26 January 2009, 19:06

fla3006Alvin Linden

Hidden Places: Self-Described 'Gun Butcher' Was Artist

Nov. 24, 2007

He called himself a “gun butcher” but to the rest of the world, he was an artist.

Alvin Linden made gun stocks—the wooden portion of the rifle or shotgun that the unknowing identify as more ornamental than business—and he made them with a style and craftsmanship that has been unmatched since his death at the age of 60 in 1946.

He was world famous and hobnobbed with kings and princes. He was the focus of magazine articles and accolades from fellow craftsmen and admirers. But, due to a crippling injury, he rarely left his modest workshop, cluttered with a surprisingly primitive array of axes and chisels located just north of Bryant.

The dilapidated shop is still there, concealed in the brush, and Mr. Linden’s fame remains real as well—for those willing to do a little digging.

“It can be said that he was to gun stocks what Antonio Stradivari was to violins,” Ludwig Olson wrote in an article published in Outdoor Life’s 1987 “Guns and Shooting Yearbook.”

Gary Strasser, a premier shooter, collector, international big game hunter and hunting consultant, said Mr. Linden was simply unmatched at his artistry.

“He always said he would take a piece of wood and chop off everything that didn’t look like a gun stock,” Mr. Strasser said. “He was world famous, a true artist of his time.

“This was in the days before pantomime machines which make an exact copy,” Mr. Strasser continued. “His gun stocks would snap into place perfectly. They don’t even do that now.”

(A confession: Like most in the northwoods, the crew has a passing knowledge of rifles and shotguns. But we were totally unaware of the world of collecting and the intricacies of fine gunsmithing. This is new territory.)

Mr. Linden was born in Sweden in 1886, where he learned cabinetmaking from his father. The family moved to the United States in 1899 where father and son worked at the Pullman Palace Car Company, also known as the Pullman Works, in Illinois, finishing interiors of sleepers, diners and private railroad cars.

Mr. Linden wrote that he developed his love for guns after his father gave him strict orders never to have anything to do with them.

“Being bull-headed, it was only natural that I would do just the opposite,” he said. “While still very young, I got a hatchet and a pocketknife for Christmas. My father told me how to chop my fingers, not how to avoid it. So I didn’t chop my fingers and have not done so since.”

According to his obituary published in the July 5, 1946 Antigo Daily Journal, Mr. Linden came north in about 1906, worked as a logger for a time and eventually took up the trade for which he became famous, fashioning gun stocks. He lived with his sister and brother-in-law, Dan and Ellen Grant on their Bryant farm, working in his small frame shop near the house.

“For most of his life Mr. Linden suffered from a severe physical handicap that partly crippled him, but this seemed only to intensify this ambition to excel in his profession,” his obituary noted. “Seldom able to leave his home for long, his life was never the less rich in associations with men who shared his interests and enthusiasms and sought him out because of his wide repute.”

The accident happened in about 1907 when he backed into the stub of a limb while sawing wood, injuring his spine. Arthritis developed, causing difficulty in walking and greatly impairing the use of his left arm. He also had trouble sitting for long periods of time, making long-distance travel nearly impossible.

So his work came to him, via parcels regularly delivered by postal carriers. Those packages arrived from gun enthusiasts from across the world, including European and South American royalty.

Mr. Strasser recalled that his father, Leland, who knew Mr. Linden well, saved the stamps from those envelopes and amassed quite a collection.

To understand Mr., Linden’s allure requires some knowledge of firearms. As Mr. Strasser explained, the business-end of the gun—the barrel and firing mechanism—must fit snugly into a well-made stock in order for the weapon to perform accurately.

“If it’s not made properly, the gun won’t shoot straight,” he said. “It’s a very important function of the firearm.”

Simply put—a shoddy stock leads to poor marksmanship.

When asked how tightly the wood should fit the metal parts, Mr. Linden is said to have replied, “as tight as the rear of a steer in fly time.”

Beauty plays a role as well, although some gunbugs may discount the notion. Mr. Linden’s stock had an unmatched elegance, with the cheekpiece flowing forward gracefully to blend into the stock of the pistol grip. Developed with Herbert Dunton, an artist from the West, it was called “harmonious in mass and line.”

Mr. Linden doubtlessly learned many of his skills at his father’s knee, making cabinets. He studied the methods of others as well, including Ludwig Wundhammer, a Los Angeles gunsmith, and Colonel Townsend Whelen. And certainly master gunsmith Ulrich Vosmek of Antigo had an influence on the design and production of his stocks. Mr. Vosmek, who died in 1936, made many a barreled action that Mr. Linden stocked.

(An aside here: Oh, to have one of those firearms today.)

“He had an eye for beauty, and claimed that anyone who could appreciate the lines of a Petty girl (sexy paintings of curvaceous girls by an artist named Petty, whose work was very popular in those days) was fully qualified to lay out and model any curves required on a stock,” Mr. Olson wrote in the Outdoor Life article.

The stock-maker favored walnut, especially the French variety, but also worked in mahogany, maple, cherry and myrtle. He insisted on a straight wood grain running slightly upward toward the front of the weapon to provide strength and minimize warping.

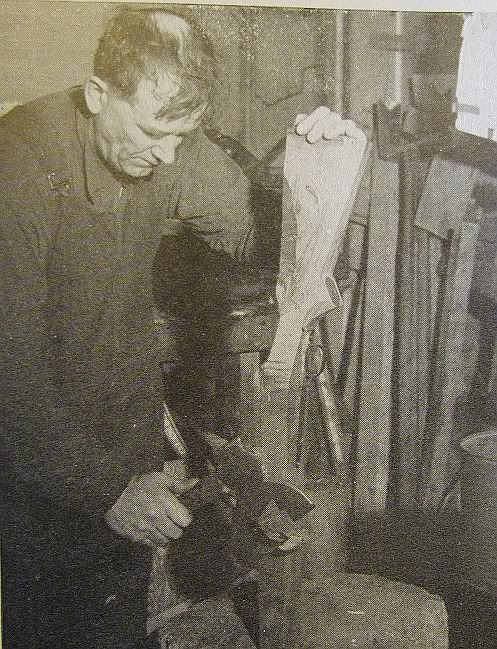

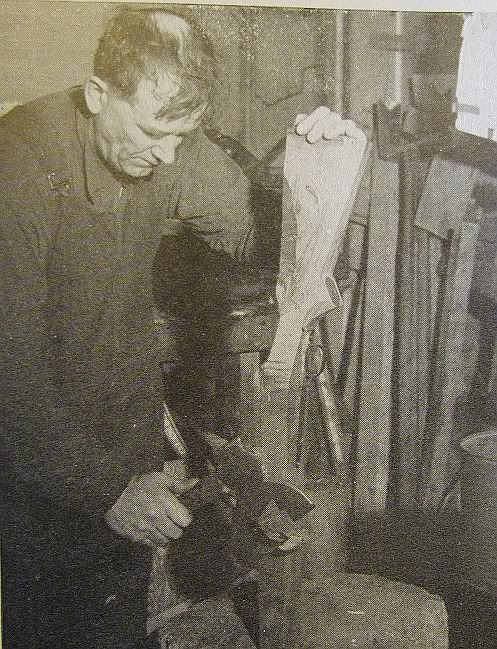

Most of the stock was carved with a sharp hand ax, sending wood chips flying. Instead of using sandpaper to achieve a smooth finish, Mr. Linden raised the grain with water and then removed the “whiskers” with fine steel wool, repeating the process several times. He said sandpaper only pressed the whiskers down, rather than cutting them off.

Mr. Linden also developed his own special finish for his stocks, a mix of linseed oil and spar varnish. And he was renowned for his skill at checking or checkering stocks, creating elegant diamond-shaped patterns without borders across extensive areas of the grip and forearm. Most were simple, but Mr. Linden also became famous for his mastery of the fleur-de-lis pattern.

Buried in Bent Cemetery, the lifelong bachelor is survived today only by rather distant kinfolk. Jody Jones, the wife of Mr. Linden’s nephew, Milton, has been known to put flowers on the graves now and again and there is a niece, Eleanor Jacobson, who lives in Chicago.

Mr. Linden is also survived by legions of gun collectors, many of whom treasure his “Restocking a Rifle,” an all-in-one volume re-issue of his three instruction guides. The book, now out-of-print, includes Mr. Linden’s sketches and photographs of him at work.

Today Mr. Linden’s little workshop sits empty and abandoned, although private gun collections contain examples of his work, many worth upwards of $10,000 or more. His shooting table, where he tested the accuracy of his guns and craftsmanship, has tumbled over and is rotting in the woods. The one-time range is overgrown with brush and the backstops for his targets are moldering into the moss that covers the forest floor.

But the old homestead still has life—as a hunting camp—although it is unlikely the sportsmen who use it are aware of its storied past. And this week at least, the sounds of firearms are once again common in the air around Bryant.

Alvin would feel right at home.

(Hidden Places is a weekly Antigo Daily Journal feature that examines some of the more unusual, unknown and just plain interesting people and places in and around Langlade County and occasionally further afield. The crew is always looking for ideas and gracious guides. Call Lisa or Debbie at 623-4191 or e-mail hiddenplacescrew@hotmail.com.)

28 January 2009, 03:03

astiI`ve made two riflestocks out of blanks. Using electric tools (an overhand cutter? Is it what they are called..) only for taking out wood for the receiver. The rest, I made "by hand". I didnt dare use the axe,, but the man who taught me stockmaking did.

After spending a hundred hours or so on my precious piece of wood, he lost patience and said; let me have a go at it!

I told him, with a sharp voice, that if he messed it up, we would no longer be friends...

I couldnt watch as the blade cut the wood for the first time, but after a while, I just stood there, stunned.

He almost does finishes with his axe, that I barely master with the knife, a true master he is, the 80-yearold man.

Unfortunately, I believe he is one of the last that you can truely call an artist.

There are not many, but I`ve seen on this forum and other forums, that some are still around and I respect these men/women from my heart.

True craftmanship makes great rifles with a soul and a story you never find in massproduced ones.