The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Other Topics

Other Topics  Aviation

Aviation  40 minute parachute ride

40 minute parachute rideGo  | New  | Find  | Notify  | Tools  | Reply  |  |

| One of Us |

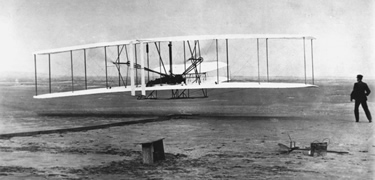

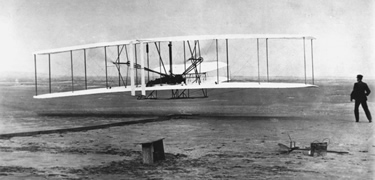

A Routine Mission… In July of 1959, the 38-year-old Colonel William Rankin was asked to give Navy Lieutenant Herbert Nolan a high-altitude navigation checkout in the single-seat F8U Crusader. The plan was to fly in separate orange and silver Crusaders northwards from Beaufort, South Carolina, to Weymouth Naval Air Station, Massachusetts, and back.F8U diagram The north-bound portion of the formation flight that Saturday - July 25th - was in beautiful weather, making for an uneventful journey. However, upon arrival to Weymouth, Nolan felt that his plane’s radio was giving him trouble. A line mechanic checked the set, and assessed that it was not going to be a simple fix, so the pair remained overnight as the technician repaired the vexsome comm setup. The following afternoon, on Sunday, July 26th 1959, Rankin and Nolan consulted with the base meteorologist about the weather expectations for their return flight. The briefer warned the duo of the possibility of thunderstorms and cumulonimbus clouds between 30,000 and 40,000 feet in tops in southern Virginia, but, otherwise, an ordinary flight was to be anticipated. Rankin asked, “Well, since I can go to 50,000 feet if necessary that won’t bother me. I can get over this weather with ease. Any frontal conditions?” “Negative, colonel,” replied the briefer. “The weather is strictly of the isolated thunderstorm variety.” Figuring that – if any storms were encountered – they could just climb over them, they filed VFR flight plans for 44,000 feet, at an airspeed of 540 mph. They figured they would be back in South Carolina some 70 minutes after takeoff. A Flight of Two… After a series of preflight system and instrument checks, the pair took off. Rankin’s Crusader, naval bureau number 143696, was assigned to the Headquarters and Maintenance Squadron 32 (H&MS-32) but he used his old squadron call sign, “Tiger One,” and Nolan used “Tiger Two.” Leaving New England, the flight proceeded as predicted - a perfect flight in perfect weather. That was, until they approached Norfolk, Virginia. There, Rankin noticed the “dark, massive rolling clouds of a thunderstorm” looming on the horizon. Opting to climb over the 45,000-foot-tall mass, he and Nolan leveled off at 48,000-foot mark, and turned past the Norfolk radio beacon. He checked the time – a few minutes to 6 – and started to relax, while quietly rehearsing the familiar arrival into Beaufort in his head. A glance to his instrument panel showed that his engine was showing a slight power loss and, having lost some altitude, he proceeded to climb back to his previous flight level. But as the plane passed through 47,000 feet at an airspeed of Mach 0.82, Rankin heard a loud thump, and a rumbling sound begun to growl from his only engine. At nine miles above the earth’s surface, the red ‘FIRE’ warning light illuminated. Instinctively, he quickly retarded the engine throttle. There was a problem with his only engine! He quickly radioed Nolan, "Tiger Two, this is Tiger One. I am having engine trouble – stand by. I might have to eject.” F8U adNolan responded: “Roger, Tiger One. If you have to go, let me know,” as Rankin’s warning light dimmed. The power reduction seemed to be working. But then, the needle of the tachometer rapidly tumbled to zero in the sunlit silence. This wasn’t a simple jet flame-out – the engine must have seized! Rankin pulled a lever in his cockpit to deploy an auxiliary power turbine – which would maintain the plane’s electrical & hydraulic control systems - but the lever broke off in his hands. "I had no power, radio, instruments or control over the plane," Rankin later recalled. "I had to get out fast. Otherwise speed would build up and I'd never survive ejection from the craft." As the Crusader continued to climb, but slow, above the clouds, Rankin quickly weighed his options: he could try to let the plane descend, but as it would accelerate, it risked entering into a spin which, with no control of the plane, would be unrecoverable and make ejection near-suicidal. Only wearing his helmet and his blue, lightweight, flight suit, and despite an outside temperature of −70°, at 6:00pm, Rankin squared his shoulders, tighten his straps, and muttered to himself, "This is going to be a pretty high one.” He had made his decision – to eject! In accordance with his training, he pulled the two overhead handles on his seat, triggering the ejection sequence. Instantly, a canvas windscreen came down over his face, and an explosive charge propelled the plane’s seat, with Rankin strapped aboard, through the plastic canopy, and away from the crippled Crusader. Artist's concept of Rankin's ejectionInto the Atmosphere… Then, a cable from the plane yanked the metal seat off Rankin’s posterior, leaving him with nothing more than his helmet, oxygen mask assembly, and parachute, which was preset to open automatically at 10,000 feet. The sudden rush of air stripped Rankin’s left glove from his hand. But that was merely the beginning of his long, lonely, fall to earth... "I had a terrible feeling like my abdomen was bloated twice its size. My nose seemed to explode. For 30 seconds - I thought the decompression had me," recounted Rankin in his memiors. "It was a shocking cold all over. My ankles and wrists began to burn as though somebody had put Dry Ice on my skin. My left hand went numb.” Within seconds, his extremities became frostbit, and the sudden decompression caused him to bleed from his eyes, ears, nose, and mouth, causing, “my eyes felt as though they were being ripped from their sockets, my head as if it were splitting into several parts, my ears bursting inside.” Despite the merciless assault on his tumbling body, he was conscious, even as the pain permeated every inch of his stocky frame in the bitter cold. Owing to his training, he managed to quickly find his oxygen mask and its five-minute supply of air, but allowed himself to continue to free fall. "It seemed like I free-fell an eternity,” Rankin recalled. “All this time I had this keen desire to pull the ripcord. I had to keep telling myself, 'If you do, you'll slow down and freeze to death or die from lack of oxygen.' Just as I was considering pulling the cord, I felt a shock.” While still in the upper regions of the thunderstorm, with near-zero visibility, the parachute opened. “I looked up to see the chute. All I could see was cloud. But I could tell from pulling on the risers that I had a good chute.” He quickly calculated that, assuming a reasonable descent rate of a thousand feet per minute, he would be on the ground in ten minutes. However, the bellowing storm clouds had something else in mind for the planeless pilot. His parachute was gradually forced upwards by warm, rising winds. “I saw that I was in an angry ocean of boiling clouds, blacks and grays and whites, spilling over each other, into each other, digesting each other. I became a veritable molecule trapped in the thermal pattern of nature’s heat engine. I was buffeted in all directions—up, down, sideways, clockwise, counterclockwise, over and over; I tumbled, spun, and zoomed straight up, straight down, and I was rattled violently, as though a monstrous cat had caught me by the neck… Before long, I found out the storm had allies with whom I had to do battle, physically and mentally: thunder, lightning, hail, and rain. I was afraid I wouldn't make it. It seemed like an eternity." "I'd see lightning. Boy, do I remember that lightning. I never exactly heard the thunder; I felt it. I remember falling through hail, and that worried me; I was afraid the hail would tear the chute. Sometimes I was falling through heavy water—I'd take a breath and breathe in a mouthful of water. Sometimes I had the sensation I was looping the chute. I was blown up and down as much as 6,000 feet at a time. It went on for a long time, like being on a very fast elevator, with strong blasts of compressed air hitting you." At one point, a lightning bolt lit up his parachute canopy, making Rankin believe that he had died. "At one point I got seasick and heaved. I went up and joined the chute. It draped over me like a sheet, and I was afraid that when I blossomed again, I'd be tangled in the shrouds and risers. But I wasn't, thank God.” A Literal Landfall! And he began the approach the ground, more pleasant changes occurred in his environment. “At last, I realized I was getting warmer. The air was smooth. And rain was falling on me. I figured I was down to 300 or 500 feet. I told myself, 'All I have to do now is make a good landing.'" Suddenly, he emerged from the overcast, about 300 feet above the ground, and spotted evergreen trees – it was the first time he had seen the ground since he ejected from the plane. Swept by stiff ground winds, and in the darkness of the storm, Rankin’s chute fouled in the branches of a tall pine tree, and he slammed headfirst into the conifer’s trunk. He disconnected himself from the parachute, as he recalled it, "and the next thing I knew I was on the deck." He embraced the wet loamy soil, and felt the cool wind blow over his battered physique. But the pains of his body compelled him to seek help – the ordeal was not over, yet. Groggily, he arose to his feet - stiff, cold and numb - with his crash helmet knocked askew. Almost hysterical, he stumbled into the surrounding wooden thicket and then, said to himself: You've come this far down for this? Let's get organized. He checked his wristwatch, which read 6:40 pm, figured he had landed at a logging camp, armed himself with his issued survival knife, and he began walking, or as Rankin put it, “having lost a great deal of blood, stumbled more than walked” a procedural square search through the woods. After walking out two ninety-degree turns, he found himself on a dirt country road that took him through a cornfield, and onto a nearby highway. A dozen or so cars passed him as he stood on the road - wet, bloody, stained, and exhausted - waving weakly. He laid down in the road, in an effort to force a motorist to stop, but several just drove around the distressed aeronaut. Good Samaritans… Finally, a small boy, riding with his family’s car on North Carolina State Highway 305, saw Rankin and cried, "Dad! That's a jet pilot. He’s in trouble. Stop. Help him!” The boy’s father, Judson Dunning, slowed the car and stopped for Rankin. Forcefully, Rankin barked to the driver, “Help me. I’m a pilot. I’ve just ejected from an airplane. Take me to a hospital.” Dunning directed him to the front seat of the car. After introductions, the pilot gifted his helmet to the Dunning boys – Charles, Earl, and Jerry - in gratitude for spotting him. Later, the family would retrace Rankin’s mile-long path on the ground, and recover his parachute & survival gear. Unable to drive Rankin to a hospital since they were low on gas, the Dunnings took the disheveled aviator to a country store in Rich Square, North Carolina, where he collapsed on the floor while waiting for an ambulance to carry him to Roanoke-Chowan Hospital in nearby Ahoskie. Once under medical care, he was treated for internal bleeding, broken bones, and frostbite. Crater formed by #696 Rankin’s pilotless Crusader, however, descended low over several homes shortly after 6 pm, and exploded in a pea field, near Coleman's sawmill on State Highway 258, about a half-mile from the town of Scotland Neck - some 20 miles to the south of where he came down. Luckily, no one on the ground was hurt as the disabled jet plowed a 20 foot deep crater as it nearly vaporized in a ball of flame. Sifting the Wreckage… An hour after the crash, rescue crews from Seymour Johnson Air Force Base were at the crash site of #696. Search crews were guided by locals to the wreckage in the darkness – unaware the pilot was successfully rescued. While little debris was recovered, a key piece of evidence to the mishap’s source – a part of an engine-driven fuel pump – proved the jet’s turbines had seized, and later confirmed Rankin’s decision to eject when he did was the best course of action. Rankin in the HospitalThe next day, around noon, Rankin was moved by ambulance to Cherry Point Marine Base in North Carolina, and was later transferred to Beaufort Naval Hospital, where he told reporters that "I'll be back in the air in a month” although he did spend several weeks in the hospital recovering. He was discharged from the hospital in mid-August into a program of outpatient physical rehabilitation. Returning to Duty… As a result of the rapid decompression, doctors tested Rankin in a hypobaric chamber to insure no lasting ill effects from his airborne ordeal. With nothing found, he returned to flight duties, and was later sent to Armed Forces Staff College in Norfolk. While there, Rankin wrote a book about the experience, as well as his career to that point, entitled "The Man Who Rode the Thunder" which was published by Prentice Hall in 1961. His experiences have also been recounted in numerous books on aviation and weather phenomenon. According to the Naval Aviation Safety Center, Rankin holds the distinction of having survived the longest parachute descent in history – over 40 minutes. He retired from the Marine Corps in 1964, appeared once on “The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson” in March of 1971, and continued to live a quiet life until he passed away on July 6, 2009 at the age of 89. | ||

|

One of Us |

Great post! 577 BME 3"500 KILL ALL 358 GREMLIN 404-375 *we band of 45-70ers* (Founder) Single Shot Shooters Society S.S.S.S. (Founder) | |||

|

| Powered by Social Strata |

| Please Wait. Your request is being processed... |

|

The Accurate Reloading Forums

The Accurate Reloading Forums  THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS

THE ACCURATE RELOADING.COM FORUMS  Other Topics

Other Topics  Aviation

Aviation  40 minute parachute ride

40 minute parachute ride

Visit our on-line store for AR Memorabilia