The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Hunting

Hunting  African Big Game Hunting

African Big Game Hunting  Witchdoctors, Vadomas and Elephant Bulls. Pictures added

Witchdoctors, Vadomas and Elephant Bulls. Pictures addedGo  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| One of Us |

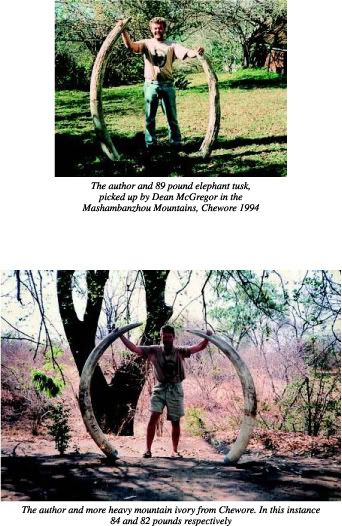

As an afterthought, I have decided to post a story from my book 'The Shangaan Song'. I shall try and post a photo of the tusks, but only have it in adobe reader right now and am having trouble transferring it. Hope you enjoy the read. WITCHDOCTORS, VADOMAS AND ELEPHANT BULLS [URL=  ][IMG] ][IMG]I seldom use the term ‘witchdoctor’.* This word is a first world invention that is misleading and very open to misinterpretation, insinuating sorcery and suchlike. I most often refer to a spirit medium as exactly what he is – a medium or diviner. For the titling of this story, however, I opted to go the controversial route, for pure effect. Somehow I don’t think that ‘Mediums, Vadomas and Elephant bulls’, or ‘Diviners, Vadomas and Elephant bulls’, would have had quite the same impact as the above heading. Anyway, in Shona a medium is a mudzimu or mhondoro, and so we shall use mudzimu for the purpose of this story. One of my jobs in Chewore is to ensure that the local mudzimu is appeased at all times. Appeasement is not actually as difficult as one would imagine, with meat, the universal currency of Africa, never failing to achieve the desired effect. Obviously there is always much meat at my disposal and, consequently, we have a most content local mudzimu, which is just as well. Mediums have huge influence in Africa, particularly in remote rural areas such as the Zambezi Valley. It is in any hunting operator’s best interests to keep the local * ‘Witchdoctor’ is a generalization used to ‘represent’ either a n’anga (traditional healer) or a mudzimu (spirit medium). As I have stated above, it is misleading. mudzimu happy, lest the hunting and associated operations suffer. Should a particular mudzimu wish, he could instantly bring any work in his jurisdiction to a grinding halt. All it takes is for him to dispatch his messenger with a warning. An entire labour force may be rendered totally incapacitated by a visit from the mudzimu’s messenger. In any case, we don’t have to worry too much about this happening at Mana-Angwa, because the gopher team has the local mudzimu feeding happily from their hands – happily and literally. The months pass and I deliver much meat and warm wishes to the local spirit medium, via guys that are permitted an audience. At various times, when the chaps in the know deem it appropriate, particularly before a big incoming hunt, I drive a couple of them off to chat with the mudzimu. The mudzimu who controls this area lives across the Angwa River in Dande Communal Land, at a little village called Masoka, about fifteen kilometres from camp. Whenever mediation visits to the mediator take place, we leave well before dawn, the best time for communication being as the sun rises. And so, bleary eyed with sleep and laden with meat and other gifts, we head off to appease the mudzimu. I always park at the same place on the roadside not far from Masoka Village, and the guys head off into the bush bearing gifts, bound for the mudzimu’s secret place. Obviously, being of a different tribe and all, I am not permitted to accompany the gift bearers. As the first rays of a fiery Zambezi dawn spill into the valley, the messenger blows his kudu horn trumpet mournfully from somewhere deep in the bush. It is a signal to all that the mudzimu is about to begin the day’s work – that he shall soon be in attendance. The divining never takes much longer than an hour, and then the guys return and we drive home. They never tell me much about proceedings but I know a little about it anyway. I should imagine that they have to be in place before sunrise and the messenger’s mournful call. The chances are that they will never see the mudzimu entering the divining hut, but will find him inside when instructed to enter by the messenger. After removing their shoes they probably enter the hut on hands and knees, keeping their lowly heads low, beneath the seated mudzimu’s own head. And then, well Westerners would say the bones are thrown. After a few months working in Chewore and adhering to a strict policy of appeasement, I come to discover the identity of the Masoka mudzimu. Not only do I discover who he is, I actually meet him in person, at his own instigation. As it transpires, a couple of the local Korekore guys that work for us have been speaking about me at Masoka, on their days off. Without trying to appear modest, I relate well to most other people, regardless of ethnicity, including those that work for me in Chewore. It seems that I have received some positive reports at Masoka and, though it may also have something to do with constant meat deliveries, the mudzimu lets it be known that he wishes to meet with me. Stanley, one of our waiters, delivers the message in secret one day. Stanley makes me swear to keep it all quiet, unless the mudzimu says otherwise, when we meet. He says the mudzimu wishes to speak about a number of issues, and that we should meet at a place and time to be decided. Naturally I am most excited, struggling to contain myself as I wait for confirmation. A week or so later, Stanley gives me the nod and reveals all. The meeting is actually called for at a very suitable time, when we are all expectantly awaiting the imminent commencement of a big elephant hunt. And so, one afternoon Stanley guides me to a secret place down on the Angwa River, for my meeting with the mudzimu of Masoka. The mudzimu is a soft-spoken and seemingly considerate man, not at all the fire and brimstone I had expected. He is well heeled and has a good command of English. His name is Vusa Chipembere (Rhinoceros)* and, as well as being the local spirit medium, he is a small-scale Dande farmer, as were his father and his father before him. Like their namesake, the Chipembere clan has been in the Zambezi Valley for a very long time. Unlike their namesake, the clan is not facing total annihilation. We chat for several hours that day – the mudzimu, Stanley and I – and I enjoy the experience enormously. Vusa is an intelligent man and one that I should like to turn to for advice. I believe that the Masoka people are fortunate to have a man like Mr Rhinoceros guiding them. We talk of many things – from hunting to farming, the weather and local history. I have many questions for Vusa, he knows the area intimately and is not averse to sharing his vast knowledge. Vusa Chipembere is very proud of his people and he loves the land in which he lives. I am certainly enriched by the encounter with the mudzimu that day, on the banks of the Angwa River. All too soon it is time to go, and I offer Vusa a lift home. He declines with thanks, saying it is not far to Masoka through the bush and that he enjoys walking. Before parting ways, I tell him that we have a very important client arriving in camp soon, a very important client who shall be hunting for a big elephant bull. The mudzimu bobs his head a couple of times, bringing hand to chin thoughtfully, before speaking. “Tell the hunters to look in the mountains,†he says. “As you know there are many elephants in Chewore and it is not much of a problem to find a mature bull. But the truly large elephant are in the mountains of the elephant – Mashambanzhou (the washing place of elephants). The big bulls spend most of their time in the mountains at this time, away from the cows in the valley below. If one wishes to hunt just any bull, then the valley is the place to hunt, but the heavy ivory is now in the mountains. However, warn the hunters that the mountains are harsh. I think it is a long time since anyone has hunted those mountains. The Mashambanzhou are not kind to men. The only men hardy enough to move about freely in the mountains are the Vadoma, and no other man is as capable as a Vadoma in the bush. There is very little water in the mountains, particularly at this time, and a man would be severely tested there. Yes, the Mashambanzhou are only for the most determined of hunters, but the heavy ivory is there.†With that Vusa bids us farewell, making off into the bush. Although highly unorthodox, I have just experienced an interpretation of sorts, from a genuine mudzimu. I have not yet met the professional hunter who is to conduct the elephant hunt but his reputation as a competent hunter precedes him. I meet him a few days later, when he arrives in camp, the day before his client is due. He turns out to be a likeable chap of whom I enjoy the company. He tells me that he has hunted with the expected client before, and that he is a difficult and strong willed customer who is hell bent on shooting a very good elephant bull. The PH also asks if I have seen any bulls worth mentioning recently. I reply that I haven’t, but go on to tell him what the mudzimu suggested, half-expecting ridicule. But this hunter appears to be an open-minded fellow, well Africa versed. He says that what the mudzimu says is true, that hunting the mountains is the best chance anyone has of finding a big elephant at this time, but that hunting the mountains is no joke. He says the client is a fit man and he will suggest it to him the following day, when he arrives. The client does turn out to be a difficult man, but is made worthy by the fact that he is an awfully keen hunter. He can’t wait to get the show on the road but stresses, over dinner on that first night, the importance of taking only a large bull – nothing under sixty pounds. Sixty pounds in this day and age is an extremely tall order and everyone at the dinner table is well aware of this. The professional hunter then speaks with the client about the mountains, explaining the positive and negative aspects of hunting there. As I have said, this client is a *AKA Nyamasoka, which is more of a title than a name, I guess. keen hunter looking for particularly large ivory. These two hunters shall be the first to tackle the Mashambanzhou Mountains in some time. At times I am fortunate enough to accompany hunters and at other times I am not, it all depends on gopher workload. A hunting apprentice has extremely diverse responsibilities and nothing is ever cut and dried. The good thing about it is that no two days are the same. On this particular hunt, I know from the word go that I shall not be spending too much time with the elephant hunters. I have plenty of other work to do, including the building of a fly camp somewhere in the Mveya Hills, a task that I have repeatedly delayed the commencement of. The hunters leave camp well before dawn the next morning, destination Mashambanzhou. I leave a little while later, destination Mveya somewhere, after a prolonged, kick-starting coffee session has given the hunters dust ample time to settle. Although anyone is usually exhausted by a hard days work in Chewore, nothing could ever compare with the state of those elephant hunters after a day in the mountains. Seldom have I come across fatigue such as this; these men are totally wasted when they arrive at camp in the evenings. Even the trackers begin to show signs of wear and tear, challenged to the limit by the mighty Mashambanzhou. I have never been into these mountains but I begin to glean an understanding of what it must be like, from the hunters’ campfire descriptions. Albeit the fact that the descriptions are brief and to the point, before bed beckons the shattered men away. Each morning well before dawn the hunters leave camp, Mashambanzhou bound. A few days into the safari, my good friend Dean McGregor unexpectedly joins us in camp. Dean is a professional hunter and guide with a constant yearning for remote areas and adventure. An extremely competent bush fundi (guru) with years of experience, he is a good man to have around. Deano’s knowledge of life is vast and he is a fine friend and advisor. It turns out that he has a couple of weeks break from guiding in the Kariba area, and that he decided to spend some of this time in Chewore with us, hoping to involve himself in some form of adventure no doubt. Anyway, I am glad that my buddy Dean is to spend time with us. Predictably it does not take Dean long to hook himself up with, and become completely absorbed by, the elephant hunt. And, like the other hunters, he arrives in camp totally exhausted every evening. It is not only the mountains that are draining the hunters, they also have four hours of jarring driving to tackle on a daily basis, to and from Mashambanzhou on a very primitive road. As the hunt progresses, it takes its toll. The hunters see a great deal of elephant bull sign in the mountains, and they follow and approach a number of these bulls, though none make the grade. Up until the tenth day that is. On the tenth day the client takes a grand elephant bull with a splendid brain shot after a long follow up through the mountains. When the hunters arrive in camp late that night, all fatigue is forgotten and the celebrations last until the early hours. Both professional hunters are of the opinion that the bull will go sixty pounds or more, but we shall find out for certain the next day when we recover the ivory. This visiting hunter, like the vast majority of those that hunt Chewore, is a most satisfied customer. Around the flickering campfire with bourbon and cigar clutched close. The following morning it is my turn to head off well before dawn, Mashambanzhou bound. Dean accompanies me, as does December and three other guys, including a capable skinner who shall have his work cut out for him on this day! It is my maiden journey to these mountains and I am excited at the prospect, although I understand that it is an extreme physical challenge that faces us. My excitement is fuelled mainly by the fact that we are going into completely untouched land – untouched and totally removed. I also have an unspoken wish to see some sign of a Vadoma honey gatherer, though I know that the chances of this are highly unlikely. I have heard many stories about the Vadoma people and have become fascinated by these stories. The Vadoma are a small and lost tribe of hunter/gatherers that have been displaced from their historical hunting grounds (Mashambanzhou and the adjoining Mkanga Valley) by the government, and resettled in Dande Communal Land. The logic behind displacing the Vadoma is that they needed to be ‘civilized’. For the life of me, I cannot figure out how barbarians can civilize other men. Anyhow, the majority of the Vadoma have assimilated with other valley dwellers now, but not all. A few of the old mdalas have found it impossible to integrate and continue to lead the only life they know. Living as they have done forever, where they have lived forever, in the mighty Mashambanzhou Mountains. Although these old hunters are considered to be poachers by the so-called authorities, we don’t consider them to be. In any case, it doesn’t make a difference who does and doesn’t consider them poachers. Nobody, authority or otherwise, will ever find a Vadoma in the bush, should that Vadoma not wish to be found. These old Vadoma hunters are the world’s most proficient bush-men, even more adept than the animals they hunt. Another issue of interest pertaining to the Vadoma people is that a number of them have two toed feet, similar in a way to the feet of an ostrich. This genetic curiosity should be of great interest to anthropology. We do not however, come across too many anthropologists in Chewore. And even if we did, those anthropologists wouldn’t stand a snowball’s chance in the Mashambanzhou Mountains of ever finding a Vadoma. Anyway, one of my most recent endeavours has been to learn as much as I possibly can about these intriguing old hunters, and to try and somehow find one and talk with him, for educational purposes. Our task on this day is to locate the elephant carcass, remove the ivory and return with it. The client also wishes us to secure a reasonable amount of belly skin, in order to make soft gun cases for his favourite weapons. When hunting is in progress, recovery (particularly of elephant and buffalo) takes up much of my time. It is a duty that constitutes a relevant percentage of any gopher’s time. Generally speaking, recovery is an extreme physical challenge, involving backbreaking work over harsh terrain. I revel in it, as does my main man December. On most recoveries, we recover everything from a particular animal. And by everything I mean everything, besides elephant bones and offal that is. On this particular occasion however, we are going to recover very little of the elephant in question, only the tusks and some belly skin. One would need to understand the geography in order to appreciate why. It is obviously impossible to get a vehicle anywhere remotely close to the elephant carcass, being deep in the heart of the Mashambanzhou and all, and carrying out anything more than the absolute necessary is out of the question. Two hours later we are at the base of the mighty mountain range towering high above, in the shadow of extreme intimidation. I do not forget that ascent of Mashambanzhou in a hurry. The slope we climb is not too shy of vertical and it is not long before energy levels are seriously depleted, sweat flowing freely. Initially there is a bit of chitchat between the guys as we climb, but that soon dries up, replaced by heavy breathing. As we climb ever higher, the heavy breathing becomes heavy panting and eventually, as we near the crest, light whimpering. Leg muscles are tested to the extreme as we climb determinedly, higher and higher up the mountainside. Dean is leading the way because he is the guide, having come this way several times before in the past week. Added to which Dean just likes leading, which is good for he is an able leader. I am second in line with December close behind, followed by the other three porters. About three quarters of the way up, I begin to take strain, struggling to hide that strain. Dean is a very fit and strong individual and I have been keeping pace with him the whole way. I dare not slow up or rest because December follows closely behind and I know that he will not flag, or have much patience with flaggers. The three guys bringing up the rear have already flagged and are strung out far below – conspicuous overall clad flags, struggling along on the rock-strewn mountainside. As we approach the summit, my hands touch ground as often as my feet – it is now extremely steep. Occasionally someone loses purchase and slides backwards a metre or two, dislodging stones and grasping frantically, before clutching scrub or wedging himself against the person behind. Thankfully none of the backward slides turn into a full-blown human slide! A couple of hours later, with legs burning as never before and robotically hauling myself over the last few metres in the hand and footprints of Dean McGregor, I reach the summit of Mashambanzhou for the first time. And I lie down flat on my back, spread-eagled on the mountain. We spend another twenty minutes or so waiting for the three struggling porters and enjoying an incredible view of the Zambezi Valley. Slightly offset from the Mashambanzhou Range, stands the imposing and isolated flat-topped sentinel that is Chiramba Kadoma Mountain. Chiramba Kadoma literally means ‘to refuse people’, and in the Vadoma culture it is forbidden to approach that mountain. It is said that anyone who dares to challenge the mountain should be prepared to reap the whirlwind. After allowing the porters time to regain their breath, and chatting a little about the legend of Chiramba Kadoma, we move off into the range, the trial is far from over. The elephant was shot some distance from where we now are, and many ups and downs still separate us from that place. Two more exhausting hours ensue before the vultures lead us in to the carcass and we are able to take another rest. Water is strictly rationed, we shall spend most of the day here and we have brought along only enough and no more. Once everyone has rested and drunk a little, work begins on the carcass. The skinner has soon skinned out a satisfactory wedge of belly skin and begun work on the ivory, whilst the rest of us hover around and watch. As far as chopping out the tusks is concerned, there is not much for anyone to do, except watch the skinner and his assistant. Chopping out ivory is precision work without room for any error. If the utmost care is not taken, the tusks could be irreparably damaged and nobody wants that to happen. In any case, we have a highly experienced skinner with us and he is not likely to err. Dean and I soon become bored watching the skinner chopping and we decide to walk around a bit, to look the unfamiliar country over. We walk a little further into the mountains and the chopping gradually fades. In due course, we descend yet another incline and come upon a little winding mountain river, hidden by bush in the valley below. There is actually not much to hide for this is a tiny river, the sand bed only a couple of metres across. Dean walks upstream whilst I walk down, just to have a look. Presently I am brought up short by a shout from Deano, now some distance away and hidden from view. “Hey Dave, come and have a look at this! Dave, come quickly!†“I’m coming,†I yell, wondering what on earth he could have discovered? He certainly sounds excited. It could be anything in fact, this guy could find a snowball in the Mashambanzhou – such is his inquisitive and adventurous nature. “Dave, come quick!†‘He’s probably found something totally irrelevant,’ I think, as I trudge tiredly through the heavy sand and heat. ‘Probably a grasshopper that he’s never seen before, or something.’ I round a bend and there is Dean, crouched down in the sand, totally absorbed by what he crouches over. Seconds later, fatigue is forgotten and I become more excited than him, if possible. Dean has discovered the biggest elephant tusk that either of us has ever seen, lying there exposed on the sand of that little mountain chikowa, literally in the middle of nowhere. In fact this place is beyond nowhere, nowhere being considerably closer to home. Anyhow, lying there on the sand is the biggest elephant tusk either of us has ever seen, and we are extremely excited indeed. It may not seem like a big deal to others, but for us it is a most momentous moment. I spend my nights dreaming of moments like these. After the initial shock has worn off, expletives expended, I whisper the question that many would ask. “Do you think it’s a hundred pounds?†Dean continues staring down at the tusk, stretching out a hand and touching its element-corroded surface with raw reverence. Then, still crouched, he shuffles closer and lifts the tusk slightly off the sand, cradling it in his two powerful hands, evaluating its weight thoughtfully. It is a very heavy tusk and even this strong man feels it. Dean lowers the tusk, before standing. “I don’t know for sure Dave, but it’s very close to a hundred pounds.†“Holy smoke!†I exclaim. I don’t really say holy smoke, but this story has been censored to protect the innocent. And there, standing in awe over that huge tusk, I remember the words of the mudzimu that day on the banks of the Angwa River. “The heavy ivory is in the mountains.†After a tad more scouting about, we find the big tusk’s partner close by, also lying on the sand, slightly upstream. This tusk is broken off at the base and is not nearly as large, Dean reckons about sixty pounds. Still, large enough. It is a most strange discovery for we find nothing else, no other sign that an elephant died here. No bones at all, just the two tusks lying exposed on the riverbed. Bearing in mind that these tusks have been lying here for a very long time, the corrosion suggesting years and years. Anyway, we don’t have too much time to reflect on the why and how of it all, now we have a serious predicament on our hands. There is absolutely no way we are going to leave these tusks here, but we have an obvious manpower deficit. After all, we had only expected to carry out two tusks and some belly skin when the recovery was planned the night before. There are six men to carry four big tusks, a belly skin, rifle and rucksack – containing knives, water and a few other items. I am not too concerned about the axes for those can be chucked. Still, it is going to be problematic. There is too much weight and there are too few of us to handle that weight. We carry the tusks back to the guys at the elephant carcass. Dean is the biggest so naturally he carries the biggest tusk. Even the short distance back to the carcass is a major exertion for me, and I must be carrying about thirty pounds less than Dean. I realize that we are now facing an extreme challenge. To get all of this ivory out of the mountains is going to take serious strength and tenacity, and I don’t know if we have enough of either. It is already noon. Four guys will carry tusks and one the belly skin – Dean has his rifle and the rucksack. A particularly scrawny porter is chosen to carry the belly skin, which is considerably lighter than the lightest tusk, and the rest of us are tusk bearers. There is only one man amongst us that could possibly handle the big tusk and that is December. December does not have to be asked, he expects it of himself. The other two guys and I each select, and take up position beside, one of the three smaller tusks. For sentimental reasons, I select the big tusk’s corroded partner. With Dean leading the way out of the mountains, we make the effort. A short while and a lot of sweat later, I am seriously regretting our earlier discovery. Carrying an elephant tusk is very uncomfortable. A tusk is shaped in such a fashion that one never seems to have it suitably shoulder balanced. Shoulders take serious strain when carrying ivory, and obviously the heavier the ivory the more severe the strain. The strain is also dependant on the strength and durability of the carrier of course and, therefore, December is probably experiencing the same degree of strain as the rest of us, including the scrawny fellow with the relatively lightweight belly skin. December is a machine. As Dean suggested, the big tusk is close to one hundred pounds, a tremendous weight indeed. Of course, December does not carry it easily, but he carries it competently – up and over and down the other side, never walking flat ground. Yes, December is a machine. I am not a machine and the big tusk’s smaller partner is fast doing me in. I begin stopping occasionally to change shoulders, which is a bad sign. But I have no choice because both of my shoulders are on fire and need to be rested periodically. The more one shoulder is rested, the more it needs to be. I gradually grow weaker and we have not really even begun. Thankfully I note that the other tusk bearers are also feeling it, and that I am not necessarily going to lose too much face. December and I are bringing up the rear but I sense that that will soon change – there is an increasing amount of groaning and cursing coming from up ahead. After a time we progress somewhat, albeit painfully, and a shout from the front lets us know that we are not too far from the place we begin descending. I am relieved although I know that the descent is going to be a nightmare. And then a six-inch thorn pierces straight through my shoe and deep into the sole of my foot and I go down heavily. I yelp and collapse to the ground, dropping my tusk and bringing the others to a concerned halt. December turns to me. “Chi cha netsa?†“What’s wrong?†“Minswa.†“Thorn,†I gasp, through gritted teeth. Sitting in the dust cradling my foot, I tell the others to carry on. “I’ll catch up soon,†I say. “It’s no big deal and December will wait with me.†It actually is quite a big deal, agony in fact, but I don’t want anyone to see my moist eyes. Avoiding eye contact, I begin unlacing my shoe as the others continue off down the trail. December lowers the big tusk to the ground and walks over. My shoe is filled and the blood is still pumping from my skewered foot. I wince as December takes my foot in his hands to assess the damage. “It is deep and it will be painful, but it shall heal soon. For now there is nothing to do but staunch the blood flow with earth and tie your shoelaces extra tightly. It is getting late now.†I look up at the sun and realize that it must be 3 pm already. My foot is throbbing and I don’t know how I will continue, but I know that December is right. There is nothing much else to do but put my shoe on and plod on. December and I are alone, bringing up the rear. December is strong and carrying the big tusk straight-backed and patiently, whilst I hobble along painfully in front of him. December does not ask how I am getting on – there would be no point for he sees that I struggle. We are walking a crest with an almost sheer cliff dropping away on our right, down to the valley floor far below. Although the valley floor is directly below us now, we still have a distance to cover before we reach the path that leads down to it. Occasionally, when the terrain allows, we catch a glimpse of Dean and the other guys walking the ridge some way in front. Exhausted and in pain I stop and offload my tusk. “There is a distance to cover yet, I will not make it,†I say. “You shall make it,†says December, lowering the big tusk to the ground. “You have no choice.†“Carrying this ivory down that klipspringer track shall be no small undertaking,†I say, standing like a poised hammerkop* on one foot, whilst resting the wounded one. “Yes,†agrees December, “the worst is yet to come.†I hobble to the cliff edge and peer over at the valley floor hundreds of metres below. ‘So near yet so far,’ I think, and with that thought the solution hits me. I turn to December, a huge grin replacing my pained expression. December knows what I am thinking and he shakes his head slowly. * Predominantly poised fishing bird. “It is too dangerous,†he says. “We shall reach the vehicle in no time,†I counter. “Well before the others, let us do it!†December shakes his head mournfully from side to side but my mind is made up, and he knows it. We are getting to know each other very well, December and I. “It is too dangerous,†repeats December, but I have already lifted my tusk and am walking over to the cliff edge. Without pausing in my stride I step off the edge. December follows shortly afterwards. When I say the cliff face is almost sheer, I mean that it is probably 50 degrees or so – sheer enough anyway. It is obviously far too steep to keep one’s footing for even a short distance. This is nothing other than freefall cliff tobogganing, Chewore style! Tobogganing down the Mashambanzhou astride an elephant tusk certainly proves to be a most unique experience indeed. ‘Well,’ I think, as we hurtle down the slope, gathering momentum and crashing past brush and stunted mountain trees along the way, ‘the tusks are seriously corroded anyway!’ Fortunately neither of us is carrying the client’s tusks, especially since he is a difficult guy and all. Of course, December and I don’t maintain silence as we fly down the slope, we scream. Adrenalin pumps and pain is forgotten as we attempt influencing our flight path by shifting weight this side and that. Skateboarding without wheels and, I should imagine, with a great deal less control than the average skateboarder has. From far above I hear yodels, as the other guys witness our crazy descent of Mashambanzhou. I take them to be yodels of encouragement for we seem to be making good progress. December and his tusk are heavier than my tusk and I, and he has caught up, bumping me repeatedly from behind. It is reassuring bumping and I shift up and bomb on, gravity fed down the mountainside. I lose my tusk several times, as does December, but somehow we always seem to reattach ourselves. Using feet as fairly ineffective brakes, and either buttocks or tusk as body-board, we approach the valley floor at horrific speed. A short time later we are consolidating, dusting off and laughing uncontrollably down in the valley, not far from the vehicle at all now. Our madcap descent has certainly achieved its purpose and we have reduced the toil factor considerably. An added bonus is that our injuries are almost nonexistent, only minor bruises and abrasions. Fortune favours the stupid, as we like to say in Chewore. Before carrying the tusks the last couple of kilometres to the truck, we decide to go and wash off in a nearby spring that we know of, the rest of the team will take time to arrive. Whilst we are kneeling beside the muddy pool, cleaning wounds and still laughing at our daring, I look down and notice a human footprint, outlined faintly in the ground by the water’s edge. My laughter fades. “December, someone else has been here recently. Someone who does not wear shoes, and someone who has a strangely shaped foot.†December walks over and crouches down beside me, before quietly saying one word. “Vadoma.†Eventually we all arrive at the Land Cruiser – totally exhausted. Adrenalin has been expended and pain is returning. I am looking forward to camp, a hot shower and showing off our incredible discovery. But first we have to deal with the inevitable wheel punctures. The days are decidedly long in Chewore. The large tusk weighs 89 pounds and the smaller one 58 – remarkable discoveries both. Those in the know assure me that, when the big tusk was on the elephant, it would have gone at least a hundred pounds. Both tusks have lost significant weight to time and the elements. Of course, there are many theories as to how those tusks came to be up there in the mountains, lying on the sand in that little chikowa. The theory that makes the most sense to me is that the elephant was poached years before, and the tusks buried in the sand for later collection. Even two strong poachers would have been intimidated by the prospect of carrying those tusks out. This would also explain the baseless smaller tusk – chopping out ivory is an intricate task that cannot be rushed. Obviously we have to hand the ivory over to National Parks and, when we do, I beg them to let us keep the tusks for sentimental reasons. After all, they are damaged and of little commercial value. Parks agree, at US$250 a kilogram. I scratch around in my head a little, but quickly realize that I won’t be able to come up with the US$20 000 or so required – very difficult on a gopher’s budget. All that Dean McGregor, December and I have of that remarkable discovery are a couple of poor quality photos. And great memories of course. Since that adventure, I have returned several times to the Mashambanzhou, always I keep my eyes open for sign of Vadoma honey gatherers. Although I have chanced on spoor again, and have since spoken with several ‘modernized’ Vadoma at their new homeland in Dande, never yet have I come across one of the old timers going about in the mountains. But I know that some still operate there, reluctant to become what they are not. The law considers the few that still live this life of old to be poachers, but I understand otherwise. After all, the mountains belong to the Vadoma, and to big elephant bulls. | ||

|

| One of Us |

I'm sorry, it didn't post very well. I lost all italics and the chapter header sketch didn't go through. I don't really know how to work it out but shall keep trying. I'm sure you'll get the gist anyway. | |||

|

| One of Us |

Sorry, not great pictures, but the best I could do for now.... [URL=  ][IMG] ][IMG] | |||

|

| One of Us |

Where's the book available? | |||

|

| One of Us |

From a guy called Bryan Patton, in Plano, Texas. email: bryan@africanhuntermagazines.com phone:877-261-4226 Thank you for your interest. | |||

|

One of Us |

David, This was a wonderful read which harkens to a time seemingly long past. What makes it more special is that it is not of many decades ago, but still possible to find that undiscovered adventure. Once again thank you.  Member NRA, SCI- Life #358 28+ years now! DRSS, double owner-shooter since 1983, O/U .30-06 Browning Continental set. | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Hunting

Hunting  African Big Game Hunting

African Big Game Hunting  Witchdoctors, Vadomas and Elephant Bulls. Pictures added

Witchdoctors, Vadomas and Elephant Bulls. Pictures added

Visit our on-line store for AR Memorabilia