The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Hunting

Hunting  African Big Game Hunting

African Big Game Hunting  A Tale of Two Leopards; In the Shadow of the Mountain; The Maneater of the Nyaodza

A Tale of Two Leopards; In the Shadow of the Mountain; The Maneater of the NyaodzaGo  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| One of Us |

A TALE OF TWO LEOPARDS I spend the next few years working in the Zambezi Valley. This valley is a spectacular expanse of ruggedly imposing bush country, bounded by two impressive escarpments and bisected by the mighty Zambezi River itself. The Zambezi Valley is the valley of the buffalo, and of the tsetse fly, and of jesse bush, and much, much more. The Zambezi Valley is, I am to discover, untouched Africa incarnate. Although I am initially reluctant to leave the Lowveld, I soon realize that this awesome valley has much to offer the adventurous soul, and I thoroughly enjoy my time in that place. Few men of the bush are as competent as Mulavu, and none that I have ever come across. And that’s saying something for I have come across many competent men of the bush. Mulavu means lion in the Tonga language and it is a most fitting name for the man in question. Mulavu knows the bush intimately, as does his namesake. I am a mischievous youth at times, constantly craving and looking for stimulation that is not always there, that can never always be there. Most of the time, my efforts at entertaining myself are propelled by an impetuous frame of mind, the plan seldom suitably thought out. Sometimes my efforts backfire horribly, as they did late one night deep in the heart of the Zambezi Escarpment, at a fascinating and totally isolated place known as Mchesu. This mountainous area is named for the Mchesu River, which jinxes and drops away through it, constantly dodging the terrain’s formidable defenders and working its way doggedly toward conclusion, somewhere far in the valley below. It is on the banks of this appealing little mountain river that my boss and I have decided to build a fly camp, primarily for elephant and lion hunting purposes. I arrive at the Mchesu River one day with very little in the way of anything – a Land Cruiser and a few guys, axes and shovels, essential camping gear, food supplies and nothing much else. Whilst trying to find the agreed upon place, I pass through an isolated mission station known as Kariangwe, and manage to employ a couple of local lads there. The word subsequently gets out, and soon I have a gang of about fifteen guys building the camp. It is at these guys that mischief is directed late one night, deep in the heart of the Zambezi Escarpment. My boss is a kindly soul and he understands the loneliness of bush life, he too spends much time away from civilization. Don’t get me wrong, it is a fine way to live, but it can be lonely at times. Because of the loneliness factor the boss has installed a state of the art stereo system in my Land Cruiser, a link to civilization should I ever feel the need for it. I have a dozen or so cassettes and, at times, while away the evenings listening to music. I believe that music has much to offer this world, and I have always derived a great deal of comfort from music sessions. Anyway, amongst my collection of cassettes is a collection of African animal calls, given to me by the kindly boss. The combination of this cassette and my prankster nature is the cause for mischief late that night, on the banks of the Mchesu River. Or maybe I should say the attempted mischief, for the backfire is loud. I have been listening to soft music for some time and am beginning to get drowsy, thinking about bed, when the idea kicks in. It suddenly dawns on me that none of the guys have yet heard the animal call cassette, and that this is a perfect opportunity to entertain myself a little. The guys are camped a couple of hundred metres away and I know that they will all be sound asleep by now. And so I rummage about in the cubbyhole for the animal call tape and insert it in the deck, turning the volume down low and locating the minute long lion recording. Then I twist the volume control to maximum, and the roaring and grunting of alien lions shatters the silent night. There are many lions here in the escarpment, and I confidently assume that the high quality recording will be accepted as nothing other than the real thing. I play snatches of the lion recording on and off for a few minutes, before satisfying myself that the desired effect will have been achieved. Then I walk over to my tent a few metres away, retrieve a feeble torch and my .223 rifle, and head up to where the guys are camped, not far off. Naturally, the silence is absolute at the workers’ camp. I chuckle quietly to myself, thinking what a great prank it is turning out to be. Then I call out into the night. “Varume, pane shumba pa chikowa.†“Men, there are lions down at the river. Come and help me, I wish to scare them off.†I chuckle again, having great fun. It is well known about camp that I have next to no big game hunting experience, and now that fact must be absolutely compounded. I mean, whoever heard of scaring lions off? It is also well known that I have only a light calibre weapon in camp, good for impala and nothing much else. The guys, whom I know are wide awake, must think I am either drunk or have gone totally insane. “Varume,†I persist, “wuya mu batsira.†“Men, come and help.†Silence prevails. A couple of minutes of unanswered false pleading ensues, as I sink the hook as deeply as possible, before deciding to let the guys in on the joke. Although, I never actually get a chance to share the joke, for at that moment I am turned conclusively into the joke. I hear a hut door scraping open and a stocky, bare-chested figure approaches, materializing from the gloom. A soft spoken but strong voice speaks. “You wish to scare away the lions? I shall come with you, let us go.†The man moves off, watched in the feeble torchlight by a thoroughly deflated and disbelieving prankster. “Wait,†I say, and the stocky man turns to face me questioningly. “Let us go and scare the lions,†he says, hovering. I hope that my discomfort is not detected but sense that it is, as I haltingly stammer out an excuse. “They have been silent a while now, maybe they have moved off?†“It may be so. Still, do you wish us to go and check?†“It could be pointless,†I stammer, back-peddling furiously. “It seems they have moved on.†“Yes. Then let us sleep, there is much work to do tomorrow.†With that the stocky man walks back to his hut and the door scrapes shut. Alone in the night I feel humbled. The next day, whilst lashing together the skeleton that shall soon be the dining room with the guys, I get to know something of the stocky man. His name is Mulavu and he has lived in this area forever, as his father did before him. And he is a hunter, as was his father. Mulavu explains that, though he believes himself to be a hunter, unlike his father he is considered by the law to be a poacher. He says he does not wish to break the law and has had to think up alternative means of making a living now. Anyway says Mulavu resignedly, whilst we work a heavy mopani corner pole into position, such is the way of the world, the disappointment that is commonly referred to as changing times and progression. That a man may not hunt to sustain his family in his own homeland, but commercial poaching may continue unabated and on an unprecedented scale – abetted, in all probability, by the very powers that publicly denounce it. Mulavu’s bottom line opinion is that we are not progressing but are stuck firmly in reverse, and I take to the man wholeheartedly. Later in the day, whilst walking down to the river together, I bring up the lions, saying how brave I found his reaction of the previous night to be. Mulavu chuckles and gives me a wink. “Last night was very strange,†he says, “very strange indeed. At first I was uncertain, but not for long. I have lived in this area my entire life and I have heard and seen many, many lions, but never have I heard lions such as those. Those lions were on a kill during the day and not drinking down at the river by night. It was all very strange indeed. The lions intimidated most of the men, but not I. How is it possible, after all, to fear something that is not? And those lions certainly never were, for I have never come across lions that do not leave their prints on the ground.†Smiling wryly to myself, I follow Mulavu down to the river. A truck arrives one day from our main camp Sengwa. Sengwa is a camp we built a few months before, about eighty kilometres away, down in the valley proper, on Lake Kariba’s shoreline. The truck is carrying a couple of buffalo carcasses and instructions from my boss to do some lion baiting and assess cats on the ground, in preparation for a big incoming safari. Mulavu and I set about the task with gusto and we soon have four baits spread about the vicinity, strung up in likely looking spots. We check these baits on a daily basis, anticipating a prompt hit. Although the lions keep a low profile, we soon have several leopards feeding. One day, we find that a pair of leopards is feeding from one of the half-buffalo hunks, in an ebony tree not far from the Mchesu River, downstream from camp. Obviously the leopards in question are male and female, and Mulavu says that they are mating, that it is the right time of the year for that activity. We continue monitoring cats on the ground in the fascinating Mchesu area. The two leopards return to the bait every night, and soon even the considerable half-buffalo is beginning to show the effects of their nightly feasts. When they get the opportunity, leopards, particularly males, are able to eat a disproportionately great deal of meat in a sitting. It is winter and the weather is cool enough now to keep meat for some time. Well, for longer than usual anyway – usual being hot conditions and a couple of days at most. At this time, we can easily get a week’s mileage from bait. One night, a lone male lion that transpires to be moving through the area depletes the bait further, and Mulavu and I become somewhat elated about our ability as lion baiters. The leopards obviously stay away that night, but the lion doesn’t return and they are back on bait the following night. In any case, it turns out not to matter that we fail to get lions feeding, because the client cancels his safari a few days later, due to illness. Mulavu and I consequently do the bait run, dropping all the ripening lion baits for the scavengers. All but the bait in the ebony tree, the two leopards are still feeding and we are both thoroughly enjoying that. Of course, the leopard larder is also ripening, and we realize that we will have to replenish it soon or they will stop feeding. I am allowed to occasionally shoot a couple of impala for workers’ rations, and Mulavu and I decide that, in the interests of furthering our knowledge of leopard behaviour, it would be permissible to sideline some of this ration. Not that we are going to explain ourselves to anyone anyway. No one shall ever know what we get up to in these mountains. We could have a huge poaching racket going on up here if we felt the need – the need that others do feel. Anyway, Mulavu and I go out one day and shoot an impala ram, which we replace the bones and maggot infested, rotting flesh of the buffalo with, stringing it up high in the ebony tree. The leopards are most pleased with the advent of the impala and, though they must already have seriously sagging bellies, gorge enthusiastically on the fresh offering. Early one morning, Mulavu and I surprise the leopards on the bait. I am driving a petrol-propelled Land Cruiser and it has a fairly quiet approach. Not that the leopards are too concerned anyway. Mulavu sees the female first, flattened out on a tree limb, close to the dangling impala carcasse. He gestures and I brake reflexively. As the female descends the tree in a flash, the male appears not forty yards ahead, padding heavy-bellied across the track and giving us an angry glare. The grass is sparse here and, after rolling forward a few more metres, we are treated to a spectacular sighting of the leopards trotting off toward the trees, in no real hurry it seems. The male disappears into cover but the female stops once in the open ground. Curiously she turns back, staring at us for long seconds. Then she too disappears, obviously satisfying curiosity. Leopards are seldom seen in the bush and the sighting excites Mulavu and I tremendously. And it was such a grand sighting, not the normal bush-obscured, fleeting glimpse. Mulavu says that these leopards encounter very little disturbance up here in the mountains, and do not readily fear man yet. We follow the leopard tracks into the trees and a short distance further, just for doing it. And then we amble happily back towards the vehicle – ambling happily along and chatting about leopards. “Let us wait for these leopards tonight,†says Mulavu, “and watch them feed.†Of course, there is no question and we start planning. Shortly afterwards, we complete piecing together a rudimentary blind from sticks, leaves and grass. We situate the blind about sixty yards away from the bait, in a small clump of bush across the track, downwind and well camouflaged. As we drive back to camp, Mulavu and I eagerly anticipate the forthcoming evening. At about 4 pm we leave the Cruiser a fair distance from the bait and walk into our blind. Soon we are firmly ensconced and well concealed within the clump of bush, seated side by side, breathlessly expectant. A short time passes and then we hear the male leopard grunting close at hand, from somewhere downstream. Not fifteen minutes later he is in the tree, appearing on the dinner supporting limb in illusionary fashion, as only leopards can. Without delay, the large tom hooks honed claws into the impala carcass, effortlessly lifting the meat up onto the limb and displaying his remarkable strength. Tom does not waste any time getting stuck in, obviously not going with the ‘ladies first’ theory. And then the lady is also there, sitting at the base of the tree, occasionally inspecting her nails and looking about the place. The leopards are wholly unperturbed and I know that our blind is serving its purpose well. We watch the leopards feeding for about one mesmerizing hour, until the sun sets and darkness descends. And then we listen to them feeding, for several hours more. It is late when Mulavu touches my thigh and leads the way cautiously from the blind, into the bush away from the leopards, leaving them completely undisturbed, as we had wished to. We return a number of times to the blind and watch the leopards feeding. They soon work their way through one impala and we string up another, and then another. It is a most inspiring feeling to watch these remarkable cats feeding in this remote wilderness area, with Mulavu sitting by my side. This is as wild as it gets, I think to myself. Mulavu and I observe much intriguing leopard behaviour from our concealed observatory within that clump of bush, including an evening when mating takes precedence over feeding. Most intriguing behaviour indeed, especially for a virgin like me. We keep the leopards feeding for weeks on end and spend much time watching them from our blind. By now there is a well-worn and most familiar path leading from the blind into the bush. Excursions to view the leopards become a very important part of our routine, an activity that we keenly look forward to. Mulavu even christens the two splendid cats, with very suitable names. They are Induna (Chief) and Musikana (Girl). As the weeks pass, Mulavu and I become very attached to the Chief and his girl. We arrive early one morning to see how much the leopards have fed during the night, and to assess the condition of the bait. We did not sit the previous evening, being totally exhausted by a hard day’s work and turning in very early as a result. Leaving the Cruiser a distance down the road, we walk into the bait. Looking up at the dangling remnants of what was once an impala ram, Mulavu says that the leopards have not fed. We find this to be odd, for they have not skipped a night yet. Even when apparently not hungry, they have always come in and taken a few mouthfuls, making an appearance and guarding their larder from other cats, one assumes. Mulavu suggests that we scout around a little and look for spoor. He says the leopards may have come in and not fed, that he finds their absence to be strange. For what self-respecting Zambezi Valley leopard would turn its nose up at a guaranteed and undisturbed feed? Obviously none that Mulavu has ever come across. We cross the open ground together, walking slowly along and scouring the ground for fresh tracks. Just before the trees, Mulavu discovers what he assures me are the tom’s tracks, from the night before. Mulavu is a master tracker and if he says so then it must be. Mulavu leads the way off, following the spoor and muttering about how unusual it all is – that the tom had definitely come in during the night but had not approached even close to the bait. Mulavu follows the spoor into the tree-line, with me following behind and wondering. Shortly afterwards we find Musikana, the girl. She is lying on her side in the grass, dead and stiffening. The wire snare around her hips has dug in deep and, aided by her own threshing claws, disemboweled her completely. Shocked to the core, I kneel down and stroke her soft velvety coat. After a few minutes of disbelief, we scout about some more and discover a path worn into the earth around the death scene. A path imprinted plainly into the earth by a helpless and confused Chief, throughout the long night, on a repetitive circuit of pain and frustration. With a heavy heart and a massive lump in my throat, I carry the stiffening body of the beautiful girl to the roadside. It is possible that the Chief only moved off when Mulavu and I arrived at the bait early that morning. Certainly he spent many hours with his girl that night, as she died and afterwards. Later in the day I returned to the place with a small gang of guys and we lifted many snares that were obviously meant for antelope. Although we may have saved some, it was too late for at least one beautiful girl. [URL=  ][IMG] ][IMG]IN THE SHADOW OF THE MOUNTAIN Many, many years ago, when the valley was still young and inhabited only by wild animals and Vadoma, there lived a young man who went by the name Mavura. Mavura was born into an influential and powerful Vadoma family, his father a respected elder, held in high esteem by all and accountable only to the Chief himself. Mavura soon grew to be a popular figure – a natural leader, brave warrior and extremely skilled hunter. In time, Mavura proposed to and married the Chief’s favourite daughter, simultaneously elevating his own rank and further cementing his family’s standing in the community. Yes, Mavura certainly became a man of means in the land of the Vadoma. Mavura was a hunter and a highly proficient one. Where others failed, Mavura delivered. He knew the bush better than any living man and was intimately acquainted with the habits of the animals he hunted. When Mavura hunted, success was almost guaranteed, meat and honey plentiful. Mavura hunted throughout the great valley – from the mighty river in the north, across the vastness of the valley itself, up into the rugged escarpment. Always, contrary to the norm, he hunted alone. At times Mavura would be gone for weeks, searching for new hunting grounds. In most African culture, diviner consultation is of paramount importance, particularly when pertaining to really important issues, specifically food supply and consequently tribal survival – the Vadoma are no exception. One day, Mavura approached – as he usually would – the village mudzimu, in order to obtain his spiritual blessing before setting out on a hunt. Now it is said that Mavura, lad about town so to speak, was something of a spiritual sceptic. Much as the modern day western gang-leader would scorn conformity and the church, Mavura would often disregard the wise words of the elders and, more importantly, those of the all-powerful mudzimu. Although the young men and boys of the tribe idolized Mavura for his outspokenness and prowess as a fighter and hunter, most of the elders considered him somewhat arrogant and hotheaded. As is normal in any society, the presence and objective opinion of certain levelheaded mediators usually managed to maintain some semblance of balance – compromise between experience and exuberance if you will. At that time, the mudzimu was a man known as Debvujena (Greybeard) and he was fittingly named. No living man had ever seen a beard such as Debvujena’s. Long and grey, it would, even if meticulously braided, reach the ground when the old man squatted on a low stool holding counsel. It was widely rumored that the longer and greyer Debvujena’s beard became, the more powerful a mudzimu he became. If this was truly the case, then he must indeed be a mighty man. It was whilst seated on his stool of counsel, addressing a small group of young hunters, that Debvujena finally lost patience with the impertinence of Mavura. Attempting to leap to his feet in anger, the old man erroneously stepped on the extremity of his impressive beard and, howling and hopping around in pain, tipped himself head over heels, backwards over the stool. Floundering and cursing in the dust, the respected medium eventually regained his feet, though any degree of composure continued to elude him. Although there were a few stifled giggles, no person dared to laugh out loud. Pointing a gnarled, menacing finger accusingly at a smirking Mavura, Debvujena, for the first time that anyone could remember, totally lost control. Spitting wrath, the spiritual leader loudly and publicly condemned the arrogance of the over confident Mavura and, in a loud voice that the entire village heard, challenged the famed hunter to, ‘Hunt where you like, when you like, and reap the consequences!’ With that, Mavura calmly stood, retrieving his hunting spear from the ground at his side and, without a backward glance, totally scorning tradition, strode purposefully away from the village and into the wild Zambezi Valley. Now it was well known that Mavura’s favourite hunting haunts were in the area surrounding and, indeed, on the very slopes of Chiramba Kadoma* itself. In fact, in those days, Chiramba Kadoma, Mashambanzou and the game rich Mkanga Valley** were some of every Vadoma hunter’s preferred hunting grounds. The mountains and the valley complemented each other well, the former for honey and the latter for meat. It soon spread throughout the small community that Debvujena’s outburst had been Chiramba Kadoma orientated, and that the entire counsel with the hunters had in fact revolved around talk of that place. It transpired that the medium had advised the hunters not to hunt that lunar period in the vicinity of Chiramba Kadoma, that the spirits had warned against it. Predictably, the over-zealous Mavura had argued the issue and ultimately pushed Debvujena into erupting. It was assumed by most people that the impetuous Mavura would make straight for his favourite hunting area, defying everything the aged diviner and the spirits stood for. In the aftermath of Mavura’s disrespectful departure, the talk around the evenings fire glow revolved around that man’s whereabouts, about whether or not he had chosen to directly challenge the spirits. Whenever the popular opinion was voiced, several greybeards were seen, in the humble firelight, to be shaking their heads in sorrow. * Obviously not called Chiramba Kadoma back then. Though I have researched diligently I am not able to trace the pre Chiramba Kadoma name of this mountain. After all, that name only existed many, many years ago, when the valley was still young and inhabited only by wild animals and Vadoma. ** The original home-place of Vadoma. Of course, Mavura never returned. To this day theories and assumptions are bandied about, but no-one knows for certain what became of the man. One common belief, which each and every tribe member has always agreed upon, is that Mavura returned to the mountain. In time, a famed council attended by all the tribal elders was called. The assemblage was presided over by Mavura’s own father-in-law, the Chief, and Debvujena, the all-powerful spirit medium. It was agreed upon by all and sundry at that historical council that, according to the wishes of the spirits, no person would ever again operate, for any reason, within the parameters of Chiramba Kadoma Mountain. And so the legend was born. In the year 1968, a large group of approximately one hundred heavily armed Zimbabwean freedom fighters (Rhodesian guerrilla insurgents) crossed the Zambezi River into what was then Rhodesia. Their goal was to destabilize the country through proactive means – essentially Communist orientated terror warfare – and in so doing, force the steel hand of Ian Smith and his Rhodesia Front Party into bringing about majority rule in Rhodesia. The fighters crossed the Zambezi in dugout canoes under cover of darkness, at a narrow place known as Mupata Gorge. Once in Rhodesian territory, they split up into smaller groups of between twenty and thirty men and set off to various prearranged base camps. One of the groups had instructions to base up in an area close to Chiramba Kadoma Mountain. Amongst this group’s number was a man who was familiar with Chiramba Kadoma and the many mysterious legends associated with that place. This man proposed basing up on the actual mountain itself, the logic being that they would never be discovered in an area where nobody dared go. There was opposition to the proposal as some feared offending the spirits. The spirits hold much sway in Africa, even over hardened young soldiers such as those particular men. Eventually the fighters agreed to establish a semi-permanent camp on the mountain, rationalizing that the spirits were those of black people and not of the Rhodesian Government. It was generally agreed that the spirits would practice leniency, seeing the situation for what it was – the collective cause and will of the people, the struggle for freedom. The fighters set off, marching through the moonlit night toward the imposing flat-topped mountain in the south. In the early morning they reached, and subsequently ascended, Chiramba Kadoma Mountain. They were the first people to do so in a very long time. Unfortunately for those men, nobody had primed the wrathful spirits of Chiramba Kadoma. At the same time, down in the Mkanga Valley, two National Parks rangers were nearing the end of a routine two-week patrol. Before returning to Mkanga Parks Post, the rangers had planned to spend a couple of days scouting about in the vicinity of Chiramba Kadoma, looking for poachers and evaluating wildlife populations in the area. Both men were reasonably familiar with Chewore and local legend and they harboured no intentions of approaching the mountain too closely. It was not long before the rangers discovered the ineffectually disguised spoor of the insurgents. At that turbulent time in history, the country was on full security alert and the Parks men had no difficulty determining that the spoor was that of a large group of guerrillas. Cautiously, with the threat of confronting the fighters not foremost in their minds, the two men tracked the guerrilla gang to a place not far from the legendary mountain. Then, after correctly deducing that the gang was holed up on the mountain, the rangers retreated to a safe position and radioed in a report to Mkanga, summarizing the situation on the ground. Mere hours later, the Rhodesian Airforce unleashed a massive attack on Chiramba Kadoma, bombing it throughout the day. The attack was conclusive, with most of the gang being wiped out by the barrage. Few of the fighters escaped from the mountain and those that did were harangued all the way back to the Zambezi by the army. Amongst the locals, it is said that those who dared defy the spirits of the mountain perished on that day. Evidently the fight for freedom was not cause enough to appease the vengeful, uncompromising spirits of Chiramba Kadoma. The year is 1988 and professional hunter Roger Whittall is hunting buffalo with his son Guy, aged sixteen, in the Mkanga Valley. Under the experienced guidance of his father, Guy is hoping to hunt and shoot a buffalo bull. Accompanying the father and son team are young professional hunter Joe Wright, and Magara, Roger’s trusted and competent tracker. The hunters spend several days tracking and approaching buffalo, giving Guy valuable exposure to buffalo hunting. There is no urgency for there is time at their disposal and the hunters intend drawing out the hunt for as long as they possibly can. All and sundry are enjoying themselves thoroughly, down there in the Mkanga Valley. The hunting party comes up on countless buffalo for they are plentiful in this area. One day, after spending the early morning tracking a small group of dagga boys in a northwesterly direction amongst the foothills of the Mashambanzou Range, the hunters find themselves to be in close proximity to Chiramba Kadoma Mountain. For a short distance further they follow the buffalo tracks, ever closer toward the controversial mountain. Soon they are very close, in the very shadow of the mountain looming menacingly above. Magara suddenly stops, stating that he will go no further, that they are entering a forbidden area. He is emphatic and no amount of logical (Christian influenced) reasoning will change his mind. He says that any person who dares to go further does so against his advice, and at his own peril. Arranging to await the hunters’ return at an agreed upon point further back on the trail, far from the mountain, Magara, with a relieved Parks game scout in tow, hurriedly makes off. The hunters confer briefly, discussing the option of turning back. Even with the dire warnings of Magara still ringing loudly in their ears, they decide to press on. The dagga boy tracks indicate large bulls and, unlike Magara and the game scout, their passion for buffalo hunting far exceeds their fear of the spirits. In any case, civilized men cannot allow superstition and witchcraft to dictate their actions, can they? The white men soon reach the base of Chiramba Kadoma and find that the buffalo have changed tack, opting to skirt the mountain as opposed to ascending it. Chiramba Kadoma is a steep mountain, a daunting challenge for even three tough, battle-hardened dagga boys. In due course the men come up on the buffalo, resting in a small thicket set in close to the mountain’s base. Undetected, the hunters judge the bulls in leisurely fashion, before deciding that none of them quite make the standard. They retreat without disturbing the buffalo, retracing their steps back to the meeting place with Magara. Later, after having abandoned hunting for the day, the hunters slowly wend their way in single file through the foothills, back to where they have left the vehicle. Magara and Roger are leading, followed by Joe, with young Guy and the game scout bringing up the rear. They are a weary bunch for they have hunted hard and the level of awareness is low. The trail they walk is hemmed in on either side by dense undergrowth and visibility is severely restricted. Without warning, all hell breaks loose. Guy sees the buffalo first. It is standing hidden in thick bush not ten metres away, off to the right of the trail. Guy screams out a warning to his father and the buffalo simultaneously breaks cover. Head held high, the bull comes crashing through the scrub, directly at Roger and Magara. This buffalo has several things on its mind, all ultimately equating to violent death – to gore and toss, to trample, pound, crush and maim. Facing down a charge causes adrenalin to pump strongly through one’s veins. This increases reaction speed dramatically whilst outwardly slowing down the actual event. Roger Whittall spins around to face the buffalo, rifle butt instinctively finding his shoulder. In slow motion the bull comes purposefully on – immense bulk propelled by sheer fury, gouging hooves tearing the earth up in its frenzy to obliterate. Mere yards separate attacker and attacked, and the bull’s massive, boss-fronted cranium is completely lowered now, preparing for the toss. The shot, when it finally comes, is again instinctive and taken at the last possible instant. Instinct and adrenalin are a fine combination when working cohesively as they should, and Roger Whittall attests to the fact that, on that particular day, it was those two God given attributes that saved at least one life, possibly more. “In a situation like that you do not think,†he says, “you simply act. It’s a case of do or die, with no go-betweens.†Fortunately for everyone concerned, Roger’s bullet hits the buffalo where base of skull joins spine – a killing shot in any situation. Instantly paralysed, felled and stone dead, the bull drops on top of where Roger Whittall had, seconds before, been standing. Insurance shots from both Magara and Roger serve as just that – pure insurance. After the excitement the men are quiet for a long time, reflecting on what could have happened, had the odds been against. After a while, Roger approaches Magara and initiates conversation. “Nyati achu ya svika pa dusi.†“That buffalo got close,†he says. From his position crouching in the dust Magara looks up. For long drawn out minutes he regards his long-time hunting partner thoughtfully. “Chokwadi,†“That is the truth,†says Magara, “ya svika pa dusi chaizo.†“It got close indeed, too close.†What Magara says next is not what anyone wishes to hear. “I told you not to go to the mountain.†The silence following this statement is oppressive. The minutes slowly tick by before Magara continues. “I told you not to go to the mountain and you chose to ignore my warning. That buffalo,†he indicates the fallen carcass, “was a dire warning from the spirits who, through their powers, momentarily closed our eyes and almost left us to walk right onto the angry bull. The spirits have been merciful for they granted us our sight at the last instant. It is truly fortunate that you kept close to ground level and did not attempt to climb higher, into the mountain itself. Had you been that arrogant, this incident would have been something far more conclusive than a mere caution. Then our eyes would have been shut permanently. We have been fortunate indeed.†With that, Magara stands and shoulders his rifle. “It is getting late,†he says, “let us be off.†Magara walks off down the dusty footpath, leaving a contemplative group of hunters watching his departing form. Roger Whittall can only think how surprising it is that Magara knew they had stuck to the base of the mountain. The hunters had been gone a long time and, after meeting up again with Magara, communication had been decidedly lacking. They had all been, for different reasons that only men understand, somewhat irritated by one another. The fact is, nobody told Magara anything about the earlier excursion into the vicinity of Chiramba Kadoma. And yet he knew. The light is rapidly fading and the hunters are making haste, hoping to reach the vehicle before total darkness descends. Magara, who is leading as usual, suddenly jumps to the side, startled. Everyone is very edgy now and more than one man readies himself for action. It turns out to be a false alarm, only a little rabbit that Magara has almost trodden on. As the group makes off again, Magara is overheard muttering under his breath, muttering something about spirits. About spirits and faulty eyesight. [URL=  ][IMG] ][IMG]THE MANEATER OF THE NYAODZA Crocodile stories are legion in Africa and this is just another. Crocodiles are impressive in that, not only are they one of the longest surviving creatures on earth, but are also the ultimate killing machines. In its own environment, nothing can compare to the combination of this reptile’s speed and power, and that is obviously the reason for its survival. As well as being most impressive creatures, crocodiles also instil great terror in people. The thought of being killed by a crocodile has always been my greatest fear, a greater fear than dying by either fire or mamba bite. That is the extent of the dread these creatures are capable of instilling. Many other Africans feel the same way as I, and crocodiles are accorded huge respect and significant spiritual status amongst rural African communities. I treat crocodiles with far more than respect; I just don’t go there any longer. ‘There’ being close to any water where a croc may possibly be lurking. Very difficult for an ardent fisherman! Aged only twenty-eight, my brother Jonathan is already a competent big game hunter with over ten years experience. Jonny freelances and much of his time is spent hunting the spectacular Zambezi Valley, contracted to various hunting operators. Although I shall surely be accused of bias, the fact is that Jonny is an extremely skilled hunter, his services in demand. Because of this, he hunts for much of the year with little downtime. Jonny is most satisfied with the arrangement and actually becomes difficult to live with when not ‘out there’ in active pursuit. Hunting is in the genes of man but is more so in the jeans of Jonny. When forced to take a few days off, Jonny and his loyal trackers (Amos and Clever) come home with many tales of action and adventure from the bush, regaling us all with exciting stories from their most recent excursions into Africa’s remote hunting grounds. Until they get itchy feet and head off once more that is. One such story, which made quite an impression on me, is the one that follows. “That hunt was an extreme challenge from the word go,†says Jonny. “A Zambezi Valley elephant hunt in December of a good rainy season, well you can imagine what it was like. I had never before, and have never since, operated terrain like that. The bush was so dense it made everything I had so far hunted look like a walk in the park. The roads were quagmires and we spent a lot of time stuck and winching ourselves out. I warned my client Dennis Frings of all this beforehand, when he booked the hunt. Being a seriously committed elephant hunter he went ahead and booked anyway. That was the great thing about hunting with Dennis – he was a serious hunter. He was looking for a good bull, sixty pounds or more, and he wouldn’t settle for less. He knew our chances were slim at the year’s end, or any time for that matter, and yet he was prepared to take the gamble. Dennis is one of those guys that live for the hunt. “We tracked, approached and judged many, many elephant on that safari – unfortunately nothing made the grade. On reflection I reckon we looked at well over fifty bulls without seeing anything suitable. As I have already said, the going was tough. Obviously most of our time was spent on spoor, walking unbelievably prohibitive terrain. Working those elephant paths through that saturated, dripping jesse was daunting, time consuming toil, to say the very least. We had our objective however, and we stuck to our guns. On one occasion we came up on a bull carrying about sixty pounds. Frustratingly, he was only carrying one side, the other tusk broken off close to the lip. We re-intensified our efforts. “Everybody has a mamba story or two to tell, but how often do we actually come across these snakes in the bush? Not often and that’s the truth. Twenty-eight years of living in mamba populated areas and I’ve probably seen about fifty mambas, that’s also the truth. Two sighted for every year of my life, maybe. And yet, on that hunt alone we came across two, and let me assure you we came across them! Up close and personal! On both occasions they attacked without warning and I have never witnessed this before. As you know, although these snakes have a reputation second to none, mamba attacks are rare. They, like any other wild animal, prefer to be left alone and in peace. Those two mambas did not prefer to be left alone however, and they came actively seeking conflict. Now I know that many mamba stories are exaggerated, to an extent at least, and I don’t want to do that here. I shall try to tell it as it happened. But bear in mind that the happenings on that hunt did have a huge effect on me, and on everyone else present. Yes, that hunt was truly extraordinary. “The first incident occurred whilst we were driving a really primitive hunting track through some broken country close to the escarpment. I was negotiating the Cruiser down a steep incline into a narrow bush choked gully, Dennis in the passenger seat beside me, when excited cries from the rear caused me to brake sharply. Braking was a mistake that was fortunately negated by circumstance. The wheels locked but only managed to gain purchase briefly on the slippery incline. During the moment we were stationary, a mamba struck at and connected the vehicle twice, though I never actually saw the first strike. As the cries from the rear grew louder, I turned in the seat, facing out the window. Before seeing the snake, I loudly enquired ‘Chi cho?’ ‘What is it?’ And then, as the vehicle lost its grip and began sliding, I saw the mamba from the corner of my eye. Raising itself from the long grass on the road verge slightly behind the cab, and attaining an incredible height above ground level, the snake was in the process of implementing the second strike. I was dumbstruck and my foot remained firmly depressed on the brake. The entire enactment took place in a millisecond in any case, and the mamba hit the vehicle for the second time. We slid down into the chikowa, and thankfully the third strike (if there was one) never connected. I opted not to hang about the vicinity and powered the Cruiser up the opposite bank, further on down the road, away from the scene. Fortunately, the tires performed their function this time. “Amos, Clever and the National Parks scout were all badly shaken by the incident. Amos in particular was a bit of a wreck, having come closest to receiving an injection of mamba venom. Everyone knows what happens after this. As I said, the mamba struck twice, both times fortunately connecting with metal. The guys told me that the first strike hit the roll-bar, mere centimetres from where Amos was sitting on the hunting seat. The second strike made contact with the bin, near the tailgate. We all took time to cool off and chat a bit before continuing on our way. Little did anyone realize then, but that incident would not be close to the most impressionable event provided by that hunt. A lot more was to come. “A few days later we were following promising elephant spoor along a narrow, hemmed in elephant path, through some thick jesse not far from the Nyaodza River. It was there that the second mamba incident took place. Clever had just dropped back in the line to tie a bootlace, and was bringing up the rear, when the mamba struck. After reconstructing events later, it was thought that the mamba, which was entwined in overhanging branches under which we passed, struck at the game scout and missed. It subsequently overbalanced, slipped from its limb, and landed squarely across the unfortunate shoulders of Clever. Can you believe that! Sensing commotion behind, I turned in time to see Clever flick the snake instinctively from him, and bolt like an Olympic sprinter into the supposedly impregnable jesse. Again, it all happened in a flash and it was remarkable that nobody received a bite. The snake actually struck at and missed Clever at least once – a miracle really. That mamba was huge and, as it made off through the long grass, shimmering fronds betrayed its progress. There were men bolting in all directions and obviously I didn’t try and shoot it. What are you going to do with a heavy calibre rifle anyway? And of course there was no time. That snake was there and then it was gone, in a blur of mind-boggling speed. I saw that mamba more clearly than the previous one and I don’t believe I have ever seen any bigger. Granted, the situation heightened senses dramatically, but nonetheless the size of that snake was phenomenal. “If the first mamba attack got the trackers a little shaken, the second very nearly pushed them over the edge. In most African culture there is reason for every occurrence, and the second mamba was more than enough of both occurrence and reason for Amos, Clever and the game scout. The rest of the day was spent in silence as everyone thought about it, or tried not to think about it. That evening back at camp, Amos came to my sleeping tent. “Boss, handisi ku fara.†“Boss, I am not happy,†he said. I decided against telling him that he should be happy he was still alive, and instead asked what could possibly be bothering him. “Ma rowambira* achu, ne imwe nyaya. Pane mushonga pano.†“These black mambas and other things, there is bad medicine in this place.†*Rovambira literally means ‘striker of rock-rabbits’, the rock rabbit (dassie) being favourite prey of the mamba. I agreed that the mambas had indeed been frightening, but said that incidents like it do happen and that it meant nothing, certainly not that there was bad mushonga involved. I then asked what else was bothering him. Amos explained that stories regarding several strange disappearances had reached camp from a nearby fishing village, and that all the camp staff were understandably concerned. Now, as you well know, Africans, particularly Zambezi Valley dwellers, are extremely superstitious. Someone does not simply get eaten by a lion or bitten by a snake or die prematurely from illness. There is always an involved explanation for such a happening; always it is spiritually orientated. Most often the deceased, or someone close to that person, has seriously offended the spirits in some way. The majority of unnatural deaths that occur in the majority of rural Africa are rationalized in this fashion – it is the retribution of the all-powerful spirit world. The same is true of individuals or families that have been blessed with good fortune, they are said to have pleased the spirits. “Anyhow, the talk about the woods was that several men had mysteriously vanished and that evil was most certainly at play. It was said that everyone should tread very carefully when going about their business. The disappearances, added to the unnatural behaviour of the two mambas, were almost too much happening for Amos. He said that the mamba attacks were warnings that should not be ignored, and that he didn’t feel we should be hunting the valley at this time of the year. He said that we had never hunted the Zambezi in December before, and that hunting this late in the season was, like the attacking mambas, unnatural. Amos even went to the extent of saying that he felt we should bring the hunt to a close as soon as possible. Amos lives for the hunt and this comment was most uncharacteristic. Never before or since has he said anything like that, and the power of his conviction actually shook me up a little. Events were certainly having a profound effect on Mr Amos Magungu. Anyway, I finally persuaded him to see what I considered reason and to calm down. There were only a few days left of the hunt and we owed it to our friend Dennis to focus totally on bringing his hunt to a successful conclusion, or to sweat great quantities in the attempt. I asked Amos how long we had worked together and whether he thought I would allow any harm to come to any member of the team. He replied that a wounded and charging lion was one thing, but a wounded and charging lion propelled by the spirits was a completely different ballgame. Nobody has more power than the spirits in Africa. Anyhow, though still muttering and visibly disturbed, Amos left calmer than when he arrived, saying he would meet me early in the morning for hunting, that the sooner we got this elephant out of the way and went home the better. “Over pre-dawn coffee the next morning, I told Dennis about Amos’s visit of the previous night, and of the mysterious disappearances at the nearby village. I warned him that the guys might begin to appear less keen than before, explaining why this may happen. Though Dennis was no stranger to Africa and African ways, I wanted him to be fully briefed before he picked up on any strange behaviour. Dennis had hunted with me several times before and we knew each other pretty well. He said he trusted my judgment and would go along with anything I suggested. I suggested we go elephant hunting. We had less than a week left and needed to cover as much territory as was humanly possible in that time. I finished off my coffee telling Dennis that I did not think the trackers and camp staff would let us down. Amos had assured me this would not happen and I knew his word was good. As you well know, Amos is my best friend and most trusted confidant of many years. Conversel | ||

|

| One of Us |

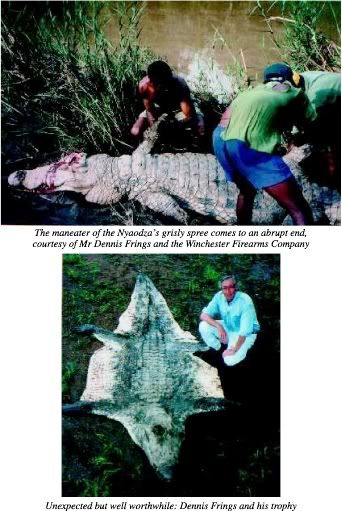

I see 'the maneater' was cut short. Sorry. Here's the whole story and photos [URL=  ][IMG] ][IMG]THE MANEATER OF THE NYAODZA Crocodile stories are legion in Africa and this is just another. Crocodiles are impressive in that, not only are they one of the longest surviving creatures on earth, but are also the ultimate killing machines. In its own environment, nothing can compare to the combination of this reptile’s speed and power, and that is obviously the reason for its survival. As well as being most impressive creatures, crocodiles also instil great terror in people. The thought of being killed by a crocodile has always been my greatest fear, a greater fear than dying by either fire or mamba bite. That is the extent of the dread these creatures are capable of instilling. Many other Africans feel the same way as I, and crocodiles are accorded huge respect and significant spiritual status amongst rural African communities. I treat crocodiles with far more than respect; I just don’t go there any longer. ‘There’ being close to any water where a croc may possibly be lurking. Very difficult for an ardent fisherman! Aged only twenty-eight, my brother Jonathan is already a competent big game hunter with over ten years experience. Jonny freelances and much of his time is spent hunting the spectacular Zambezi Valley, contracted to various hunting operators. Although I shall surely be accused of bias, the fact is that Jonny is an extremely skilled hunter, his services in demand. Because of this, he hunts for much of the year with little downtime. Jonny is most satisfied with the arrangement and actually becomes difficult to live with when not ‘out there’ in active pursuit. Hunting is in the genes of man but is more so in the jeans of Jonny. When forced to take a few days off, Jonny and his loyal trackers (Amos and Clever) come home with many tales of action and adventure from the bush, regaling us all with exciting stories from their most recent excursions into Africa’s remote hunting grounds. Until they get itchy feet and head off once more that is. One such story, which made quite an impression on me, is the one that follows. “That hunt was an extreme challenge from the word go,†says Jonny. “A Zambezi Valley elephant hunt in December of a good rainy season, well you can imagine what it was like. I had never before, and have never since, operated terrain like that. The bush was so dense it made everything I had so far hunted look like a walk in the park. The roads were quagmires and we spent a lot of time stuck and winching ourselves out. I warned my client Dennis Frings of all this beforehand, when he booked the hunt. Being a seriously committed elephant hunter he went ahead and booked anyway. That was the great thing about hunting with Dennis – he was a serious hunter. He was looking for a good bull, sixty pounds or more, and he wouldn’t settle for less. He knew our chances were slim at the year’s end, or any time for that matter, and yet he was prepared to take the gamble. Dennis is one of those guys that live for the hunt. “We tracked, approached and judged many, many elephant on that safari – unfortunately nothing made the grade. On reflection I reckon we looked at well over fifty bulls without seeing anything suitable. As I have already said, the going was tough. Obviously most of our time was spent on spoor, walking unbelievably prohibitive terrain. Working those elephant paths through that saturated, dripping jesse was daunting, time consuming toil, to say the very least. We had our objective however, and we stuck to our guns. On one occasion we came up on a bull carrying about sixty pounds. Frustratingly, he was only carrying one side, the other tusk broken off close to the lip. We re-intensified our efforts. “Everybody has a mamba story or two to tell, but how often do we actually come across these snakes in the bush? Not often and that’s the truth. Twenty-eight years of living in mamba populated areas and I’ve probably seen about fifty mambas, that’s also the truth. Two sighted for every year of my life, maybe. And yet, on that hunt alone we came across two, and let me assure you we came across them! Up close and personal! On both occasions they attacked without warning and I have never witnessed this before. As you know, although these snakes have a reputation second to none, mamba attacks are rare. They, like any other wild animal, prefer to be left alone and in peace. Those two mambas did not prefer to be left alone however, and they came actively seeking conflict. Now I know that many mamba stories are exaggerated, to an extent at least, and I don’t want to do that here. I shall try to tell it as it happened. But bear in mind that the happenings on that hunt did have a huge effect on me, and on everyone else present. Yes, that hunt was truly extraordinary. “The first incident occurred whilst we were driving a really primitive hunting track through some broken country close to the escarpment. I was negotiating the Cruiser down a steep incline into a narrow bush choked gully, Dennis in the passenger seat beside me, when excited cries from the rear caused me to brake sharply. Braking was a mistake that was fortunately negated by circumstance. The wheels locked but only managed to gain purchase briefly on the slippery incline. During the moment we were stationary, a mamba struck at and connected the vehicle twice, though I never actually saw the first strike. As the cries from the rear grew louder, I turned in the seat, facing out the window. Before seeing the snake, I loudly enquired ‘Chi cho?’ ‘What is it?’ And then, as the vehicle lost its grip and began sliding, I saw the mamba from the corner of my eye. Raising itself from the long grass on the road verge slightly behind the cab, and attaining an incredible height above ground level, the snake was in the process of implementing the second strike. I was dumbstruck and my foot remained firmly depressed on the brake. The entire enactment took place in a millisecond in any case, and the mamba hit the vehicle for the second time. We slid down into the chikowa, and thankfully the third strike (if there was one) never connected. I opted not to hang about the vicinity and powered the Cruiser up the opposite bank, further on down the road, away from the scene. Fortunately, the tires performed their function this time. “Amos, Clever and the National Parks scout were all badly shaken by the incident. Amos in particular was a bit of a wreck, having come closest to receiving an injection of mamba venom. Everyone knows what happens after this. As I said, the mamba struck twice, both times fortunately connecting with metal. The guys told me that the first strike hit the roll-bar, mere centimetres from where Amos was sitting on the hunting seat. The second strike made contact with the bin, near the tailgate. We all took time to cool off and chat a bit before continuing on our way. Little did anyone realize then, but that incident would not be close to the most impressionable event provided by that hunt. A lot more was to come. “A few days later we were following promising elephant spoor along a narrow, hemmed in elephant path, through some thick jesse not far from the Nyaodza River. It was there that the second mamba incident took place. Clever had just dropped back in the line to tie a bootlace, and was bringing up the rear, when the mamba struck. After reconstructing events later, it was thought that the mamba, which was entwined in overhanging branches under which we passed, struck at the game scout and missed. It subsequently overbalanced, slipped from its limb, and landed squarely across the unfortunate shoulders of Clever. Can you believe that! Sensing commotion behind, I turned in time to see Clever flick the snake instinctively from him, and bolt like an Olympic sprinter into the supposedly impregnable jesse. Again, it all happened in a flash and it was remarkable that nobody received a bite. The snake actually struck at and missed Clever at least once – a miracle really. That mamba was huge and, as it made off through the long grass, shimmering fronds betrayed its progress. There were men bolting in all directions and obviously I didn’t try and shoot it. What are you going to do with a heavy calibre rifle anyway? And of course there was no time. That snake was there and then it was gone, in a blur of mind-boggling speed. I saw that mamba more clearly than the previous one and I don’t believe I have ever seen any bigger. Granted, the situation heightened senses dramatically, but nonetheless the size of that snake was phenomenal. “If the first mamba attack got the trackers a little shaken, the second very nearly pushed them over the edge. In most African culture there is reason for every occurrence, and the second mamba was more than enough of both occurrence and reason for Amos, Clever and the game scout. The rest of the day was spent in silence as everyone thought about it, or tried not to think about it. That evening back at camp, Amos came to my sleeping tent. “Boss, handisi ku fara.†“Boss, I am not happy,†he said. I decided against telling him that he should be happy he was still alive, and instead asked what could possibly be bothering him. “Ma rowambira* achu, ne imwe nyaya. Pane mushonga pano.†“These black mambas and other things, there is bad medicine in this place.†*Rovambira literally means ‘striker of rock-rabbits’, the rock rabbit (dassie) being favourite prey of the mamba. I agreed that the mambas had indeed been frightening, but said that incidents like it do happen and that it meant nothing, certainly not that there was bad mushonga involved. I then asked what else was bothering him. Amos explained that stories regarding several strange disappearances had reached camp from a nearby fishing village, and that all the camp staff were understandably concerned. Now, as you well know, Africans, particularly Zambezi Valley dwellers, are extremely superstitious. Someone does not simply get eaten by a lion or bitten by a snake or die prematurely from illness. There is always an involved explanation for such a happening; always it is spiritually orientated. Most often the deceased, or someone close to that person, has seriously offended the spirits in some way. The majority of unnatural deaths that occur in the majority of rural Africa are rationalized in this fashion – it is the retribution of the all-powerful spirit world. The same is true of individuals or families that have been blessed with good fortune, they are said to have pleased the spirits. “Anyhow, the talk about the woods was that several men had mysteriously vanished and that evil was most certainly at play. It was said that everyone should tread very carefully when going about their business. The disappearances, added to the unnatural behaviour of the two mambas, were almost too much happening for Amos. He said that the mamba attacks were warnings that should not be ignored, and that he didn’t feel we should be hunting the valley at this time of the year. He said that we had never hunted the Zambezi in December before, and that hunting this late in the season was, like the attacking mambas, unnatural. Amos even went to the extent of saying that he felt we should bring the hunt to a close as soon as possible. Amos lives for the hunt and this comment was most uncharacteristic. Never before or since has he said anything like that, and the power of his conviction actually shook me up a little. Events were certainly having a profound effect on Mr Amos Magungu. Anyway, I finally persuaded him to see what I considered reason and to calm down. There were only a few days left of the hunt and we owed it to our friend Dennis to focus totally on bringing his hunt to a successful conclusion, or to sweat great quantities in the attempt. I asked Amos how long we had worked together and whether he thought I would allow any harm to come to any member of the team. He replied that a wounded and charging lion was one thing, but a wounded and charging lion propelled by the spirits was a completely different ballgame. Nobody has more power than the spirits in Africa. Anyhow, though still muttering and visibly disturbed, Amos left calmer than when he arrived, saying he would meet me early in the morning for hunting, that the sooner we got this elephant out of the way and went home the better. “Over pre-dawn coffee the next morning, I told Dennis about Amos’s visit of the previous night, and of the mysterious disappearances at the nearby village. I warned him that the guys might begin to appear less keen than before, explaining why this may happen. Though Dennis was no stranger to Africa and African ways, I wanted him to be fully briefed before he picked up on any strange behaviour. Dennis had hunted with me several times before and we knew each other pretty well. He said he trusted my judgment and would go along with anything I suggested. I suggested we go elephant hunting. We had less than a week left and needed to cover as much territory as was humanly possible in that time. I finished off my coffee telling Dennis that I did not think the trackers and camp staff would let us down. Amos had assured me this would not happen and I knew his word was good. As you well know, Amos is my best friend and most trusted confidant of many years. Conversely though, I also knew of the powerful influence the spirits have over most Africans – still do. That was what worried me more than anything. “To their credit, none of the guys upset the apple cart. Although it was obvious to me that fear dominated, the men put their heads down and performed commendably. We walked a great distance that last week, following individual bulls and small bachelor groups relentlessly. As was the case before, we came up on many bulls. As was also the case before, nothing made the grade. It was on the third last day, whilst following the tracks of a lone bull along the Nyaodza River, a preferred hunting area of mine, that we saw the crocodile. For reasons that shall become clear, that crocodile completely stole the show, defocusing us wholly from elephant hunting for the remainder of the safari. “We had been following the bull since early morning and by noon it was showing no sign of slowing up. Nearing the end of its journey to Lake Kariba, the Nyaodza River bisects the boundary of Charara Safari Area – where we were hunting – and the Kaburi Wilderness Area, which has National Park status. I knew that we would soon come to this boundary and be forced to turn back. We had been tracking for about five or six hours, negotiating the prohibitive ravine painstakingly, when we reached the boundary and abandoned the chase. Disappointed, we took a break and drank some water. And that was when Amos saw the croc. It was basking on a sandbank across the river on the Parks side, about a hundred yards away. Many crocs populate the Nyaodza and one encounters them regularly along its course. This croc however, was a croc with a difference. When Amos pointed it out, I saw immediately that it was a huge specimen, as large as any I had ever seen. Even its size would not have held our attention for too long though, were it not for the fact that Amos noted something that looked like a vundu (giant catfish) in its massive jaws. After all, we were on an elephant bull hunt and fast running out of hunting time. Added to which, Dennis did not want a croc and the beast was in the National Park even if he had wanted one. I shall forever remember the moment that I lifted my binoculars to get a better look at that crocodile. The binos were not initially focused and I spent a few seconds adjusting, suddenly the croc leapt into focus. I was totally shocked to see that it was not a vundu in the monster’s jaws, but a human leg – feet, toes and all. Hurriedly I dropped the binoculars from my eyes. “It took us a couple of hours to get to the nearest National Parks post and report the man-eater. Predictably, it was difficult to get a decision from the personnel present. I told them that we would willingly shoot the croc, and that I felt we should, before it took someone else. I told the warden and rangers about the disappearing people, and that I believed the croc was responsible for more than one killing. After trying his utmost to confuse himself with bureaucracy, the warden accepted our offer to shoot the problem animal. I may have influenced his decision somewhat when I suggested that, if no action were taken, someone may be held responsible for any further deaths. Given the green light, we drove in rally-like fashion back to the Nyaodza. “Dennis took the crocodile late in the afternoon with a perfectly placed brain shot from about seventy yards. After threshing convulsively on the sand for a while, the dead brain stilled the massive body. It turned out to be a truly awesome specimen, measuring over sixteen feet. After loading the weighty reptile into the Cruiser, and bagging the leg that it had not yet eaten, we made off back to camp. From there I contacted the local police by radio and told them what had transpired. Naturally, they were reluctant to come and retrieve the human parts that were obviously contained within the croc’s belly. After they had exhausted all of their excuses, and circumspectly asked me to carry out the task for them, I ran out of patience. I told them that my job was done with the shooting of the croc and that I was not authorized to do their work for them. Some time afterwards, the grumbling cops arrived at camp and set about their grisly task. Much partially digested human being came from out of that crocodile’s stomach.†It was later determined that as many as five fishermen from several villages may have been killed by that croc over an inexplicable period of two months or so. Obviously Jonathan’s already God like status amongst the locals received an incredible boost from the incident described. Everyone was extremely grateful to know that the disappearances were not spiritually orientated, that a mere flesh and blood crocodile had been responsible all along. After all, had it been an angry spirit disguised as a crocodile, no bullet would have achieved what that hunter’s bullet managed. In Africa, spirits are able to turn bullets to water with very little effort. | |||

|

| One of Us |

David, I really enjoyed reading In the Shadow of the Mountain. My wife and I will be hunting leopard and buff with Magara and Winston with Roger Whittall Safaris June 2 through 17 this year. | |||

|

| One of Us |

HAY-MAN Sir, thanks very much for your kind words, I'm glad you enjoyed the story. Your choice of operator and area for your forthcoming hunt was very wise, and Magara, your PH to be, is one of the very finest PH's in Africa. If you wish, I'll send you some more stories about Chewore and hunting there. Just send me a private message or email me on hulmour@yahoo.com. We look forward to your arrival, you are going to have a great time. Dave | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Hunting

Hunting  African Big Game Hunting

African Big Game Hunting  A Tale of Two Leopards; In the Shadow of the Mountain; The Maneater of the Nyaodza

A Tale of Two Leopards; In the Shadow of the Mountain; The Maneater of the Nyaodza

Visit our on-line store for AR Memorabilia