Khangela indlovu” (Look elephant) It took the use of binoculars for me to pick up the line of seven bull elephant slowly climbing the hill along a narrow game trail. From where we were they looked like blobs of grey slow moving window putty. They were just west of the road that leads from the colliery town of Hwange, to Sinamatella Camp inside the National Park. Quickly returning to the hunting rig we made our way towards the hill feature, it was close to midday and the elephant were clearly headed to the top of the feature for a bit of siesta. During the early hours they had obviously crossed the route we now followed, for spread across the old millet fields their tracks were everywhere, masticated millet stalks and chewed mopane branches helping to indicate their route towards the high ground. After crossing the gravel Sinamatella road the wind wasn’t in our favour anymore so from where we left the vehicle in the care of one of the crew, we continued on foot round the hill feature and eventually reached the north-western side. After looking at how dense the tangled jesse thickets were on the lower slopes, and the limited visibility they afforded, I removed my .375 H&H cartridge belt and handed both it and my .375 rifle to Lucky. He in turn handed me my .458 Winchester cartridge belt and my .458 Winch – as things turned out, it was a wise move – the heavier calibre’s much needed stopping power saving the day. Our planned strategy was simple; we would summit the flat topped feature then quietly move into the wind, continuing through the thickets, until we had located the resting elephant. We climbed slowly, the heat was stifling and there was no respite from persistent sweat bees. In a day-pack on the one tracker’s back were some full water bottles and each time we stopped we slaked our thirst, bringing welcome relief to parched mouths and throats. All around us it was deathly quiet, as if clinically sanitised, with not a sign of life. No birds, no insects, no nothing – just heat, jesse thickets, and smoky haze. Once on top of the feature we moved Indian file through the thicket, visibility was mere paces, and tangled hanging branches hooked our clothing despite our following a well used myriad of elephant paths. Eventually and somewhat surprisingly the thicket began to thin out, and open up – and it was then that we heard the first tell-tale indication of resting elephant – the leathery whack of enormous ears fanning, brief gurgling flatulence, then a branch snapping. Glancing at Olaf I noticed that he was keyed up, where he was gripping his rifle his knuckles were white. We kept moving forward silently until we actually saw one of the elephant and at that stage I indicated to the council game scout and another arbitrary official hanger-on to remain where they were. Careful searching showed another two elephant standing quietly amongst the clumps of jesse. They weren’t gathered in a group and were spread out line abreast, of those we initially saw none had ivory worth a second glance; they were seemingly all middle-aged and young bulls carrying very small tusks. With Olaf and Lucky accompanying me and the wind still in our favour we moved quietly along the line of elephant. It didn’t take long to account for all of them and with it being more of an elephant hunt experience, than a quest for trophy ivory as such, and with time against us, I decided to let Olaf shoot the bull second from the extreme right. To this elephant’s left was a fidgety young bull, probably not yet 20 years old, who was playfully breaking saplings but also moving diagonally albeit slowly towards our immediate right flank, I guessed that if he continued, he would end up passing us from about six paces and end up downwind of us - if that happened, he would immediately scent us. Quickly grasping Olaf by his right bicep I moved him up to a position directly in front of the bull I had in mind – Olaf shot well and this despite his tendency to excitement – which happens too many of us, so I felt he would handle a frontal brain shot without a problem. When we were between about 15 and 20 paces to the elephant’s front, I indicated to Olaf to do the deed as I simultaneously brought my rifle hard into my shoulder. Out the corner of my eye I observed Lucky Ndlovu turning and quietly starting to move away from what was about to unfold – and unfold it certainly did – with alarming if not frightening speed. In the final few seconds prior to the shot, the elephant suddenly seemed to sense that all was not well and raising his head in typical “elephant standing tall” mode tried to make out what it was to his immediate front that had roused his suspicions. Glancing to my right I noted that the younger bull, still totally unawares of us, was almost on top of our position and that Lucky was starting to panic, and in doing so had allowed his discipline to slip. The tracker’s movements to the right - and behind Olaf and I - had attracted the target elephant bull’s attention. Waiting for Olaf to shoot and watching the young elephant bull arriving at the very place where we were standing had unnerved the tracker. It was as this slight jesse bush drama was being played out that Olaf fired at the bull, but his bullet went way low of where it should have gone. Never in my entire game ranging or professional hunting career had I envisaged that an elephant was capable of such acceleration. From stationary curiosity to full speed he would have made a cheetah look like a geriatric tortoise. It was not a charge at all, rather, a panicked blind rush straight at us following the impact of the badly placed bullet (under such circumstances, it’s normal for an elephant to take off in the direction it is facing), a rush that would have seen him flatten Olaf and me – permanently – had the only shot I was literally just able to snap off not found its mark. The impact of the 500grn solid crumbled him, but such was his forward momentum that when he went down, his front legs and feet ended up under his stomach and firmly wedged between his hind legs – with his hindquarters somewhat elevated. Although the elephant was dead as he hit the ground, I was impressed that in those split seconds, Olaf had managed to run another shell into the chamber and get off a quick second shot although it passed straight through the elephant’s outspread right ear. In the immediate aftermath and as the dust settled, it was a relief to observe that the bull had dropped at about four normal paces to our front. When Lucky sheepishly returned after having dodged the other fleeing elephant, I pointed at my trusty .375 H&H he was clutching and reminded him that had we not swapped rifles when entering the jesse thickets, Olaf and me may have gone out of there as stretcher cases (if lucky) – although more probably in body bags. My firm belief in always carrying a rifle capable of delivering a minimum of 400grns of solid in the thick stuff is unchanged. There is no doubt the proven .375 H&H would have done the job, but such was the majestic beast’s momentum he might have run us over before going down. He had to literally be stopped dead in his tracks – and if correctly placed – only a minimum of 400grns of solid will do that – and although I ultimately changed to a .458 Lott, during that close encounter the .458 Winchester had stepped up to the plate admirably, and I have every faith in it. Later during the day, while we were cutting the elephant up an old tribal elder arrived on the hilltop, he was smartly dressed in long pants and a well-pressed shirt, and after paying us the customary greetings, he stated in a matter of fact way, “Last night Princess Diana of England was killed in a car crash” it was 01 September 1997, and the first we’d heard of it. He then told us he’d come to convey the message, and could he please have some elephant meat! We obliged.  Looking west across State Land V from the Touch Africa Safaris camp near the Lukosi River in 1997.  Touch Africa Safaris tented camp was comfortably appointed.  … meant departing camp at first light and looking for viable spoor.  A typical non-trophy elephant bull that allows for an exciting elephant hunting experience.   Olaf on his elephant bull, the blood from his first shot is visible on the trunk just above the line of the tusks, and blood from the shot into the right ear is also visible. My killing shot is barely discernable, placed slightly above the line between the eyes.  There are always numerous ‘hangers on’ when you hunt council areas, the writer standing at left with a bandana covering his ears due to sweat bees.  In Africa there is no wastage when an elephant is shot  While taking a break during an elephant hunt, Olaf tries burning dry elephant dung to chase away the myriads of sweat bees – it didn’t work! Tracker Lucky Ndlovu watches proceedings from Olaf’s right. Kevin Thomas Safaris Zimbabwe - Eastern Cape E-mail: ktsenquiries@mweb.co.za Website: www.ktsafaris.co.za | ||

|

| One of Us |

I always enjoy your stories. Thanks you, I look forward to more. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Thank you for sharing | |||

|

| One of Us |

Kevin. Thank you once more for an excellent account of one of your hunts. This is as close to real Africa as some of us will ever get. More please.jc | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Hunting

Hunting  African Big Game Hunting

African Big Game Hunting  Lukosi Elephant Encounter - Story by Kevin Thomas

Lukosi Elephant Encounter - Story by Kevin Thomas

Visit our on-line store for AR Memorabilia